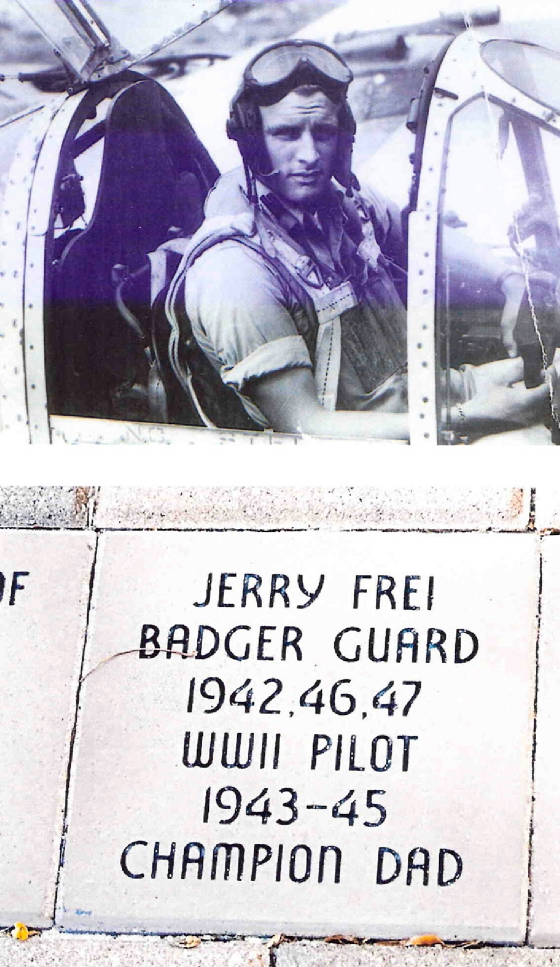

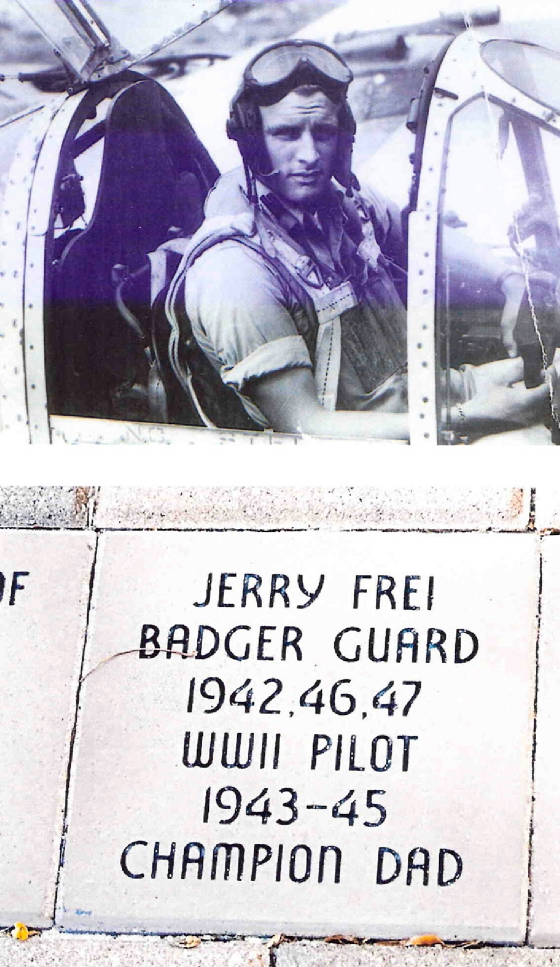

The brick is outside Camp Randall Stadium in Madison. The Veterans Day 2000 story that led to Third Down and a War to Go: Grateful for the Guard

One

man on the planet has earned both Super Bowl championship rings (twice) and the World War II Air Medal (three times). That

will not change. This is his story. In November 2000, I finally sat down and, with a tape recorder (remember those?)

rolling, asked my father, the former World War II pilot, former coach at the University of Oregon and a long-time NFL coach,

scout and administrator, to tell me about his wartime experiences. I waited disgracefully long to do it, of course. But I

did it in time. He died on February 16, 2001, three months after the original version of this story ran. He was one of the

youngest World War II veterans who had gone through full pilot training and flew a full tour of combat misssions. He would

have turned 100 on June 3, 2024. We've lost them. He is among the millions who have died since 2000. This is based on my November

