February 26, 2025

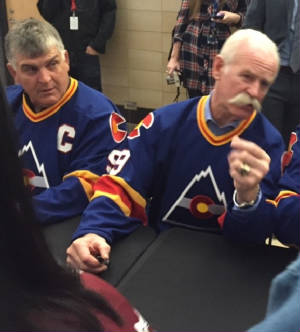

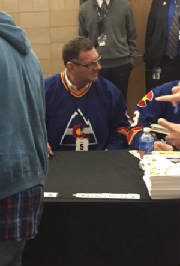

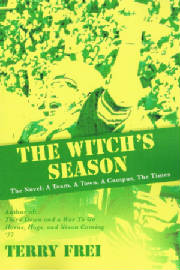

One-time Rockies captains Wilf Paiement

and

Lanny McDonald at 2015 Avalanche game

Each time the New Jersey Devils and Colorado Avlanche meet in Denver, as they will Wednesday, I flash back. That's

because to some of us who either saw it or cared enough to learn of the NHL's first foray in Colorado from 1976 to 1982, the

Devils once were the carnival act that was the original and unforgettable Colorado Rockies.

Rocky Hockey was a great training ground for me, and I enjoyed

it immensely.

My involvement began in 1977, when I had been at the Denver Post for less than a year after graduating from

CU. I was assigned to cover the Rockies, taking over the beat for the team’s second season in Denver.

What follows —

my recollections of Rocky Hockey, adapted from a section in my 2010 book Playing Piano in a Brothel — barely scratches the surface. Most important: I was there.

I saw all of this. I heard it. I wrote about it. The Rockies only made the playoffs once, the most games they won in a single

season was 22, and they went through three ownerships and virtually from start to finish seemed to be in danger of folding

or moving. The locker-room door was revolving, but some fine players and good guys passed through, and were often traded for

each other.

We

take you back to the thrilling days of yesteryear ...

Jack Vickers, who went on to gain greater recognition in the sporting world as the patriarch of

The International golf tournament, purchased the NHL’s Kansas City Scouts in 1976 and moved them to Denver. Only two

seasons old when it came to Colorado, the franchise had been under-capitalized and ineptly run as an expansion franchise in

Kansas City. The franchise would have had a better chance as a start-from-scratch expansion team. The Scouts dug a hole and

expectations would have been lower for a team implementing a patient building strategy.

In 1977-78, under first-year coach Pat Kelly, whose background as a minor-league player-coach

seemed familiar to those who had taken in the new movie, "Slap Shot," the Rockies put together an entertaining stretch

run and captured the attention of the market in my first season on the beat. The Rockies (19-40-21) sneaked into the playoffs

as the 12th and final qualifier in the 17-team league, lost to the Philadelphia Flyers in an entertaining two-game mini-series

in the first round, sold out the home game, and seemed to kindle hope for the future. But Vickers undercut the momentum during

the series by publicly bemoaning the team’s lease terms with the city. Soon, Vickers agreed to sell the Rockies to New

Jersey trucking company operator Arthur Imperatore.

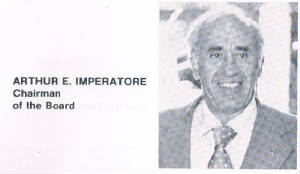

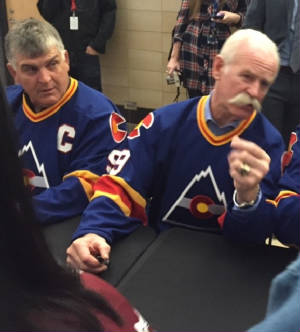

Arthur Imperatore in the Rockies'

media guide

At the news conference

announcing the sale at Mayor Bill McNichols’ office, Imperatore said he was hoping to operate the team in Denver until

the new arena was open in the New Jersey Meadowlands complex and then to gain approval to move it to East Rutherford. Standing

next to Vickers, Imperatore told us: “I’m buying the team with the expectation of bringing it into my home area,

which is New Jersey. I was born there, grew up there, and became a hockey nut there.”

I even stood on a chair to ask

whether they really expected Colorado fans to support a lame-duck franchise, and the fact that Imperatore was genuinely surprised

at the impudence of the question indicated to me that nobody involved in all of this had leveled with him. I admired how open

he was, but it was incredible that it had gotten to this point without someone at the NHL saying, “Uh, fellas, that

won’t work.”

Sure enough, the NHL quickly made it clear it wouldn’t commit the Meadowlands to Imperatore. It was planning

to award New Jersey as an expansion market.

Imperatore went through with the purchase of the team and put his stepson, Armand Pohan,

in charge. Pohan was brilliant, and one of the reasons I liked him was that he pretty much admitted that he and his stepfather

had been naive when they bought the team. They tried to make the best of it; they really did, in part because to do otherwise

would have been financial lunacy.

