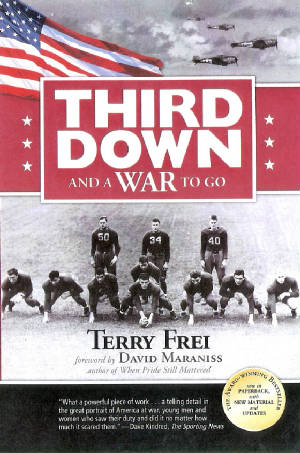

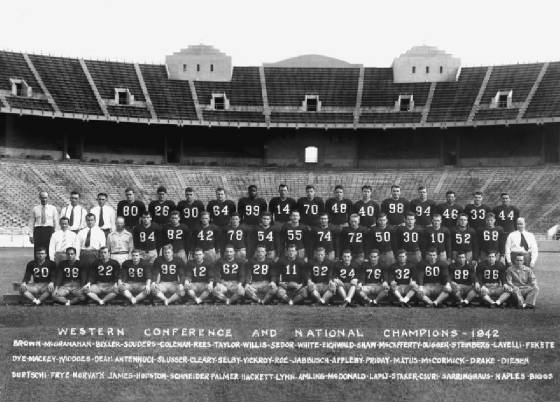

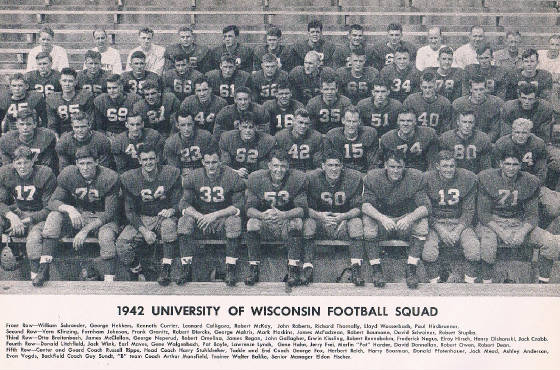

ELEVEN Massillon

The Badgers’ 1942 schedule was posted on the Camp Randall locker room

wall. When the boys arrived back from Purdue, the handwritten addendum

in the margin next to the upcoming Ohio State game jumped out at all of

them.

It

was one word.

MUST.

If the Badgers were going to be bona fide threats to win the league championship

for the first time since 1912, they MUST beat the vaunted Buckeyes.

Harry Stuhldreher

never spelled it out, but the Badgers understood that

he

didn’t like Paul Brown, and they inferred it involved resentment over how

Brown had usurped Stuhldreher’s title as the favorite football son of Massillon,

Ohio.

When Brown was a

kid in Massillon, he had heard of Knute Rockne,

but his hero

was a contemporary—local high school star Harry Stuhldreher.

What Rockne was to Stuhldreher, Stuhldreher was to Brown. Brown was

playing at Massillon High when Stuhldreher was one of the Four Horsemen

at Notre Dame. While Stuhldreher was at Villanova and then Wisconsin,

Brown coached Massillon for eight seasons, winning six consecutive

state championships. He stepped directly into the Ohio State head-coaching

position—which, in addition to the Notre Dame position, would have been

Stuhldreher’s dream job—in 1941. In Brown’s inaugural season, Ohio State

whipped Wisconsin 46–34.

Publicly,

Brown and Stuhldreher were respectful of each other. Actually,

the

Badgers knew Stuhldreher couldn’t stand Brown—and, without knowing,

they assumed the feeling was mutual. Discovering that your hometown

hero, the Four Horseman quarterback, believes you stumbled into a great job

and gives you the cold shoulder, well, that could be disillusioning.

Fred Negus, the sophomore center, was the only Badger starter from Ohio,

and he told his teammates how much he wanted to beat the team from his

home

state. His parents were coming to Madison to watch him play collegiately for the first time. He still was trying to convince his mother, raised

as a Quaker, that football wasn’t evil incarnate. “My mother

brought up that

she didn’t want me to hurt anyone,”

he recalled.

