September 18, 2022 On the passing of

Ron Earley: Organ

donation added years

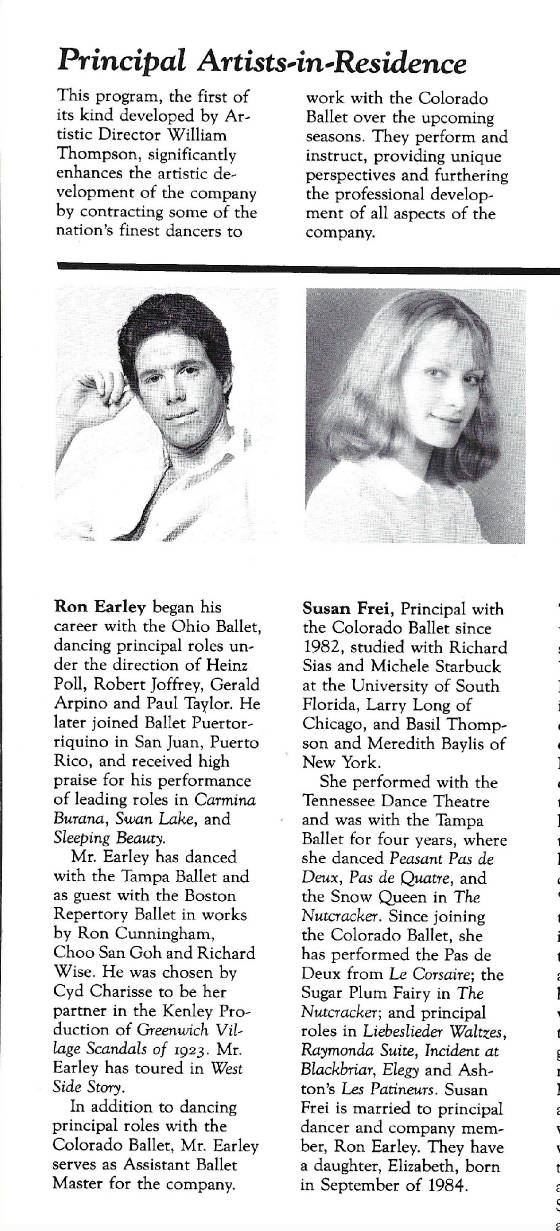

Colorado Ballet program cover, 1985-86 season: Ron Earley and Susan Frei My brother-in-law, Ron Earley, passed away recently in Tulsa. He was 71 years old, but among the stories I want to

tell here is of the years added to his life because someone -- years ago -- signed up to be an organ donor in the case of

tragedy. More on that in a moment, but I'll start with how Ron and my sister, Susan Frei Earley, at times

could seem out of a movie as ballet stars who met while dancing with the Tampa Ballet and often performed as partners there

and with the Denver-based Colorado Ballet. They were married for 39 years and have a daughter, Elizabeth, a Tulsa nurse. Susan now is the rehearsal director and artistic coordinator for the internationally

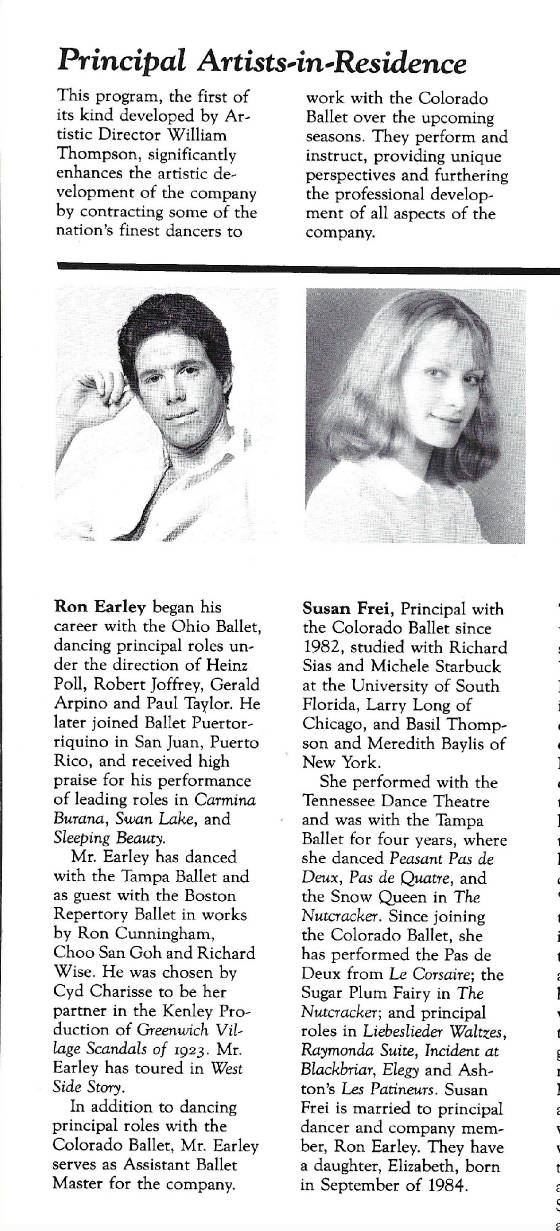

respected Tulsa Ballet, which has drawn its dancers from around the world. Here are Ron and Susan's bios from the Colorado Ballet program for the 1985-86

season.