12, 2000 Sunday Focus column in The Denver Post. I still am thankful to sports editor Kevin Dale and ace Sunday editor

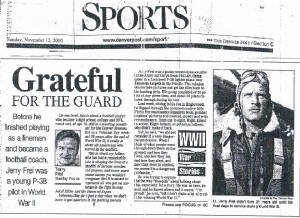

Obbie Harvey for allowing me to do the original story. * * * On one level, this is about a football player who became a high school, college and NFL coach

and, at age 76 in late 2000, still is a scouting consultant for the Denver Broncos. But on a Veterans Day weekend 55 years

after the end of World War II, it really is about all Americans who served in the conflict. This is about my father, who has had a remarkable

role in shaping the lives of a handful of famous coaches and players, and many more whose names you wouldn't recognize. But

it is meant to represent all those who put on the uniforms in the fight against Germany and Japan. Jerry Frei was a photo reconnaissance pilot in the

Army Air Corps / Air Forces from 1943-45, flying alone in a one-man, twin-engine Lockheed P-38 "Lightning"

fighter plane over enemy targets in the Pacific in advance of the bombing runs. The guns on the P-38 had been replaced with

cameras. The mandate was to take pictures and get the film back to the landing strip. Sometimes, he might be flying the only

plane on the mission. Other

times, there might be two in case cameras failed. He later would

say it was wrong to say he was unarmed. He had a pistol. It was understood what it might be used for. That wasn't for self-defense. His group consisted

of 20 pilots at any given time, and about 35 pilots rotated through during his tour. Last week, sitting in his den in Englewood, he flipped

through the commemorative 5th Air Force's 26th Photo Reconnaissance Squadron book, pointed to pilots' pictures and counted,

slowly and with remembrance, from one to eight. Eight killed in action. Eight fathers, or potential fathers, who didn't make

it back. Yet, he said, "we did not consider it a very dangerous profession. When I think of what people went through

down there on the ground, and how they lived, and how they ate, and how they slept, and how they were in combat, we weren't

in a dangerous profession." Later, I discovered he was talking about his many Wisconsin teammates in ground fighting, both

in the Pacific Theater and in Europe. A handful of Badgers were pilots. He was trying to explain that he was "sheepish"

about talking about this, especially for a story. He was no hero, he said, and he knows others had it worse. "I'm proud,"

he said, "but I don't claim a lot of credit for winning World War II." That's the point. It was a group effort. His story

is unique, yet startlingly typical at the same time. And so is something else, shamefully: Until last week, his baby boomer

son never had really sat down and talked with him at length about his World War II experience. Or even said "thanks." I had been to reunions

of the football teams he coached, from the 1949 Oregon state champions, the Grant High School Generals, to the Vietnam War-era

University of Oregon Ducks, hearing his players and assistant coaches such as Dan Fouts, George Seifert, John Robinson, Bruce

Snyder, Ahmad Rashad, Norv Turner and Gunther Cunningham -- and many more -- tell me how important he was to them. But this is different.

This is something he never really talked about much over the years, with his players or with his children. In this instance,

he represents millions in his generation.He was 16 when he graduated from high school in Stoughton,

Wisconsin., about 15 miles from Madison. He went to the nearby University of Wisconsin to play football for coach Harry Stuhldreher,

the quarterback in Notre Dame's Four Horsemen. He was a 185-pound lineman. When he was a 17-year-old freshman, he worked all

night at Toby and Moon's restaurant on the always-buzzing State Street near campus, then was awakened by his roommate and

fellow guard, Ken Currier, and told: "They bombed Pearl Harbor!" His response was typical on that Sunday morning.

"Where's Pearl Harbor?"