Stuhldreher was late for the Monday practice

after making a noon speech

to a Chicago organization, the

Wailing Wall. The players didn’t have the

nerve to

greet their tardy coach with a “Take Five!” order to run laps.

At the practice, Stuhldreher named Dave Schreiner

the game captain for

the second time in the season. That

night, Schreiner received a telegram at

the fraternity house

from the girls at Ann Emery Hall [where he worked in

the

cafeteria]:

CONGRATULATIONS WITH YOU AS OUR CAPTAIN

WE’RE SURE

OF OUR GOAL.

Schreiner also gently lectured his parents

again in a letter that he couldn’t

be expected to line

up tickets for everyone in Lancaster who wanted to go to

the

game.

★ ★ ★

Washington, Oct. 28 (AP)—American and Japanese warships boiled

through the southwest Pacific in a titanic slugging match for control

of

the bomb-scarred Guadalcanal airfield Wednesday while

on the island

itself land forces were locked in mortal combat.

In the epic land battle on the north shore of Guadalcanal,

Japanese

forces broke through the American south flank during

the night of Oct.

25–26 but were thrown back by army

troops who regained their temporarily

lost positions. On

the west flank, held by Marines against a smashing

series

of attacks that have been underway since last Friday, the Navy

reported

the enemy was forced to give ground in “heavy fighting.”

★ ★ ★

In the new Associated Press weekly poll, the Badgers were sixth behind

Ohio State, Georgia, Alabama, Notre Dame, and Georgia Tech. In Columbus,

Paul Brown told writers the rankings were “generally classified

as a silly

type of thing by the men who play the game and

know the score.”

Indeed, the concept was absurd. Even if

some of them were sober, how

could writers from all corners

of the country evaluate various teams, some—

or

most—of which they never had seen play? Caveat emptor.

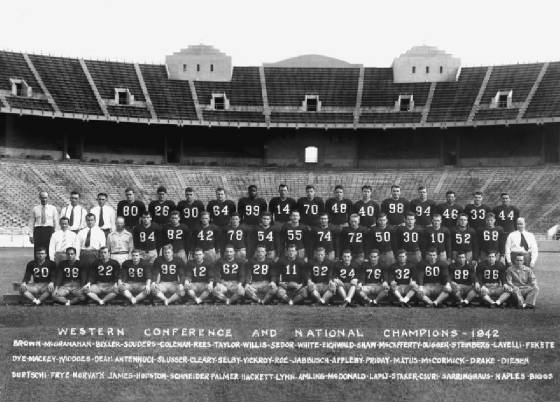

The top-rated Buckeyes had a host of stars, including end Dante Lavelli,

quarterback George Lynn, halfbacks Paul Sarringhaus and Les Horvath, and

fullback Gene Fekete.

To preview the game,

Stuhldreher consented to an interview with Lew

Bryer of the Columbus

Citizen. He tried to upstage Paul Brown in Columbus,

and Bryer’s story was reprinted in the Wisconsin State Journal.

“I

keep picturing the boys who are playing for me as they may be a year

from now, battling a Jap or a Nazi with a bayonet,” Stuhldreher said. “We’ve

always wanted our players tough. Now we want them tougher than ever.

There’s a real parallel between football and modern warfare. And don’t think

the boys themselves don’t realize it. There’s a different

attitude this fall over

anything I’ve seen either as

a player or coach. The boys are preparing themselves

not

only for the games to come, but for their future in the armed services.

Their imaginations are fired by what the Rangers and Commandos are

doing to outsmart and outgut the enemy. Eventually the present day football

players will go a long way in helping to win this war.”

Stuhldreher continued:

We coaches don't like to be asked: 'How many boys will you lose

to the armed forces?' We don’t lose them. We contribute

them.

Teamwork is an absolute essential in football.

It’s just as essential

in warfare. The

fighter planes which clear the air for the bombers,

the

preparatory barrages from the artillery before an attack,

the big tanks which open paths through the barbed wire entanglements—

they’re the blockers out in front of the ballcarrier. The

ballcarrier couldn’t function without his blockers in war any more

than he could in football.

The

sort of war we’re fighting nowadays puts a burden on stamina.