Pat Kelly was fired during that 1978–79 season. (He went on to be instrumental in the

re-founding of the East Coast Hockey League, which morphed into the ECHL, and its trophy is named after him. Avalanche coach

Jared Bednar raised it as both a South Carolina Stingrays player and coach, and the Colorado Eagles won it in 2017 and 2018.) Affable

team executive Aldo Guidolin finished that season as the Rockies' interim coach. The record was an abysmal 15–53–12,

erasing all the momentum of the previous season’s playoff berth. Arthur Imperatore, Armand Pohan, and general manager

Ray Miron decided they needed to do something dramatic.

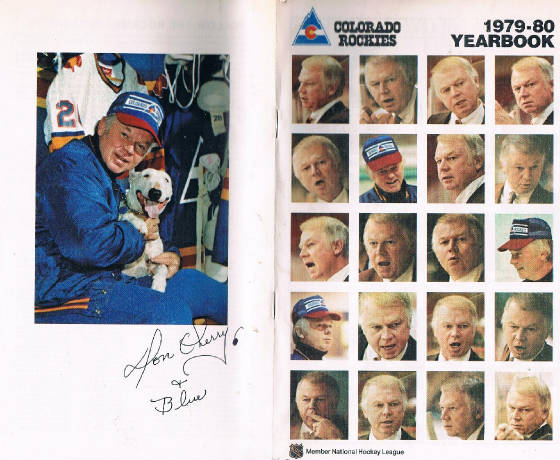

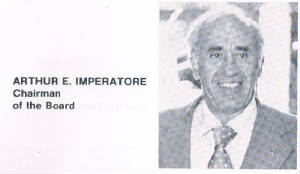

To fill the coaching vacancy, the Rockies hired Don Cherry

In later years, Cherry—“Grapes”—went from well-known as a coach to legendary as a broadcaster.

A fixture on Hockey Night in Canada’s “Coach’s Corner,” the bombastic Cherry shot from the

hip, in both loud voice and loud suits and sport coats. His “Rock ’Em Sock ’Em” videos became huge

sellers in Canada. He’s a watchdog for old-fashioned, old school Canadian hockey values and is variously revered or

ridiculed for his reluctance—no, his refusal to evolve with the game and the times. His fame is international and his

influence immense.

None of this might have happened if his stint with the Rockies had gone better. I enjoyed covering him, and I have

to say that he was a beat writer’s dream. Cherry had just left Boston, where he and general manager Harry Sinden had

a venomous relationship that led to Cherry’s exit after a semifinal round playoff loss to Montreal—one that included

a too-many-men-on-the-ice penalty on the Bruins in the final two minutes of regulation in the deciding Game 7. The Bruins

were ahead by a goal at the time, but the Canadiens tied it up on a power play and won the game in overtime.

Regardless, Cherry’s

record at Boston was impressive. The belief that the players universally loved him was misleading. Those who were among his

favorites indeed embraced him — in fact to a degree I never had seen before nor have seen since in covering major-league

sports. Those on his bad side bit their tongues and played on.

He got into coaching by accident. After a journeyman’s career

in the minor leagues—he got into one playoff game with the Bruins in 1955—he tried his hand at construction.

“My specialty

was the jackhammer,” he told me. “I liked it. It was a good honest job. But I got laid off in the recession there,

and I couldn’t find any other job. I tried selling cars, but in my estimation, I was the world’s worst car salesman.”

When he was laid off,

Cherry didn’t have a nest egg from his playing days.

“People on welfare were getting more than minor league hockey

players in those days,” he said. “I was getting $4,500 for nine years. And in the 10th year, they cut me to $4,200.”

Because of his need

for a job—any job—the stocky defenseman went back to the Rochester Americans at age thirty-seven in the fall of

1971.

“Halfway

through that season, the coach and general manager bailed out because the team had such a rotten record,” Cherry said.

“That’s why they made me the coach. I didn’t get a raise in pay or anything. The next year, I was the general

manager and coach. We took all the players no one else wanted and then made playoffs. The next year, we were the only

independent team in hockey, and we finished first.”

The Bruins hired Cherry in June 1974. In five seasons, he was the

NHL’s coach of the year once and got the Bruins to the Stanley Cup finals twice, and the Bruins lost to the Canadiens

both times. He actually enjoyed the byplay with the media, and he considered his AHL days as his prep course.

“As a general manager , I had to give good press," he told me.

"I really worked at it. The easiest thing about coaching is to coach and then go home. That way, there might be no pressure

on you—not as much, anyway. Let’s face it: I’ve made a lot of enemies. I’ve said a lot of things.

I’ve gotten myself in a lot of hot water. But I don’t regret any of it.”

He brought his beloved wife, Rose, and his famous white pit

bull terrier, Blue, a gift from the Bruins’ players, with him to Denver. He also came with a reputation for sartorial

excellence, and this was before his wardrobe tastes took bizarre turns.