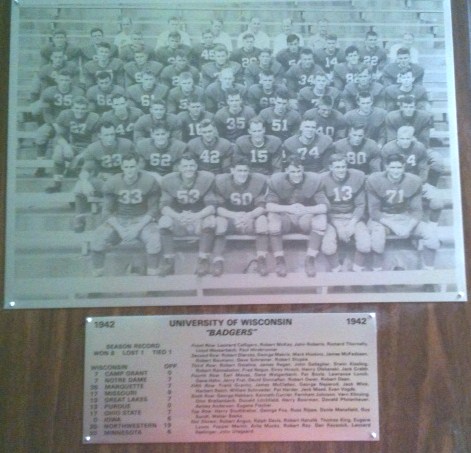

Jerry Frei (65) is next to fellow sophomore Elroy "Crazylegs"

Hirsch (40) in the 1942 varsity team picture. As the United States entered the war against the Axis powers, as the bad news

poured in through 1942, Jerry Frei was a sophomore guard and the youngest player on the Wisconsin varsity squad that went

8-1-1 behind halfback Elroy (soon-to-be-"Crazylegs") Hirsch, All-American end and Big Ten MVP Dave Schreiner (80),

fullback Pat "Hit 'em Again" Harder (34), tackle Bob Baumann (74) and co-captain Mark Hoskins (11). They lost only

to Iowa and tied Notre Dame. This all unfolded in a final-fling campus atmosphere -- not just for athletes, but for all young

men and many young women. After the Pearl Harbor attacks, most of the Badgers signed up for for one of the armed forces and

the Enlistted Reserve Corps with the understanding that they likely would be called up soon. The Badgers

beat Ohio State 17-7 on Halloween in Madison , but the final Associated Press poll had the Buckeyes No. 1 and Wisconsin No.

3. (Drunken sportswriters ...) The Helms Foundation got it right, naming the Badgers its national champion. Stuhldreher arranged for Frei to sign up for an Army

Air Corps reserve unit, because it was based in Madison. The Wisconsin coach told his guard that because he was so young,

only 18, he probably wouldn't be called into the service until at least after his junior season. Instead, the induction notice

came in February 1943. Frei had been in college three semesters. "At that point, we all wanted to go," he said. "All your

friends were going, and you were not going to stay in school." He was in the Army Air Corps/Army Air Forces, on his way

to becoming a pilot, almost by accident. "I had no inclination, no great desire to be a pilot," he said. "The first time

I ever was in an airplane was my first lesson in training." The Badgers scattered. Jerry Frei and Currier were among the Badgers who

entered the Army Air Corps, the predecessor of the Air Force. (By the end of the war, they were the United States Army Air

Forces.) "It was laughingly referred to as the Brown Shoe Air Corps," he said, "because we wore brown

shoes with Army uniforms. The uniforms didn't turn blue until it became the Air Force." As the war raged in Europe and the Pacific, he went

through Army basic training in Wichita Falls, Texas; then Air Corps indoctrination and training in several types of planes

in Arizona, California, Kansas and, of all places, La Junta, Colorado. Ultimately, he ended up in Coffeyville, Kansas, graduating

with "44E" -- the fifth group in 1944 to be trained in P-38 reconnaissance flights. Frei and his buddies were assigned to a photo recon

group in Europe, loaded onto a troop train and sent to Savannah, Georgia, their stopping-off point for Europe. But when they

got to Savannah, they were told they instead would be going to the Pacific -- and were sent right back on the train, back

across the country to San Francisco. By then, a four-man group of buddies from "44E" was tight, and assigned together because

of the accident of the alphabet -- Frei; Ed Crawford, from Texas; Madison Gillaspey, from Iowa; and Don Garbarino, from Oregon.

That would turn out to be pivotal later. They ended up with the 5th Air Force's 26th Photo Recon Squadron

at Biak Island, off the coast of New Guinea, in advance of the invasion of the Philippines. They were told their tour would be for one year and

300 combat flying hours. When they arrived, they also were very popular among their peers, because they were the rare P-38

pilots who had flown B-25 Mitchell medium bombers in training. Those planes, the "Fat Cats," were the only ones

that could be used to fly to Australia for supplies -- including meat, milk and beer -- and the four new arrivals often did

that duty, which didn't count as combat time. On September 18, 1944, three months after his 20th birthday, Frei flew the first of his 67 combat

recon missions. Let me say this again, for emphasis. He and perhaps one other pilot flew their planes, unarmed, over Japanese

targets in advance of the booming runs. In a shoulder holster, he carried that .45-caliber revolver. "They would pretty much leave you alone,"

he said of the forces of Japan. "You could get anti-aircraft fire, but as you looked out the back window, you could see

it behind you. Most of the times, we were coming in high and staying for such a short period of time. You went down one direction,

back over the target in the other direction and got out of there. "As soon as you got back into radio range, you would tell 'em, 'Yeah,