You can’t get stamina out of a book. The sort of conditioning

work which Rock used to give us at Notre Dame, the sort which

Paul Brown gives Ohio State players and the sort I try to give my

boys is what it takes. It used to be well worthwhile just

from a

standpoint of preparing a youngster for

the field of battle of life.

It’s much

more worthwhile now in preparing a youngster for the

big

battle he may be in within the next year.

Some of my friends feel that it seems brutal

to be preparing

young men for war. It doesn’t

seem brutal to me. It seems the

opposite. We’re

in it. They’ll be in it soon. All of us may be in

it before it’s over. I like to think I’m improving my chances of

my boys coming through it through what they’re getting on the football field, the stamina, teamwork, coordination which goes to

make a good football player also goes to make a good soldier.

One of my big regrets is that we can’t have the whole student

body taking the training we give our football squad. It would

improve their chances, too.

The campus was in a celebratory mode, with the Homecoming festivities—

Friday pep rally, Saturday

game and dance—on Halloween weekend.

Stuhldreher’s

remarks were another reminder that this was part of the last

hurrah

for the men on campus, players and non-players alike.

★ ★ ★

The Buckeyes left

Columbus Thursday, switching trains in Chicago and

stopping

in Janesville, Wisconsin, for the night. On Friday, they checked

into

the Park Hotel downtown. Some players went to a movie, while others

remained at the hotel.

Meanwhile, at the

Friday night pep rally on the lower campus, attended

by about

eight thousand, Roundy Coughlin gave his usual fire-’em-up

speech,

and Stuhldreher and Dave Schreiner thanked the fans for their support

before the team, as was the game-eve custom, headed off to spend the

night at the Maple Bluff Country Club.

The

“fun” was just getting started.

The next morning’s Daily Cardinal (a rare student newspaper with a Saturday edition) reported that a disturbance

in downtown Madison was ongoing

at press time and had started

“within 10 minutes after the close of the pep

rally.”

The number involved and the extent of the rowdiness would

be debated

for days. The student paper put the number of

those in the mob at four thousand,

and the State

Journal ’s estimate was five thousand. The Daily Cardinal

said the event involved “students . . . marching down State Street, blocking

traffic, rocking cars and trampling everything in their path.”

The State Journal

labeled it a “three-hour

near-riot,” then erased the “near” over the next

few days.

The Daily Cardinal ’s account was more detailed than those in the “regular” newspapers. It reported the

mob went back and forth between campus

and the Capitol Square,

breaking windows on State Street businesses and

rocking—but

apparently not turning over—cars. The worst incident took

place

in front of the Orpheum Theater, where police officers were pelted

with water and eggs. The cops responded by spraying tear gas into the crowd.

Wind carried the tear gas right back at the policemen, and they scrambled

into the theater, giving the impression they were retreating in the face of

the mob. Other officers at the epicenter of the action, at State and Johnson

Streets, claimed they were targets of thrown glass and debris. They used tear

gas and fire hoses to defend themselves. Students later claimed that water

broke some of the windows.

Some of the Buckeyes

got caught up in the mess, even breathing in tear

gas before

making it back to their hotel. “We were right by the capitol building,

and instead of getting a good night’s rest, we were kept up all night by

people banging on our doors and things like that,” recalled Fekete, the Buckeyes’

star fullback. “The Wisconsin goblins!”

Some of the Buckeyes would have been awake, anyway, because they were

fighting dysentery and racing their roommates to the toilets.

Police made thirty-two arrests that night, and most of the miscreants had

headaches as they appeared before Superior Court Judge Roy Proctor the

next morning—about when the Buckeyes were eating breakfast at the Park

Hotel. Bails were set from two to fifteen dollars. Many of the arrests involved

students who had left taverns carrying beer glasses or bottles and then thrown

them.

The judge got everyone through his court

in time for him to go to the

football game.