“Honest to God, people used to tune in the TV games just to

see what I was wearing,” he told me of his days in Boston. Cherry said he had “always dressed pretty good. Other

kids would wear sneakers and jeans, but I would wear Oxfords and pants like knickers. And when I was playing, I played for

Joe Crozier, and he used to dress pretty nice. I think the players look up to that. Maybe I go a little overboard.”

The Rockies signed

Cherry to a two-year, $180,000-per-year contract.

“I’m just a guy who likes to go out and have a good time with the players,”

he said. “Somebody asks me how we win so much. It’s the players. First and foremost, everything’s got to

be for the players. If the players aren’t with you, you’re dead. I don’t know; if I knew what I was doing,

I’d probably screw it up.

“I have my own style, and it’s very simple. It’s so simple that [defenseman]

Dennis O’Brien came up to me before a game and asked me to explain my style of game and my philosophy to him. So we

went to a bar, and I drew it on a napkin. It’s as simple as that.” Diagramming that system, he said, it took him

“ten minutes at the most, between sips of beer. Only five, if I’m not drinking beer.”

Cherry immediately was a sensation in Denver. Much of it was his flamboyance, and he

had most members of the media in the palm of his hand. (Including me.) He earned it. He was a dream to cover. He was a great

sound bite for the local television folks, who started showing up at games. I appreciated that he offered colorful quotes,

was always cooperative, and actually enjoyed having a few beers with the scribes on the road occasionally. I was wide-eyed

when he took Fred Pietila of the Rocky Mountain News and me to Toe Blake’s tavern in Montreal and told stories

for a few hours.

The Rockies had the first overall pick in the 1979 draft, an incredible opportunity because four World Hockey Association

teams—-Edmonton (with a teenage Wayne Gretzky), Quebec, Hartford, and Winnipeg-—finally were coming into the NHL.

The two WHA teams that didn’t make the cut and were folding, Cincinnati and Birmingham, also had players who had been

too young to play in the NHL under its previous 20-year-old cutoff, so they were included in the NHL draft pool. Four of Birmingham’s

“Baby Bulls” went in the first round, including defenseman Rob Ramage to the Rockies, the number one choice overall.

Ramage had a solid career, and the consensus at the time was that it was the wise choice. The other Baby Bulls who went in

the first round were Rick Vaive, Craig Hartsburg, and Michel Goulet. Goulet and former Cincinnati Stinger Mike Gartner,

who went to Washington, are in the Hockey Hall of Fame today. So is a young defenseman from the Verdun Eperviers named Raymond

Bourque, who went to Boston in the number eight slot.

Cherry didn’t have the patience for a step-by-step team-building effort. Before long, the

coach was criticizing Miron, both in public and private. Miron acceded to some of Cherry’s requests, acquiring a couple

of veteran players who fit his style. One of the ironies of his stay was that despite his image—cemented during his

days on television—as being suspect of French Canadian players, he was all for the preseason acquisition of Rene Robert

from Buffalo. Robert had been on the Sabres’ famed “French Connection” line, and he quickly became one of

Cherry’s all-time favorites. But the Rockies’ approach was misguided, primarily because they didn’t decide

on a coherent strategy and stick with it. Instead, they were stuck in a no-man’s-land with a hybrid and capricious philosophy,

including periodic attempts to pacify Cherry with the acquisition of hard-working journeymen with more grit than talent or

aging veterans. (Cherry's no-patience mantra actually made sense if the goal was to save the franchise for Denver.)

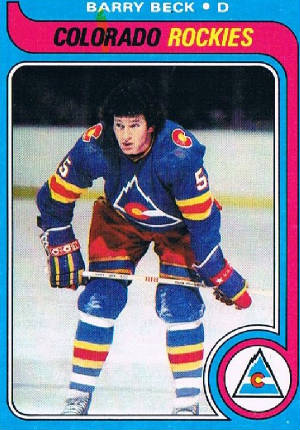

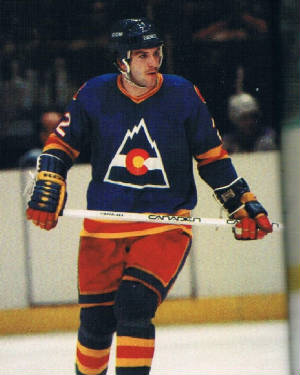

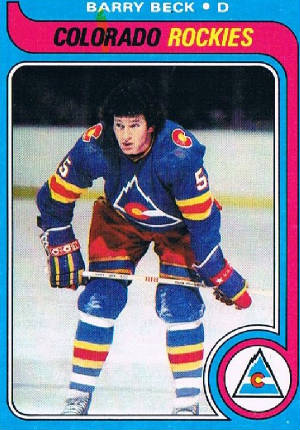

At right, Barry Beck at the

2015 Avalanche game in Denver

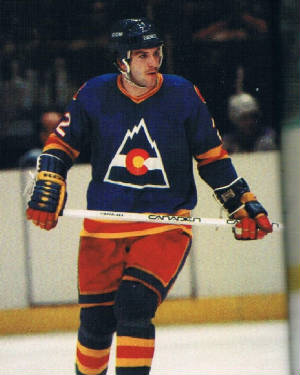

After a 1-7-2 start, the Rockies traded their best young player—intimidating

third-year defenseman Barry Beck -- to the Rangers. He had a booming shot and was the most fearsome fighter in the NHL at