I got pictures, I'm on the way home, I'll be there about such-and-such time.' You'd get back and you'd buzz the home area,

saying, 'Here I am, come and get me at the airstrip and get my pictures out of the cameras.' "The newer you were and the younger you were,

the harder you buzzed, because you didn't think you were going to live, anyway. But as soon as you got halfway through, you

said, 'My God, I'm going to make it, maybe I'm going to last.' That's when you started flying more conservative, straight

and level. One of the guys who came over with us and went to another squad got killed buzzing. He hit a palm tree with his

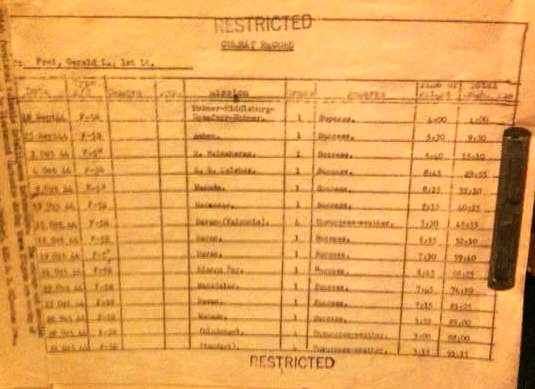

tail, and that calmed down a lot of people." The old hanging folder is Frei's flight record, and it sits in the top drawer of his desk at home, next to the video

machine he still uses to look over college football prospects. You can picture a sweating clerk typing information onto the

sheet after every mission 55 years ago, lining it up on the correct line, making sure the carbon paper is in place. The sheets

list 67 missions and targets with names such as Davao, N. Halmeras, Mindanao, Lianga Bay, Babuyan Island, Cape Bojeador, Solvec

Cove, Cagayan Valley, even Wenchou, China. Twice, Frei was sent to Australia for rest leave. The second time, the

squad moved from Biak Island to Lingayen, on the Lingayen Gulf to the north of Manila. When he finally caught up with his

squadron, he got off the transport plane at Lingayen and noticed one of the 26th's planes taking off.  "I asked one of our people, 'Who's that?' " Frei said. "He said

it was Madison Gillaspey (left), and he was going on a low-level mission to Ipo Dam. I went over to the squadron area, to

the others' tent. It always was Ed Crawford, Don Garbarino, Madison Gillaspey and me. But while I was gone, they'd moved another

pilot in with them when they got to Lingayen, so I was going to go get a cot and be the fifth." He didn't have to get the cot. "Madison Gillaspey never came back," Frei

said. "No one ever knew what happened, but we lost two planes over Ipo Dam." Hearing from Madison Gillaspey's fiancee: A WWII story of love and loss The Iowan was one

of the eight pilots killed. They were the victims of anti-aircraft fire or mechanical failure or ... who knows? Sometimes,

like Gillaspey, they just didn't make it back. After the war, located dogtags and wreckage provided some answers. Other pilots'

deaths never were explained.

