|

January 9, 2020 On the Colorado Scene Irv Moss and that grin were Colorado Classics. RIP, Irv

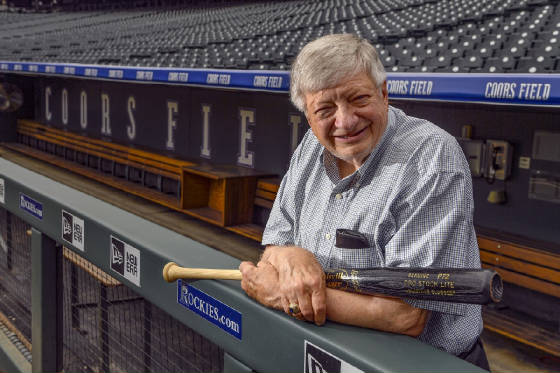

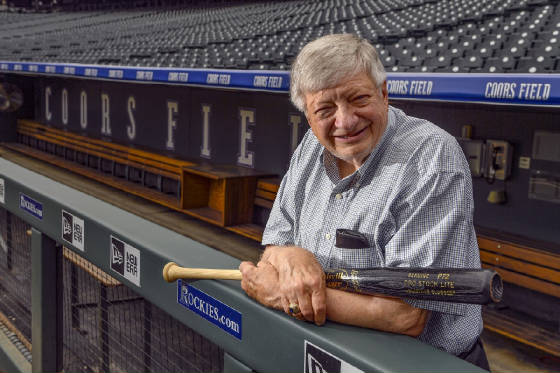

Irv Moss at Coors Field, July 2016

Photo courtesy John

Leyba The call

-- not unexpected -- came from our mutual friend Gary Sever. Longtime Denver Post sports writer Irv Moss, who retired in 2016 after 60 years at

the paper, had passed away Wednesday night. He had been very ill of late, with esophageal cancer. The tributes started pouring in. Irv had this sly grin and the man his older co-workers often affectionately called

by his real first name -- "Homer" -- was good to me from the moment I walked into the newsroom more than 40 years

ago. I know that was the case with so many others. He was a stubborn, prideful professional. And a good man. Rather than go on

here, I can ask you to check out the profile I did of Irv in The Post when he retired in 2016. It's below. I'm proud

to have written it and to have told his story ... at least what I could get out of him. The breadth of his experience mirrors the transformation of Denver as a sports market -- and transformation,

period. I learned a lot writing

that because Irv, well, could be a man of mystery. You knew him. But you didn't. Just one thought along those lines: His long stay at the Post was interrupted by his

1957-60 stint in U.S. Army after he was drafted. (He technically remained a Post employee on military leave.) His time stationed

in Germany overlapped with Elvis'. If you knew Irv, you get that I can say I would not be shocked to learn that Elvis and

Irv were drinking buddies. Because Irv wouldn't have told anybody. July 3, 2016 From copyboy to Colorado Classic, Irv Moss did it all in career that spanned

more than 60 years

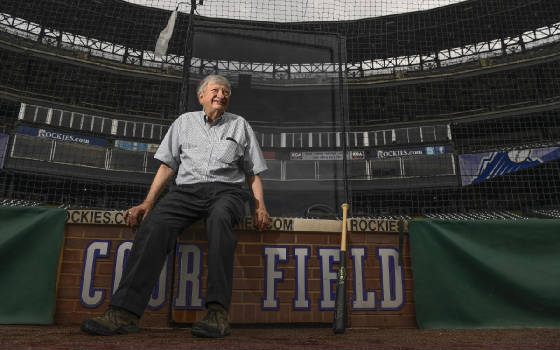

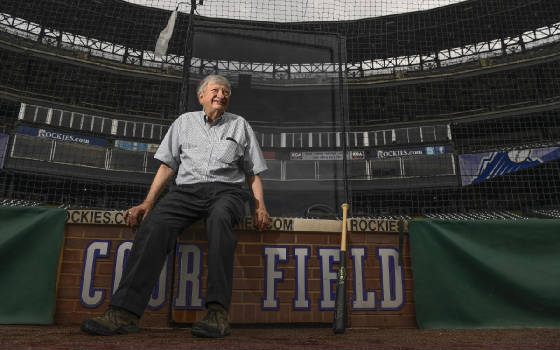

Photo courtesy John Leyba By Terry Frei (Denver Post, 2016) In the spring of 1956, Denver Post sports editor Chuck Garrity was

impressed with the newsroom copyboy’s hustle as he delivered the stock market ticker tape and wire-service copy to various

departments.