the time. For Beck, the Rockies got a package that included defenseman Mike McEwen and Dean Turner, plus wingers Lucien DeBlois

and Pat Hickey. Shoulder problems later slowed and then ended his career, but trading a young cornerstone defenseman who could

score goals—he had a dynamite shot from the point-—and help shut down opponents was a sign of panic. Cherry publicly

supported the trade, saying that if the Rockies didn’t get some goal scorers, there was no hope.

Years later, when

asked for a "Funny Hockey Memory," Beck told Mark Malinowski of The Hockey News: "Don Cherry’s dog Blue came waddling into our locker room. He came in and, you know how those dogs do it, he

rubbed his butt on the floor – right in front of my locker, in the area I used to do push-ups. So I gave Blue a little

whack with my stick and he ran yelping down the hall back to Don’s office. Then Don came in and asked who did it? We

kind of looked around, said we didn’t know. The next day I got traded to New York. ”

The day the deal was announced—ironically, the day before the Rockies played and beat the Rangers in Denver

with a stunned Beck, a western Canadian boy who was having a home built near Evergreen, going through the motions—I

saw Cherry and Miron walking down the hall in front of me. Cherry actually patted Miron on the back. That might have been

the last time that ever happened. (Beck quickly came to love playing in New York.)

The trade actually made some “sense,” since its ripple effect tied it to the later

deals that brought Lanny McDonald and Chico Resch to the Rockies and at that point, the multiple players acquired improved

the roster as a whole. McEwen, DeBlois and Hickey were bona fide NHL standouts, if not stars. But if the Rockies had kept

Beck, he and Ramage soon would have been one of the league’s elite defensive pairings — and stayed that way for

a long time.

On Nov. 28 in Denver, nearly four weeks after the Beck trade, the Rockies were part of an NHL historic moment —

the first time a goaltender was credited with a goal. A delayed penalty was pending on the Islanders, and Colorado goalie

Bill McKenzie went to the bench. Ramage, who had pinched in, passed back to the point, but no teammate was there and the puck

slid to the other end, into the Rockies’ net. Smith got the goal because he was the last Islander to touch the puck,

but it took a scoring change after the game to get him the goal, and the Islanders already had left the building when the

news broke. The Denver Post was an afternoon paper at the time, and I was astounded when Smith answered the phone

in his hotel room — before charter travel, teams stayed overnight in the road cities after games — and was more

than willing to talk about it. (He might have had some post-game libations by then, I suspect.) He joked that by the time

he could tell his grandchildren about the historic first goaltender goal, he would say he made a spectacular play and a shot

— and nobody would remember enough to contradict him.

A few days later, on Dec. 2, 1979, Cherry returned to Boston Garden

with the Rockies. Incredibly, the Rockies led 4–2 with 53 seconds left. With a faceoff about to take place in the Colorado

zone, the Bruins brought goalie Gilles Gilbert to the bench—and Cherry called a time-out. During the timeout, Cherry

didn’t huddle with the Rockies to talk strategy. He let them rest and get drinks of water. He stepped to the end of

the bench and began signing autographs for the fans who had gathered there; that, of course, brought more fans in their wake.

It was one of the funnier scenes I’ve ever witnessed in sports, in part because it was so brazen. I was just across

the ice, because the hockey press box at the Garden was a front row appendage to the low balcony.

A “Cher-ry, Cher-ry”

chant began and continued through the time-out.

After Colorado had won 5–3 to get to 6–14–3 for the season, Cherry

got in a few digs at his Boston successor, Fred Creighton. He said the Bruins had “as much or more talent as anybody

in the league. There seemed to be an awful lot of times when they weren’t all there.”

The Bruins

still were 15–6–3, but Cherry admonished the Boston press not to forget that the Bruins had gotten off to a 16–2–2

start under him the previous season.

“When

they lost their third game, Blue told me, ‘They can’t match your record for the first twenty games, anyhow.’

Blue is doing handstands all over the place now, I imagine."

Later in December, the Rockies traded Pat Hickey (from the Beck

trade) and Wilf Paiement to Toronto for McDonald and a young defenseman, Joel Quenneville. Although Paiement—the franchise’s

first-ever draft choice when the team was based in Kansas City—was talented, it was a good deal, primarily because cantankerous

Maple Leafs owner Harold Ballard wanted to exile McDonald to Siberia. And that’s what NHL traditionalists thought the

Colorado franchise was at the time.