Now, on to a column I wrote for The Denver Post

in February 1999, tying Ron to the illness of NFL great Walter Payton, who at the time had just been diagnosed with primary

sclerosing cholangitis, a rare liver disease. Payton died eight months later of bile duct cancer. It turned out that he already

was too ill for an organ transplant to work for him, so he never had one, but he spent his final months advocating on behalf

of organ donation programs. As the column details,

Ron also had been diagnosed with primary sclerosing cholangitis in the early 1990s, underwent a liver transplant in Denver

-- and lived more than 30 additional years. So in 1999, our family recognized the commonality of Ron's situation and that

of Payton, in part because my father, Jerry Frei, was the Bears' offensive line coach for three years during Payton's career.

Column

run date: February 25, 1999

Organ donor brings life By Terry

Frei

This is going to be about a small world and big hearts, and I'll start with a visit to Harry Caray's

restaurant in Chicago last week.

My sister, Nancy McCormick, pointed out a note on the bottom of the "specials"

menu. Any customers who took out their drivers' licenses and signed the back, signifying their willingness to participate

in the organ-donor program, would get a free dessert in honor of ailing Walter Payton. "You know,"

Nancy said, "Walter has the same thing Ron did." I had thought so, but until that moment, I wasn't certain. Payton,

the National Football League's all-time leading rusher, has a rare liver disease - primary sclerosing cholangitis. Without

a liver transplant, he probably will die within two years. My father, Jerry, was the Bears' offensive-line coach from 1978-80 before joining

Dan Reeves' staff with the Broncos. Payton was in his prime, and the offensive-line coach was one of his many fans. "He's

one of the finest football players ever made," Jerry Frei said this week. "He could do anything. If you had wanted

him to be a linebacker, he could have been. He blocked, he could have tackled, he could do anything. And he loved playing

the game."

Jerry Frei has something to tell Walter Payton.

"I know somebody who

beat it," he said.

In the 1980s, Ron Earley and his wife - Susan Frei, also my sister - were principal

dancers with the Denver-based Colorado Ballet. If you annually took the kids to "The Nutcracker" or were a regular

ballet patron in those days, you saw Susan and Ron perform, often in lead roles. Ron was versatile, having done a lot of theater

work as well.

In 1983, Ron was told he had primary sclerosing cholangitis. Like Payton, he isn't a drinker,

and this had nothing to do with alcohol.

By 1991, Susan was with the Tulsa Ballet, which had taken over an abandoned elementary

school as its studio and school, and toured extensively with a corps and management that included many Russians.

Ron

was dancing only part-time, and his health problems were becoming acute. Doctors in Tulsa told Ron he would need a liver transplant,

and he came to the University of Colorado Medical Center in May.

In Denver, doctors gave him grave news.

"They said I could live probably six months at most without a transplant, and it wouldn't be much fun," Ron said

this week.

Ron went on "the list" of those needing a transplant. Susan and their young daughter,

Elizabeth, left Tulsa and joined Ron in Denver. He was given a beeper and told the wait could be two days, two months, or

maybe even too long. It wasn't a simple matter of priority, but of blood-type and size-matching of an available organ.

On

June 12, 1991, Ron indeed was summoned to the hospital for a transplant. Again, he was told of the risks. "They told

me anything could happen," he said. "The transplant might not work. I could die on the table. I could reject the

liver and not be able to get another one, and that would be it.

"So you're sitting there, facing

your own mortality. I wanted to grow old with Susan and see Elizabeth grow up, and I didn't know if I would be able to."

My

wife and I were living in Oregon at the time, and we got the updates. Ron had been called to the hospital. Ron had the transplant.

And, miraculously, 10 days later, he was out of the hospital.

Ron knew his liver came from a man who died in an accident,

and where the accident occurred. (It wasn't in Denver.) A year later, Susan was on tour with the Tulsa Ballet and was dancing

in the city where the man had lived. She went to the local library and looked at the newspaper microfilm. It wasn't hard to

figure out the name of the man who was killed.

Ron debated with himself. He didn't want to jar the family, didn't want them

to revisit their grief. But he decided he had something to say, so he sent the family a note.

"I wanted

them to know the responsibility I felt to him because he had helped give me the gift of life," Ron said. "I didn't

hear back, but that's OK, I understand why. I understand how hard it was, what they must have gone through."

The

organ donation program is not a ghoulish circling of vultures. It is an acknowledgement that horrific, unthinkable, heartbreaking

tragedies occur. Life is irretrievable. Organ donation is infinitesimal consolation to the family, perhaps, but it can forestall

another family having to grieve.

Ron went back to school and obtained a teaching certificate. For five years,

he has been teaching fourth grade at Tulsa's Kerr Elementary School. Susan now is the ballet mistress for the Tulsa Ballet,

meaning she choreographs, casts, teaches and dances in a pinch. Elizabeth, their daughter, is a 14-year-old basketball star.

When

Walter Payton disclosed his illness, Ron and Susan saw tape of the news conference that night.

"When he broke

down and started crying, we both did, too," Ron said. "I knew what he was going through. I'm hoping everything works

out for him. I really hope he has a chance. If I had a chance, I'd tell him that they've gotten so good at these transplants,

people are getting out of the hospital so quickly, if he goes through it, he'll think it's a miracle."

If

you're not already listed on your driver's license as an organ donor, there is a line where you sign on the back to become

one.

It doesn't even have to be in Walter Payton's honor. Back to 2022: Sign up to be an organ donor, folks.

|