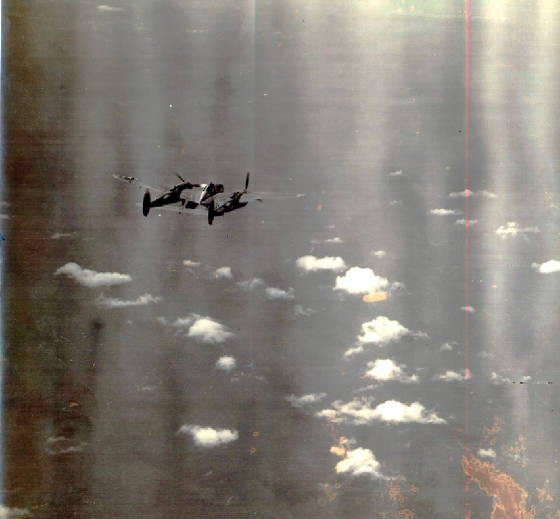

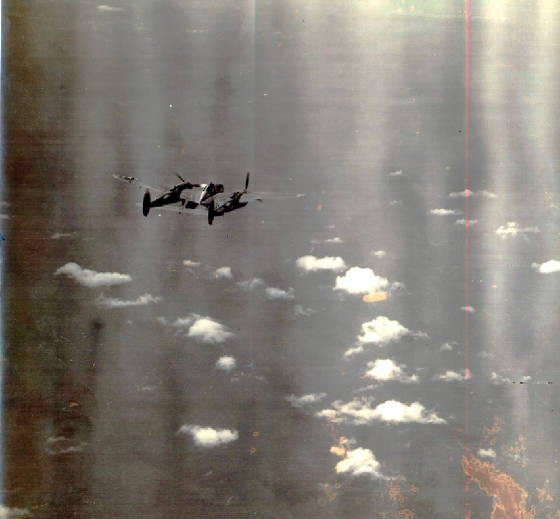

The P-38s each were painted with a pilot's

name, but the planes were in a pool and used by others. This is "Jerry Frei's plane" after another pilot's mission

left the plane heavily damaged. The toughest days

were March 22, 1945, when Frei flew two separate missions, to Northwest Manila and to the Cagayan Valley (the squadron received

a group citation); and April 15, when he flew an eight-hour mission from Lingayen, to a guerrilla airstrip for refueling,

then to Wenchou, the harbor port across the East China Sea from Japan. It was important work, much of it in support of the

6th Army, and short-term tension. "But again," he said, "I emphasize the point that mine was a nice war, if there

was such a thing. I didn't hurt anybody. I didn't kill anybody or shoot anybody. I didn't get shot at a lot, although we did

go through (Japanese) bombing raids when we were on the ground. But I also know what other men were going through, and it

was a lot worse." The 26th was ticketed to move to Okinawa in July 1945, and the squadron had stopped flying to prepare for the move.

Frei had flown 66 missions and 296 combat hours. But the operations officer said there was one mission available, to the Batan

Islands, north of Luzon. (The islands aren't to be confused with the Bataan Peninsula.)

On

June 28, Frei flew the two-plane mission, and his mission partner in the other plane used his cameras to take a picture of

him flying back to Lingayen. It is an innocent-looking picture today, a single plane above the ocean. Yet the pilot wasn't just heading back to

the airstrip. Figuratively speaking, he

was heading home. About that time, he heard the horrible news that two of his older Badgers teammates -- Marines Dave Schreiner

and Bob Baumann -- had been killed in the final days of the Battle of Okinawa. Soon, he was on a troop transport, heading

back to San Francisco. Two days from the West Coast, the ship's speakers blared the news about an atom bomb and Hiroshima.

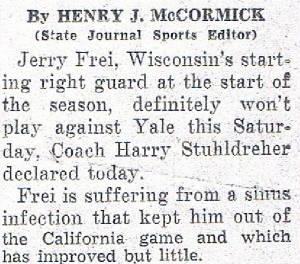

He married longtime Stoughton girlfriend Marian Benson on December 25, 1945, re-enrolled at Wisconsin and was a regular on Stuhldreher's 1946

and '47 Badgers teams. However, during his senior year, he was sidelined with with what Madison writers dutifully

reported to be severe sinus infections. The truth was, he had suffered chronic headaches and several concussions. Tio

a lessser degree, they had been an issue back in his freshman and sophomore years, too, as alluded to in the clippings below

about him giving up the game. He didn't bother that to tell military doctors giving him physicals. If he had, he moslt likely

would not have been accepted for flight training -- or accepted at all.

After his graduation, pondered his options. He had stayed in touch with pilot buddy Don Garbarino, who always had raved about Oregon. "I

had grown up where it was cold, really cold, and until I got in the service, I didn't realize the whole world wasn't like

that," Frei said. So after he was graduated from Wisconsin -- thanks to football, the GI Bill and his wife's right-out-of-college

teaching salary -- the couple loaded up the car and drove to Portland. "Don Garbarino hadn't told me it rained

a lot," he said. Within a week, he had a job as an assistant coach and teacher at Portland's Grant High, notable now as the school

where "Mr. Holland's Opus" was filmed. His head coach was Ted Ogdahl, who had earned the Silver Star in the Pacific

fighting. Frei soon was the head coach at Portland's Lincoln High, was an assistant at Willamette University in Salem -- again,

under Ogdahl -- and then joined the the University of Oregon staff in 1955. He was there 17 seasons, first as an assistant

to the legendary Len Casanova from 1955-66, then as head coach from 1967-71.