McDonald was a leader and a terrific player who played with passion and heart, and his bushy mustache

made him hard to miss. Soon, McDonald was the Rockies’ most prominent player ever, and—aside from Cherry—its

most eloquent spokesman. But on the ice, little went well. The goaltending indeed was bad, but probably not as horrific as

potrayed at the timeand especially since. Hardy Astrom, who was acquired from the New York Rangers and making decent money,

was not the worst NHL goalie of all time. A handful of others in the league who played twenty or more games that

season had worse goals-against averages than his 3.75, and there were even a couple who played more than half their teams’

games—Hartford’s John Garrett and Los Angeles’s Mario Lessard. Cherry held his nose long enough to use Astrom—yes,

management and ownership wanted him out there, but Cherry could have defied them—in forty-nine games, while also trying

Bill McKenzie, Michel Plasse, and Bill Oleschuk in the net.

In February, the Rockies had to settle for a 4–4 tie at Hartford

when Plasse had only 17 saves.

Cherry had let loose many times, but he got into high gear that night. “Our goaltending was

horse—-,” he said, standing a few feet from the trailer where I had done a between-periods interview with a fledgling

Connecticut-based cable operation called ESPN. “Let’s face it. Come on. Let’s be honest. We’re not

going to go anywhere until we get a goalie. I’ve tried everyone except the guy who works in the confectionary store.”

I felt as if I were

covering the Washington Generals, the Harlem Globetrotters’ foils and straight men, when the Rockies were the opposition

in the March 1, 1980, game that was “Miracle on Ice” goaltender Jim Craig’s NHL debut for the Atlanta Flames

in the Omni. In Atlanta, the Flames had their first sellout of the season (15,156), everyone waved American flags, and the

Flames probably could have beaten the Rockies using Cherry’s “guy who works in the confectionary store”

as their goaltender. In the story, I said they could have used Eric Heiden, who had just won a big haul of speedskating gold

medals but probably wouldn’t have been helpless in the net. The Rockies’ first shot didn’t come until 12:50

of the first period, and McDonald took it from near the red line. The Flames won 4–1. Craig seemed fazed by only one

thing: the Confederate flag one fan waved behind one goal.

“I’m a Yankee,” Craig said, laughing. “This

has been unbelievable,” he added. “There was the governor’s visit yesterday, and they made me an honorable

colonel of something. I was fortunate enough to have my brother and father here tonight. I just hope they all go like this.”

Surely Craig was on

his way to NHL glory, right? He wasn’t. He wasn’t playing the Rockies every night.

The breaking point in the Cherry

era was the coach’s falling-out in early March with Mike McEwen. Imperatore and Pohan had been Rangers fans and they

liked McEwen. When McEwen stayed out on the ice too long and took an extended shift, and Chicago scored the game-winning goal,

Cherry shook him on the bench. The next day, McEwen skipped practice and he didn’t come to the next game, also at McNichols,

leaving the Rockies with only four defensemen. Cherry was surprisingly conciliatory, saying after that game that he had just

talked with McEwen on the phone and told him he would be welcome back. “What more can I do?” he asked us. “I

made a lot of mistakes when I was his age. Lots of them. I’m not vindictive.”

I also called McEwen (oh, the good old days), and

he agreed with Cherry’s version of the conversation but said he wanted to be traded and wouldn’t go on the team’s

next road trip. McEwen said he couldn’t fit Cherry’s style, so I asked Cherry about that. “Sure he can,”

Cherry said. “That’s what Brad Park thought when he came to Boston, and he was an all star the next year. I don’t

want him to do a lot of things. I just want him to pass the puck a little more. What I’m trying to do is help him. He

thought I was on him all the time. I have an abrasive nature. Some guys respond to it. Some don’t.”

Next, I called Pohan.

“I don’t understand why things reached this point,” he said. I asked him if this was a sign of a deteriorating

relationship between the team and Cherry. “No comment,” Pohan said.

McEwen did come back to the team and finish out

the season.

The incident in Boston when Cherry signed autographs during the timeout was funny. What happened in Denver in late

March was bizarre. The Rockies were playing the Quebec Nordiques when Quebec’s Paul Stewart and Colorado’s Bobby

Schmautz, a former Bruin and one of Cherry’s all-time favorites, drew minors for high-sticking in the first period.

They served their penalties and then were given game misconducts when they waved their sticks at one another in a faceoff.

Before the game could start again, other players raced off the ice—the exits at McNichols were in the corners, across

the ice from the benches—because they had figured out Stewart was chasing after Schmautz in the hallway. So the crowd

was left wondering what was going on as the game was delayed.

Stewart and Schmautz had a brief stick-swinging duel in the hallway between the two locker rooms. Rockies' personnel

told me their team photographer had gotten a shot of the incident in the hallway and I was given a print.