★ ★ ★

UW freshman Tom

Butler, a journalism student and sports fan, was typical

of

the Madison students the next morning. He approached Camp Randall

Stadium from the north, walking across the baseball and practice fields,

marveling at the good weather, and feeling the excitement about the upcoming

game and enmity for the Buckeyes. The UW had a lot of rivals. Notre

Dame and Ohio State were at the top of Stuhldreher’s list. To the students,

the most hated rivals were Minnesota and Ohio State. “We hated Ohio State

with a passion,” Butler recalled. But the Buckeyes were on both

lists, and that

also increased the players’ intensity

that day.

The Ohio State party arrived at the stadium

about ninety minutes before

kickoff, and the Buckeyes walked

around the field before going to the locker

room. Gene Fekete,

giving Pat Harder a run for his money as the league’s

best

fullback, noticed the huge spools of telephone wires on the sideline,

near

the goal line. According to the next day’s Capital Times, he pointedly

asked a worker if the spools were kept that close to

the sideline during the

game. “They’d better

not,” Fekete said. “I’ll be down here quite a bit.” Fekete

disputed

that report, and it seems likely that the Capital Times reporter either believed, or didn’t care to check, an unreliable second-hand story

passed

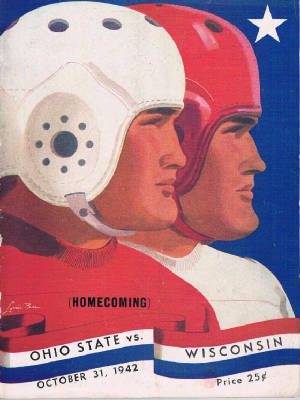

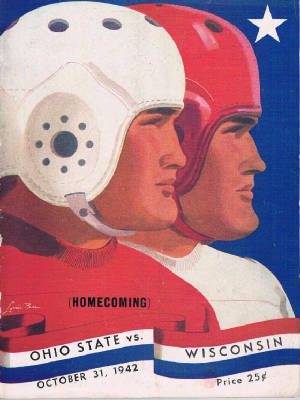

For two bits, fans could

treat themselves to the game program before the

Halloween showdown for the Big Ten lead.

along from someone on the field. Regardless,

the report and Fekete’s alleged remarks got widespread play after the fact.

The

Badgers had been on the field loosening up for nearly a half-hour

when some Buckeyes emerged from the locker room. None of them were

starters. Fekete and his fellow first-stringers finally took the field at 1:52

p.m., or only eight minutes before the scheduled kickoff. The Badgers considered

that insulting, but it wasn’t intended to be. Some of the Buckeyes still

were struggling with dysentery, and Ohio State’s coaching staff

put out the

word that it must have had something to do with

the Madison water. “Everybody

was tired and worn out,”

recalled Charles Csuri, the Buckeyes’ standout

tackle.

“There wasn’t any question that dysentery affected our squad.” Years

later, Csuri remained curious whether the outbreak was caused by something

the Buckeyes ate or drank before they left Columbus, during the trip, or after

they arrived in Madison.

Fekete wasn’t

sure, either, but he was adamant that many of the Buckeyes

were

having to make repeated trips to the toilet. “We had dinner on Friday

night in Madison, and maybe we’re not used to that real rich Wisconsin

Dairyland food,” he said years later, laughing. “Whether it was that or the

water on the train, that Saturday morning, I would say most of the team had

dysentery.”

Early-arriving fans got to see the 150-member marching band parade into

the stadium with the Navy men from the radio communications school and

the WAVES in formation behind them. Men from the Army Air Forces technical

school also sat together in one section.

College

crowds everywhere were beginning to look like those traditionally

at Army-Navy games.

★ ★ ★

London, Oct. 31 (AP)—Fifty German bombers smashed with bombs

and machine guns at southeastern England Saturday in the biggest Nazi

attack since the 1940 Battle of Britain, concentrating their assault on

shopper-crowded streets at Canterbury, where Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt

was a visitor only Friday. Roaring in at dusk, the raiders dropped

bombs in haphazard fashion and machine-gunned a working class area

and then a shopping street.