Eventually, Garrity asked the young

man: “Do you want to try this?” “This” was sports writing. Sure, Irv Moss said. Garrity assigned Moss to cover the men’s fast-pitch softball

league at City Park, which routinely drew standing-room-only crowds of more than 5,000. If the untried Moss fouled up the

high-profile assignment, Garrity would hear about it. Moss got his story in and in June 1956 became a full-fledged writer in the Post’s

sports department. After a stay of more than 60 years at the Post, Moss’ final day as a full-time reporter was June

24, making him one of the longest serving newspaper employees in the country. “It was an interesting time to watch, and in a way, be part

of the changing of Denver as a sports city,” Moss, 81, said. “When I first started down here, City Park softball

was the big story. And next thing you know, we’re one of the top sports markets in the country.”

Born in Denver, Moss was a 1952 graduate

of West High School. His father, Homer, worked in the garment industry. Irv started out at Colorado A&M in Fort Collins,

but left school when his father became ill. Moss landed the copy boy’s job in early 1953 at the Post, then an afternoon daily

headquartered at 15th and California Streets. He twice left the paper and did some electrician work, but returned to the Post

on Feb. 8, 1956. After Garrity brought him into the sports department, Moss also was part of the Post’s coverage of

the greyhound races at Mile High Kennel Club, the other huge attraction in town at the time, and wrote about high school sports.

“We used to staff the dog races

Wednesday and Saturday nights,” Moss said. “They called it the hot box because that’s when the top dogs

would run.” In 1957, though, he was drafted and entered the Army, joining the 160th Signal Group. He was sent to Boeblingen,

Germany. “I was supposed to be in the signal corps,” Moss said, “but when I got to Germany the place I was

stationed had a pretty good Army baseball team. I ended up the public information person for the team. Stars and Stripes had

an office down in Stuttgart that wasn’t very far away and I’d take stories down to them. So my function was publicizing

sports activities.” Returning to The Post in 1960, Moss dived back into high school coverage. He handed Freddie Steinmark the

Post’s Gold Helmet award in 1966 for his excellence on the football field and in the classroom, and was affected when

the Wheat Ridge star — who played for Texas’ national champions in 1969 — died of cancer in 1971. “The

way that turned out was something you just didn’t forget about,” Moss said. The Broncos had come on the scene in the

1960s, but Moss initially didn’t write much on them. He had moved on from preps and was covering Wyoming football

in 1969 when coach Lloyd Eaton dismissed 14 black players from the team for planning to wear black armbands in a game against

Brigham Young. “They had some great players and it ended their careers and probably disrupted that program for a long

time,” Moss said. Moss covered college football in the fall — Wyoming then Air Force — and then the Denver Rockets

when beat writer Ralph Moore covered golf. The franchise in the new and upstart American Basketball Association was part of

Denver’s baby steps toward big-league status. “We didn’t have anything to compare the ABA to,” Moss said. “I’d

just say it was a lot of fun, with a lot of fun cities.” The Rockets took chartered flights long before it was routine in pro

sports, but the players weren’t completely confident that the planes — from a smaller regional airline —

were first-rate. In the ABA’s second season, in February 1969, Moss traveled with the team on a trip that finished on

Long Island, where the New York Nets played in Commack, N.Y. “On the way to Long Island, they said that a light had come

on that indicated that some generator was not working properly,” Moss recalled. “They told us they’d

have to get that part before we could leave from New York to come back. The word got around that if they couldn’t get

the plane fixed, we’d have to fly back commercial out of New York. “It was so cold in that arena that players on the bench were

sitting in their topcoats. About halftime we got word that they had the part so we were going to have to fly back in that

thing. (Rockets) Larry Jones and Lonnie Wright on their own decided that they weren’t going to come back on that plane

and they were going to pay their way and come back commercially out of New York. “The rest of us got on this plane

and we were going along and you could look out the window and I think the cars on the freeway were going faster than we were.

They had to land in Kansas City to refuel and ended up pulling into Stapleton, it might have been 6 in the morning. And Lonnie

Wright and Larry Jones were stranded in New York by a snowstorm.” That was the early ABA. On the Air Force football beat, Moss was

struck by the poise and maturity of the players and had an especially good relationship with coach Ben Martin.

“The Post was an afternoon newspaper,

so that meant we came in about 6:30 in the morning,” Moss said. “Ben set it up this way. I’d call him at

home at about 6:45 in the morning and he’s ready to go.” In 1972, with clearance from the Post, Moss accepted an invitation

from the United States Olympic Committee to work as a public information officer at the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich. It

was the first of his 10 Olympics working in that capacity. On Sept. 5, Moss noticed a furor as he walked to the dining room in

the Olympic Village complex and soon got word of a hostage crisis in the Israeli team area. He stayed most of the day with

ABC commentators Bill Toomey and Willy Schoeffler, both of whom had Colorado ties. “The complex was built in such a

way that on occasion there were openings that you could look down into the (underground) garage,” Moss said. “We

were kind of standing and sitting next to one of these openings and they were getting some information on their walkie talkies.