That night, when I went back and forth to talk with the combatants,

Stewart admitted he had gone after Schmautz in the hallway. “I’ve only got two eyes, and I’m not going to

let anyone take a run at them with his stick,” Stewart said. “Hey, even the guys on [Schmautz’s] own team

in Boston said he high-sticked his Thanksgiving turkey to death.”

Schmautz was scornful of Stewart. “This is the guy who came

up earlier this year and got beat up and sat in the penalty box giving the ‘V’ sign because he’d fulfilled

his dream to play in the Boston Garden,” Schmautz said.

By the time the Nordiques became the Colorado Avalanche, Stewart

had found another line of work. He was an NHL referee.

Before the Rockies’ final home game of the season, the players raised their sticks

and formed a cordon for Cherry, wearing a cowboy hat (a gift from the players) and boots, to walk through to the bench. Rene

Robert came into Cherry’s postgame news conference—the Rockies had beaten Pittsburgh 5–0—to explain

the reason for the raised sticks. “It was to show people how much we love him and where he stands in our book,”

Robert said. Robert patted Cherry on the back and headed to the dressing room, and the coach turned to us and said, “Just

like I told you!”

The crowd that night was 11,610, a respectable figure considering we were in the midst of a major spring snowstorm.

“The franchise is here,” Cherry said. “With ten more wins, we’d be in the thick of the playoffs, and

you couldn’t buy a ticket.”

The fans also had chanted Cherry’s name in the final minutes. “Just like

Boston,” Cherry said. “‘Cher-ry, Cher-ry.’ What more can I tell you? There’ll be a lot more

like that. As long as I’ve got the players with me, that’s all I need. You stick with the players, and they’ll

stick with you. The fans love me. The players love me. That’s the most important thing.”

The Rockies finished 19–48–13,

and their 51 points were the lowest in the 21-team league. Their average home attendance was only 9,754, but that was a huge

increase over the average of slightly more than 6,000 the season before. On the ice, the good news was that McDonald, then

only 28, had 25 goals in only 46 games for Colorado and an aura of leadership (and the mustache) that seemed to stamp him

as the franchise’s public face—at least among the players—for years to come.

The day after the season ended,

I called Pohan to do a season wrap-up and casually asked if ownership was considering firing Cherry. Despite the fact that

the strains between ownership and Miron on one side and Cherry on the other were obvious and well documented, I really didn’t

think the Rockies would fire the popular coach. Much to my surprise, Pohan said, yes, he was considering doing just that,

emphasizing it was in the process of evaluating the entire operation, including Miron, as well.

“If we had eighty points right now,” Pohan said,

“I’d put up with anything.”

Cherry dared Pohan to fire him. “If he doesn’t want me back, there’s

nothing I can do about it,” he said. “I intend to fulfill my contract. If not, c’est la vie. I’ve

never backed out on anything yet. I don’t want to leave anything unfinished here. I want to come back. But that’s

up to them. They’re the bosses. I’ll tell you, if you think people have forgotten about me around hockey, let

me give you an illustration. I’m going to go back and film twelve hockey-tip things for Hockey Night in Canada during

the playoffs. They picked five stars from the NHL to do United Way commercials, and I’m one of them. I’ve already

been approached to do five banquets back east in May alone. And you’re asking me if I’m worried about a job?”

Cherry also said he

didn’t think the Rockies were that far off from being contenders; they were heading in the right direction and had made

huge inroads both at the gate and in gaining attention in the marketplace. Looking back, he was right. Again, the mistake

was not going all in on the Cherry approach or patient rebuilding.

It took seven weeks for Pohan to announce his decision.

He fired Cherry. It did take courage, considering Cherry’s support was vocal and widespread. My biggest criticism at

the time was that Cherry’s track record for being uncontrollable and outrageous was well-known when the Rockies went

after him, so they should have known what they were getting.

After

trying to let the furor die down, Pohan had decided that the situation was just too toxic. Imperatore and Pohan deservedly

had the reputation for being great employers in the trucking business, and they expected loyalty in return—not realizing

that professional sports often didn’t work that way.

“He’s said he could get another job in ten minutes,”

Pohan told me. “I’m not going to hold him to that, but. . . .”

Cherry threatened to take a year off, which would

have forced the Rockies to pay him.

He did that work for Hockey Night in Canada in the playoffs, started out as an analyst

the next season, and then was moved into a role that better suited him—the studio pundit’s role on Coach’s

Corner. His ridicule of his Rockies’ goaltender, Astrom, has made the man the former coach calls the “Swedish

Sieve” one of the working definitions for ineptitude in the net—as Mario Mendoza and the “Mendoza Line”

became references to bad hitting. For years, Cherry occasionally belittled Miron, retired and living in the Tulsa area after

making a fortune as one of the founders of the revived Central Hockey League. The CHL eventually awarded its champion the

Ray Miron Presidents Trophy before its folding.