★ ★ ★

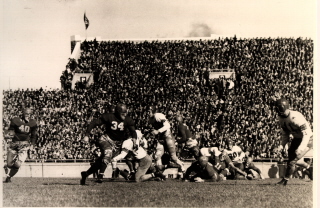

The game was still scoreless when the Badgers began their third possession

from the Wisconsin

20. On the first play, Elroy Hirsch took the snap

and

started to his right. Pat Harder escorted him, focusing on Ohio State

star George Lynn. Harder leveled Lynn, and Hirsch hurdled them both and

was in the open field. Looking at a picture of that play years later, Hirsch

laughed. “It’s amazing what fear can do,”

he said.

With the help of other blocks from Bob Hanzlik and Bob Baumann,

Hirsch made it to the Ohio State 21 for a 59-yard gain

before Buckeye

Tommy James pulled him down.

The State Journal ’s Willard R. Smith said on that play Hirsch ran “like a scared jackrabbit

on the desert with only sagebrush

and cactus

to hinder him.” (“Jackrabbit” Hirsch didn’t catch on.)

The

scribes noticed that Otto Hirsch, Elroy’s father, was sitting in front

of the press box, and they watched his reaction to the plays on the field,

especially Elroy’s runs. They noted that Otto missed the start of the

long run

because he was retrieving a feather

that had blown out of his hat. After the

run,

he hollered to his son, “You should have gone all the way!”

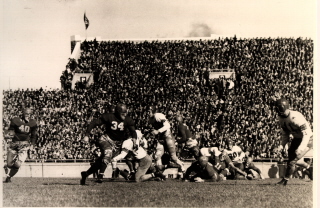

Elroy Hirsch (40) is about

to take advantage of a crushing block from Pat Harder

(34) and break into the open field for the long gain that set up the Badgers’ first

touchdown against Ohio State.

A few plays later,

Harder scored from the 1. Hirsch pulled Harder out of that pile and hugged the rugged fullback. If you needed a yard, you gave the

ball to Harder, and none of the Badgers begrudged that. Harder’s

extra point

gave the Badgers a 7–0 lead with 13:36

left in the first half.

With Schreiner sealing one side, the Buckeyes couldn’t move against the

Badgers. Wisconsin threatened to get the lead to two touchdowns, but the

Buckeyes managed to bat down a Hirsch pass intended for Schreiner on the

goal line, and the Badgers settled for a 37-yard Harder field goal to

make it

10–0. That’s the way it stood at the

half.

Thirty

more minutes, the Badgers told themselves—and each other—in the locker room.

On the field, the Homecoming festivities were altered for

the times. At

one point, part of the band started to spell

out OHIO, mimicking the Ohio

State band’s famous maneuver,

and the stunned Wisconsin fans booed. Long

before those band

members could get to the conclusion, the dotting of the

“I,”

the rest of the band formed a tank, “ran over” the Ohio formation, and

“flattened” it. The crowd laughed and cheered.

The halftime program was a tribute

to former Wisconsin students and

residents serving in the

military, and representatives of the Marines, Army,

and Navy

made speeches. After each one, the band played the appropriate

song—“The

Marine’s Hymn,” “Anchors Aweigh,” or “You’re in the Army

Now.”

The Marine representative was Lieutenant Colonel Chester

L. Fordney,

chief of the Central Recruiting District. “Wisconsin’s

men are fighting men,”

he told the crowd and the international

radio audience that included U.S.

troops around the world.

“They are demonstrating that on the football field

today.

But Wisconsin men also are serving from the Halls of Montezuma to

the shores of Tripoli.”

He probably knew that many of the Badgers had signed up for the Marine

Reserves.

As the halftime intermission ended, a group of Wisconsin

fans turned to

the broadcast booth in the press box and taunted

NBC’s Bill Stern, who on

the radio earlier in the week

had picked Ohio State to win.

But the game was far from over.

★ ★ ★

On their second possession of the second half, the Buckeyes marched 96

yards for the touchdown that got them within 3 points. Fekete scored the

touchdown on a 4-yard plunge, and the Badgers were served notice that the favorites weren’t going

to fold.