They said the report was they were going to be leaving in a bus. We saw the bus pull out and it was headed for Furstenfeldbruck,

a small airfield. Gosh, it wasn’t very far away. Then they made the announcement within a short time that there had

been a shootout at the airport.” Eleven Israeli team members died in the Munich massacre — two at the Olympic complex

and nine at the airfield — and a German police officer and five of the Black September terrorists also died.

A few days later, the ending of the

gold-medal basketball game was replayed twice, and the Soviet Union’s last-second basket gave it a 51-50 victory over

the Americans. Working for the USOC, Moss was in the stands, astounded by the finish. Years later, he talked with Olympian Bobby Jones, who became a Denver

Nuggets forward. “Bobby Jones wasn’t in the game,” Moss said. “I don’t know if the rules prevented

(coach Hank Iba) from substituting or what, but I asked Bobby, ‘You think you could have stopped that play if you had

been in the game?’ He looked at me and said, ‘I know I would have stopped it.'” Moss continued to enjoy covering Air Force

and Martin blew up at him once — after Colorado’s 28-27 victory over the Falcons at the Academy in 1974.

It was the final scheduled meeting in a rivalry that will resume in 2019. Tensions had been high during the Vietnam War years

when Air Force traveled to the Boulder campus, and that was the backdrop to the end of the series. In that final game, Martin

played very conservatively at the end, running the ball and settling for a 50-yard field goal attempt that went just wide

with five seconds left. “We walk into the coach’s office and Ben had worn these two big galoshes because the field

was muddy,” Moss said. “They’re sitting there on the floor. Nobody’s saying anything and pretty soon

I say, ‘Ben, can you just give us a little review of the last minute or so of that game as to what you did?’

“He looked at me and picked up

one of those galoshes and threw it across the room and he said, ‘You know, you people have just watched one of the greatest

games ever in college football and you ask me a question like that!'” He later made up with Moss, explaining his late-game strategy.

Moss stuck with the Falcons through

the coaching tenures of Bill Parcells (for one year), plus Ken Hatfield, Fisher DeBerry and the early years of Troy Calhoun.

He also was involved in coverage of the Nuggets through their buildup years under general manager Carl Scheer, whose audacious

moves and signings — especially of David Thompson and Marvin Webster — helped force the ABA-NBA merger in 1976,

and into the early 1980s. By the mid-’80s, Moss became a dogged tracker of Denver’s quest to land a major-league baseball

franchise, often attending major league meetings. Denver billionaire Marvin Davis’ prospective purchase of the A’s and their

move to Denver had fallen through in 1977. Moss can rattle off the list of teams and ownerships that in later years flirted

with Denver, whether seriously or as a means of gaining leverage in seeking stadiums or better deals. San Francisco. Seattle.

Oakland (again). Pittsburgh. And he chronicled much of the maneuvering, which became farcical at times. In 1985, Davis made another run at the

A’s.

“The Rocky Mountain News ran

the story that the Oakland A’s were coming to Denver,” Moss said. That story was based on what former A’s

owner Charlie Finley told the News, and Finley claimed to have a “very reliable source” telling him the deal was

signed. Moss recalled A’s president Roy Eisenhardt telling him, “If you run that story it’s going to be

the worst example of journalism since Dewey and Truman.” The A’s didn’t come that time, either.

In mid-1991, the issue of National

League expansion was coming to a head, with Denver one of several candidates. “The News was on the ownership group here in Denver,”

Moss said. “I figure that the ownership group here is going to be the first to know and they’re not going to tell

the News you can’t come into this meeting. So I figure, ‘Geez, I’ve got to get a source,’ and boy

I did, it was like sitting in the room. “The word was that Denver was in and they were still debating over Tampa and Miami.

I got the story saying essentially that, that a source close to the negotiations indicates Denver’s going to be a Major

League Baseball city and the (MLB) expansion committee is still deciding between Tampa and Miami.” In mid-June, Commissioner Fay Vincent announced

that the expansion committee had recommended Denver and Miami, and official conformation came a month later.

The Rockies began play in 1993.

Moss was one of The Post’s writers

on the Rockies beat for 12 years. “The first game at Mile High Stadium was just unbelievable, with 80,000 people and the

way Eric Young got it started (with a leadoff home run), it was just amazing,” Moss said. “A lot of the media

that used to go to those owners meetings had gone through expansion teams and they all said you’re going to have the

most fun covering any team for about the first two or three years of an expansion team. And they were right. As different

players came in, it changed.” In recent years, Moss has been a general assignment reporter, helping out on virtually

all beats, and has written the popular Colorado Classics feature about figures from the state’s sports past. He received

the Football Writers Association of America’s Lifetime Achievement Award earlier this year, and he also was chosen for

the Colorado High Schools Activities Association Hall of Fame. His two children, Karen Mitsch and Andrew Moss, both live in

the Denver area. He's a Colorado Classic himself.

Photo courtesy John Leyba

|