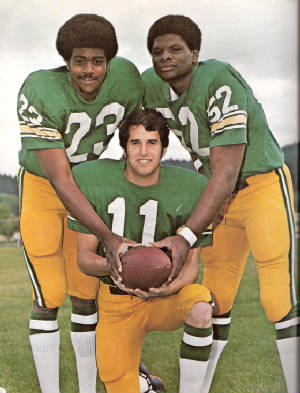

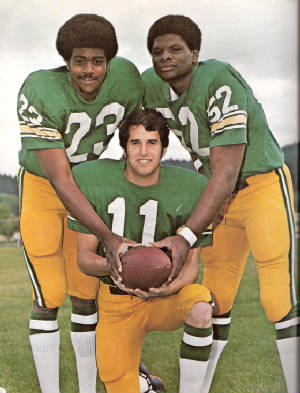

Ahmad Rashad, Dan Fouts, Tom Graham During the Vietnam era, many Oregonians claimed his program didn't have "discipline" because he allowed

players such as Bobby Moore (now Ahmad Rashad) and Tom Graham to wear their hair as they pleased; or didn't tell his players

to stay out of campus politics and the antiwar movement. He refused to call his players "kids." They were "young

men." One of the reasons, among the many, was that at age 20, he had been flying over Japanese targets, and he wasn't

going to treat 20-year-olds as children. I know they appreciated it, because they've told me that over the years, including

at a tribute weekend in Eugene organized by Fouts.

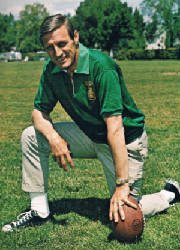

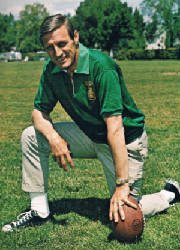

Left: Jerry Frei, 1971. At right, the

1970 Oregon staff: Ron Stratten, John Robinson (later USC and Rams head coach), Jack

Roche, Norm Chapman, Jerry Frei, Bruce Snyder (California and Arizona State head coach), John Marshall (long-time NFL defensive coordinator),

George Seifert (49ers and Panthers head coach), Dick Enright.

Not pictured: Graduate assistant Gunther Cunningham (Chiefs head coach). The

Oregon campus, as many were around the nation, was a cauldron of dissent. Dr. Charles Johnson, the school's president, was

a conciliator caught between rebelling students and irate Oregonians. While being treated for depression, he drove his Volkswagen

head-on into a lumber truck, and most considered it suicide. Amid the tumult, the Ducks finished second in the Pacific 8 in

1970, beating both USC and UCLA and ninth-rated Air Force. Jerry Frei was UPI's national coach of the week twice that season. As

it turned out his last game at Oregon was the 1971 Civil War. The Beavers won 30-29 and Dan Fouts years later told a story

about that game at Jerry Frei's memorial gathering in Denver, at which Tom Graham officiated. With Oregon hoping to drive

for a game-winning field goal, but still out of range, Fouts turned the wrong way to make a fourth-and-short handoff and came

off the field in tears. He said (incorrectly) that he had lost the game. He told those at the memorial that my dad immediately

and decisively, with everything going on, gave him a pep talk told him to keep his head up. After the game, Tom