Hirsch and Schreiner put it away, though—through the air. Hirsch hit

Schreiner for 12 yards to get the Badgers within striking distance. Then,

from the Buckeye 14, Hirsch faked a run to the right and got off a floater for

Schreiner, who was wide open moving toward the goal line. Recalled the

other

end, Bob Hanzlik: “Dave bobbled the ball, he was all by himself and

almost dropped it, but—and

this was typical Schreiner—he overcame it.”

Schreiner drew in the ball and the Badgers were in control.

The Harder conversion kick made it 17–7. A Hirsch interception ended

the last Ohio State threat, and bedlam broke loose at the final gun.

The Badgers’ stars shone, beginning with Hirsch’s 118 yards on only 13

carries. His Ohio State counterpart, Paul Sarringhaus, had 55 yards on the

same number of attempts. And Harder won the battle of fullbacks, outgaining

Fekete 97–65. Schreiner again was the hero defensively, and the

Badger

coaches later determined from film study that the

Buckeyes had gained only

4 yards around his end. When the

Badgers were on defense, he was working

against Ohio State

sophomore tackle Bill Willis, who went on to be an

All-American

in 1943 and 1944. “The guy he was going against was an All-

American, and Dave put him on his butt,” recalled Erv Kissling, the reserve

halfback, who watched from the sideline.

With their first victory over Ohio

State since 1918, the Badgers were on

top of the world—and

on track to win their first conference title in thirty

years.

The Badgers had beaten the nation’s number-one-rated team, but there

was so little emphasis on such imaginary malarkey, most of the fans knew

neither of the poll nor the rankings. More important to Wisconsin fans, the

Badgers had taken control of the Big Ten Conference race. After that day’s

games, the Badgers were the only undefeated team in conference play, at

2–0. Ohio State was 3–1, and Illinois, Minnesota, Iowa, and Michigan were

2–1. As long as the Badgers kept winning, they wouldn’t have

to worry about

playing one less conference game than the

Buckeyes.

In the Wisconsin dressing room, Stuhldreher told the boys how proud he

was but that they needed to keep it going. Outside, the scribes couldn’t hear

anything but his final line: “Let’s go all the way!” The boys hollered,

and the

doors opened.

Otto Hirsch was one of the many fathers

in the raucous locker room.

Schreiner paraded with the game

ball, lifted out of the pile at the final gun.

An exhausted

Harder couldn’t keep his balance and needed help tying his

shoes.

The State

Journal talked with Schreiner for a sidebar story. “I don’t believe

we could have won if it hadn’t been for coordinated

teamwork,” Schreiner

was quoted as saying. “This

was distinctly a team victory, and that’s the way

games

should be won. And, boy, I was nervous on that perfect touchdown

pass

from Elroy Hirsch.”

The sign on the locker room chalkboard, scribbled by manager Eugene

Fischer, announced: “Seven down, three to go.”

Stuhldreher

went to the visiting dressing room, but the door still was

closed.

He briefly waited outside with reporters. Paul Brown emerged, spotted

Stuhldreher,

and shook his hand, with the Columbus Dispatch writers, among others, watching closely enough to reproduce the conversation in

print the next morning.

“Congratulations, Harry,” Brown said. “You

had the best ball team—today

at least.”

Responded Stuhldreher, “Thanks, Paul. Sorry it had to be this way.”

He almost sounded as if he meant it.

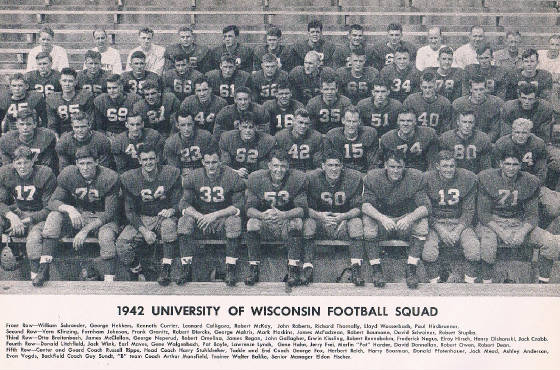

The Badgers’ stars

celebrate the team’s victory over Ohio State with their coach.

Mark Hoskins, Dave Schreiner, Pat Harder, and Elroy Hirsch get giddy with Harry

Stuhldreher, at center.