Arthur

Imperatore owned the Rockies only a few months longer after Cherry's firing.

I had lunch with Imperatore and Armand Pohan during the 2003 Stanley Cup Finals at the Imperatore-owned

New York Waterway’s port station in Weehawken.

“We bought that team to bring it here,” Imperatore again acknowledged. “Know

what would happen? Usually, I’d work half the day because I’m a workaholic. I’d get off the airplane, get

a headache first thing. A bad headache. Then I’d get a nosebleed. I’d go the arena and meet the guys and talk

to them about how well we were doing. And then came the clincher. You’re tired, it’d be 9 here when the game started

in Denver, and it’s about to begin, and I’m looking around asking, ‘Where are the fans?’ They’d

come trickling in. All I can see are the empty seats. Then, the game would start, the other team scores the first goal, and

I think of how many more empty seats there are going to be the next game. And, sure enough, that’s what happened.

“I loved that

sport and I enjoyed the experience. But what absolutely confounded me was why the Denver people didn’t take too much

to hockey then.”

Imperatore smiled again and provided his own answer.

“I guess we didn’t have much of a team,” he said.

No, he didn’t.

“In life, you

can’t do everything and do it well,” Imperatore said. “We’re guys who try do something and do it well.

There’s no other way. We tried. We tried.”

To replace Cherry, the Rockies hired Billy MacMillan, a former player and assistant

coach with the then-successful New York Islanders. Miron stayed on as general manager.

On November 30, 1980, the Rockies played at Buffalo.

Pohan attended the game. In the VIP room after the first period at Memorial Auditorium, Sabres owner Seymour Knox introduced

Pohan to Peter Gilbert, a Buffalo cable television magnate and Sabres’ season-ticket holder.

“I have two questions for

you, if I may be blunt,” Gilbert said. “Number one, is your team for sale?”

“Yes,” said Pohan.

“Number two,

how much do you want for it?”

Pohan named his price.

“You’ve got a deal,” Gilbert said. That really was it. Two men shaking

hands.

The news of a tentative deal broke within

days, and the NHL approved the sale in January. I asked Gilbert why it could work under his ownership and not under those

of Vickers and Imperatore. His answer: “We’ll be running it.” He added, “I’ll make people feel

about the Rockies how people in Buffalo feel about the Sabres.

Gilbert

was born in Austria, and he said his family had gotten out of that country in 1933 and made it to British-controlled Palestine.

He joined the British Army late in World War II, served in the Israeli Air Force after the postwar founding of the modern

state of Israel, and moved to the United States in 1950, when he was 24. In a Brooklyn machine shop, he started out as an

office boy and ended up buying the company and turning it into an electrical components company. That company merged with

Alloys Unlimited, and Gilbert made a considerable profit.

In 1970, he bought a bankrupt Long Island cable company from a bank, and it exploded when he talked

Madison Square Garden into awarding his system the rights to Knicks and Rangers games—in the forerunner of the Madison

Square Garden Network. He sold that cable network to Viacom for $12.5 million and reinvested in another struggling cable company,

this one in Buffalo. That also boomed.

So Gilbert had a lot of money to play with, and there was considerable speculation at

the time that he hoped his purchase of the Rockies might help give him the inside track on acquiring the soon-to-be-awarded

exclusive cable franchise in the City and County of Denver or that he planned to make cable a centerpiece of the Rockies’

future. When I asked him about that, he responded, “Let’s not get the cart before the horse.”

I’m convinced

those were the reasons he bought the team. He was a cable pioneer and had a track record in the industry, he knew getting

that Denver cable franchise would be a gold mine, and either separately or in combination, he already had made a ton of money

by being ahead of the curve in utilizing teams as showcases for a regional cable network. (He was thinking of Altitude …

way back then. That’s why he later publicly explored buying the Nuggets, then owned by a large group of mostly local

investors who within a few years sold out to Texan B.J. “Red” McCombs.) But none of those cable plans came together,

or at the very least, Gilbert realized the process would take years.

Late that season, with Gilbert in control of the franchise,

the Rockies finally acquired a good goaltender in a trade with the Islanders. Colorado picked up Glenn “Chico”

Resch and young center Steve Tambellini for Cherry’s favorite, Mike McEwen.

At one point, Gilbert taped television commercials for tickets with McDonald.

In them, Gilbert said to McDonald, “Hey, Lonnie. . .” Nobody had the nerve to correct him, nor saw anything wrong

with putting ads on the air in which the team owner gets his star player’s name wrong. In the macabre and pointed sense

of humor of the locker room, I heard a teammate holler at McDonald at least once a day, “Hey, Lonnie!”

Nothing much changed

under Gilbert, at least on the ice.