Graham grabbed the microphone during the introduction and honoring of the seniors and declared: “I’m going to

be a Duck until the day I die.” (He was.) I was sitting in the

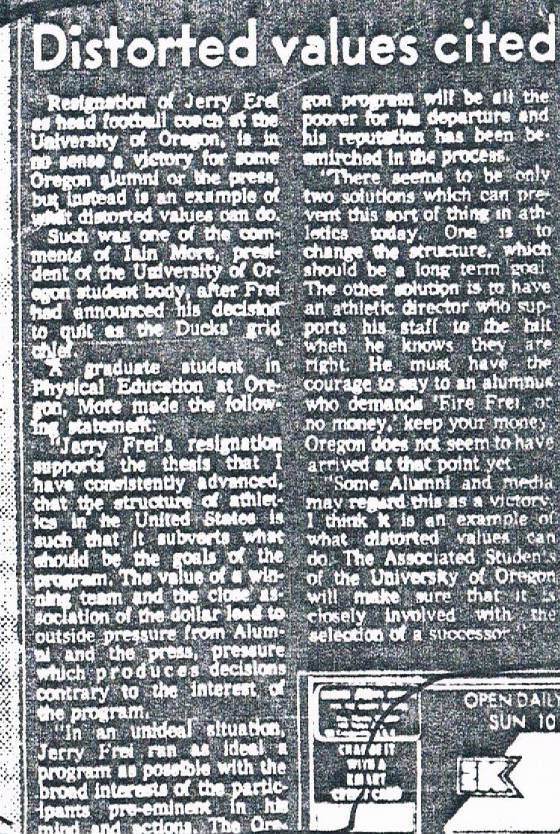

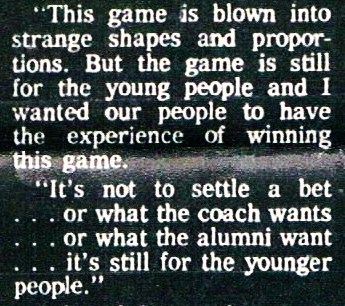

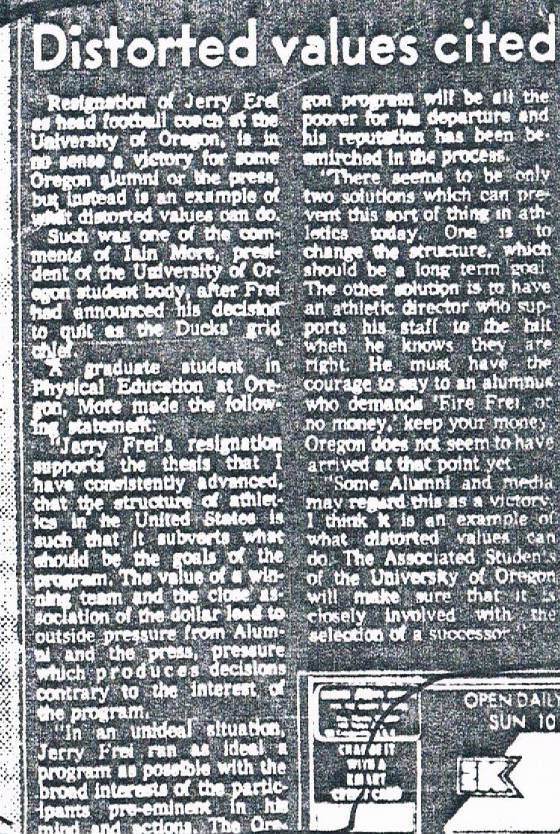

tiny coach's locker room when my dad met the press and said, among other things:  When Frei quit two months after that 1971 season, after much behind-the-scenes political maneuvering

that unfortunately still is common in college football, the radical student body president issued an eloquent statement of

support. The Eugene Register-Guard publisher came to our house, and the paper ran letters to the editor saying his battle with some boosters -- and not just over winning and losing -- shouldn't

have been allowed to cause his departure. (Note: Eventually, my 2009 roman a clef novel, The Witch's Season, was the thinly veiled story of that campus,

that team, and those times.)

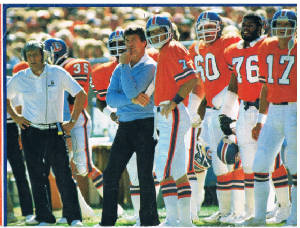

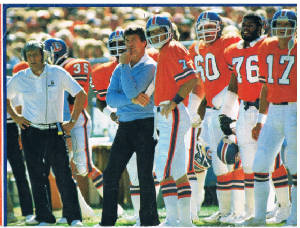

Jerry Frei in his two stints with the Broncos as offensive line coach. At left, his first stop, under under John Ralston.