At first, as

he spoke with reporters, Brown was angry and terse. The Capital

Times said he greeted reporters with: “I’ll

give you a statement. Quote: Wisconsin won the ballgame.

Congratulations. Unquote.” But then he added,

“Wisconsin

has a good ballclub.”

Brown was more philosophical a few minutes later when he talked with

Columbus reporters in the dressing room. “You can’t take anything away

from Wisconsin,” he said, according to the Columbus Dispatch. “They

have a great football team and we have an ordinary one. Today

they were better

than we were. They were inspired and they

had the whole crowd cheering

for them.”

Brown said a loss removed some of the pressure. “I had no dreams. I kept

saying it would come sooner or later. It just wasn’t to be. From the time we

left home, even in practice things have been funny. Everything has conspired

to do us wrong. And this transportation problem and staying in the hotel

in

the town where the game is being played didn’t help

us either.”

The game would become known in Ohio State’s annals as “The Bad Water

Game.”

After the word filtered back to Madison that Brown later

said the Buckeyes

were weakened because of dysentery and

blamed the “bad” water in

Madison, the Badgers

scoffed. Years later, the Badgers still considered that

sour

grapes.

“Brown was complaining that there was so much noise they couldn’t sleep,

but that was a lot of B.S.,” recalled reserve tackle Jack Crabb. “We just beat

the shit out of them.”

Csuri, the Ohio State tackle, was

decisive when asked if Wisconsin saw the

real Buckeyes on

the Camp Randall field. “No,” Csuri said. “I’m convinced

of that.”

Looking back sixty years later, Fekete said the most graphic example of the

Buckeyes’ illness that day came on a play on which Les Horvath carried

the

ball. “I did a spinner play and handed off to Les,”

Fekete said. “Right in front

of our Ohio State bench,

about three Wisconsin guys just buried him. He

got up real

slow and walked over to Coach Brown. He said, ‘Coach, I think I

just did something in my pants!’ Paul Brown’s words were, ‘Les, you get back

in there! Better men than you have done something in their pants!’ ”

Bottom line: On the only afternoon when two of the nation’s best 1942

teams were on the field together, Wisconsin was better.

That day, Columbus Dispatch sportswriter Paul Hornung typed

away for his readers. The next morning his story began: “MADISON,

WIS.,

OCT. 31—The honeymoon is over; the ride on the

clouds is ended; we’re

just common folks again, we

Buckeyes.”

★ ★ ★

A teenaged Badgers fan, Nancy Schumacher, had graduated from high

school in Mineral Point the previous June. She put off going to college

for a

year to work in the Chain Belt plant in Milwaukee,

where she helped make

cases for anti-aircraft guns.

A star-struck Nancy kept a scrapbook of the Badgers’ season. After pasting

down a newspaper picture of Dave Schreiner sitting between two coeds, she

wrote “PHOOEY” beneath it.

Her father, Art, was a former UW letterman

and thus had tickets on the

50-yard line. Nancy sat in other

seats with her mother and planned to join

some of her student

friends on State Street after the game. But when heavy

rains

began, she decided to wait under the stands and was excited to notice

some of the players passing by.

She began asking them for autographs on her program. Bob Baumann,

the big tackle, smiled and teased Nancy that it would be only fair if

she gave

him her autograph, too. Embarrassed at first, she

signed. They talked until

the rains let up, and then they

went their separate ways, Baumann to meet

his fiancée,

Arlene Bahr, and Nancy to hook up with friends.

Nancy discovered that a group of about five hundred fans,

most of them

students, were celebrating under the watchful

eye of Madison police officers,

who had replenished their

tear gas supply and were wondering if the Halloween

atmosphere

might add to the trouble.

“We went uptown and partied at the Park Hotel,” recalled Tom Butler.

“Some guys were tipping over the sand-filled cigarette deals, and

everyone

was snake-dancing up State Street. It was just huge.”

However, the night’s festivities, including the Homecoming dance, went

peacefully.

(Many of the men on both teams mentioned here were

World War II heroes, and not all of them returned alive.

More on Third Down and a War to Go.)