He's at the left In the second photo, coaching under Dan Reeves.  `Jerry Frei left the Broncos to go to

Tampa Bay and work with one of his best friends, John McKay. He ended up back with Denver. Stanford coach John Ralston was moving to the Broncos, and he hired Frei as his offensive line coach. He moved on to

Tampa Bay and Chicago -- where he quickly considered Walter Payton his favorite NFL player ever -- before returning

to the Broncos when Dan Reeves became head coach. With Denver, he has been a coach, a scout, the director of college scouting

and now [in 2000] -- a consultant who still loves to watch practice and scouting tape, especially of the offensive linemen. Around him, he heard

the talk about the overdue gratitude and acknowledgment of what his generation did for us. And there's no other way to put

it: We're not all that sure we could have done it, or that today's youth would be as courageous. Maybe it was about naivete.

Maybe knowing the horrors of war, in a time of more destructive weaponry, is a good thing. But maybe we're just not as brave,

either. "I think all of us didn't feel like were being different," he said. "Or that we were doing anything

spectacular. Everybody did it. It wasn't, 'Look at me, I'm a soldier.' I don't think anyone was concerned about memorials

or anything like that. I think everyone was looking at it like, 'I did what I had to do.' Everyone who survived gave a big

sigh of relief, and felt sad for those who didn't." The least we can do is say "thanks." To them all. Postscripts:

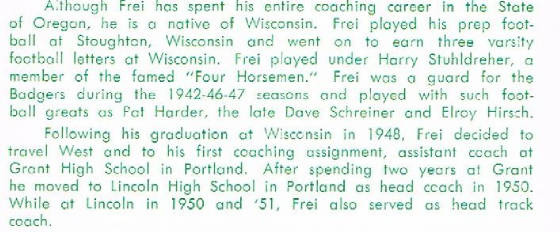

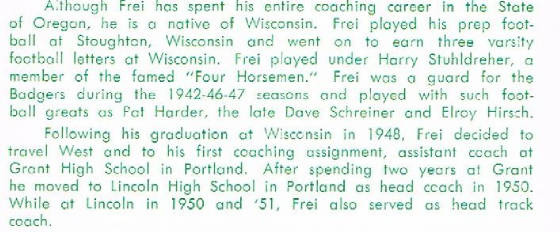

Notice anything missing from this coaching bio in the Oregon press guide? Yes, his World War II

service wasn't even mentioned. Also, the reference to the "late" Dave Schreiner doesn't explain that the two-time

All-American end, winner of the Chicago Tribune's Silver Football as the Big Ten MVP in 1942, and No. 11 overall

choice in the NFL draft, was killed in action. I heard from a lot of readers about this story, including from Madison Gillaspey's fiancee, who filled in some gaps

about his death, and others who belittled my naivete about how dangerous unarmed reconnaissance flights, often flying solo

over Japanese targets, were and about how coveted P-38 duty -- in any form -- was. "Oh, we all wanted to fly that plane,"

former Arkansas congressman John Paul Hammerschmidt, a decorated World War II pilot himself, later told me. When my father died,

his former players told me they were astounded to read of his World War II service. He never mentioned it to them and, as

noted, it wasn't mentioned in his Oregon media guide biography. My mother later pointed out another omission:

He hadn't told me that he had been awarded the World War II Air Medal three times -- the medal plus two Oak leaf clusters.  Also, I realized that everyone on that 1942 Wisconsin team, in the picture plaque on his den wall, had a story. That

picture was from the first day of 1942 fall practice and members of the "B" team were included. As it turned out

that was fortunate for me, since many of them still were alive and were great inteviews about the entire team and season.

I discovered that distinguished war-time military service was common up and down the roster, among stars and scrubs. I realized

I could have done a book like that on any team -- any team -- in the country and discovered much the same thing. That led

to Third Down and a War to Go, and it's why I have the picture wallet Schreiner

was carrying when he suffered his fatal wounds on my desk as I type. Once more, with feeling: Thanks to them

all.

Jack Elway and Jerry Frei, who

shared an office at the Broncos' Dove Valley headquarters, in the winning locker room after the Broncos beat Atlanta in

Super Bowl XXIII in Miami. They died three months apart in early 2001.

Jerry and Marian Frei |