In the wake of a fifteen-win season in 1980–81—a season that made the Cherry season

look good—Miron was fired. MacMillan, despite his lack of success as the coach, had impressed Gilbert, and he was championing

the successful model of the “Islanders Way.” MacMillan stepped up to become GM and hired a former Islanders teammate,

Bert Marshall, as head coach, with University of Denver coach Marshall Johnston coming aboard as an assistant coach and assistant

general manager.

I rode with Gilbert on his private plane from Denver to Winnipeg for an exhibition game and got to know him better.

He still was cocky about how he was going to get the franchise turned around, believing if he could do it with two bad cable

companies, he could do it with the Rockies. His bluster wasn’t for everyone. The Rockies’ employees—other

than the players and the famous coach—had been loyal to Imperatore, primarily because Pohan, who was in Denver more,

was universally liked; Gilbert rubbed many of them the wrong way. At one point in the subsequent season, the Rockies played

the Red Wings in the new but already obsolete Joe Louis Arena in Detroit, and I came back to the new Renaissance Center Westin

after the game, realizing that my plan to meet several team employees “in the bar” wasn’t specific enough.

They weren’t in the hotel bar and the “Ren Cen” then had many restaurants with bars in them. As I approached

one of them, though, I could hear a Rockies’ employee blasting Peter Gilbert—“that son of a bitch”—from

the hallway. So I knew my search had ended.

Gilbert hadn’t reacted well to the realization that he had a fiasco on his hands or that he was losing

money by the bushel.

By November,

Lonnie . . . er, Lanny McDonald was refusing to talk to me because he felt I violated a confidence. He came to Denver with

a contract from Toronto that ran through 1982–83, but much of it was based on the assumption he would be playing in

Canada, where he had made a lot of money on endorsements. He also maintained that Imperatore and Pohan had promised him the

deal would be renegotiated after the 1980–81 season if he performed well. I heard that he was asking Gilbert and MacMillan

to honor that commitment, and McDonald said he had no comment on the record but confirmed it off the record and asked me not

to write about it because he expected it to be taken care of quietly and soon. He said he would let me know when that happened.

His agent, Alan Eagleson, initially wouldn’t talk about it, either.

The problem was that the grapevine was hard at work.

It was common enough knowledge and soon I had heard it from enough people to feel as if I had to write about it, and I told

him I was doing so. Then Eagleson, also the head of the Players Association and eventually shown to be a crook, confirmed

it publicly.

McDonald didn’t like it when I wrote about it, and he also was perturbed that I had called Pohan, who said

the promise had been vague and in part designed to react to McDonald’s anger over Cherry’s firing. He said he had told McDonald that the team would consider renegotiating

the contract in the 1981 off-season if McDonald proved he deserved a raise and if the team’s financial condition had

improved. The airing of that dirty laundry didn’t please McDonald, and he gave me the silent treatment for at least

another month. I deserved it; I could have handled it better.

The Rockies reacted by trading McDonald. On November 24, 1981, the

Flames—by then playing in the 8,700-seat Calgary Corral while the Saddledome was under construction next door—blew

out the Rockies 9–2.

The next morning, we went to Winnipeg—and I say “we” because in the fashion of

the time, I traveled with the team on buses to and from airports and on commercial flights. Noticeably, Billy MacMillan and

Bert Marshall weren’t on the team bus to the Calgary airport or on the flight to Winnipeg. Marshall Johnston told me

they were coming on a later flight. I was the only writer on the trip—the Rocky Mountain News was being more

selective about following losing teams—and I asked Johnston if that meant a trade was in the works. He was vague, and

I went to the pay phone and tried both MacMillan and Marshall’s rooms back at the Calgary hotel. They didn’t answer.

At the Winnipeg airport,

McDonald, who was sitting near the back of the plane, was one of the last ones off. An Air Canada agent met Johnston with

a message. As the other players headed for the baggage claim area, I saw Johnston intercept McDonald and take him to a pay

phone. Soon, the other players were all on the bus, waiting, when they noticed that McDonald and Johnston weren’t aboard.

Tambellini (later an NHL general manager) was designated to find out what was going on, and when he went back in the terminal,

he saw Johnston struggling to get his phone credit card number to work and get his call through and McDonald sitting, waiting,

and looking forlorn.

That was Rocky Hockey in a nutshell.

Finally, Johnston reached MacMillan and handed McDonald the phone.

He had been traded

to Calgary, along with a fourth-round draft choice, for Flames forwards Bob MacMillan—Billy’s brother—and

Don Lever. When he got off the phone, he filled in Tambellini, who was noticeably distraught.

McDonald looked at me and said,

“I guess I have to talk to you now.”

His reaction?

“I’m stunned,” he said. “I’m serious. I just can’t

believe it. I think you know I’m not a quitter, that I’d never ask to be traded. All I can say is that I wish

them the very best. I think there are a lot of class guys here.”

We agreed that I’d ride with him in a taxi to the Winnipeg

Arena, where he was going to pick up his equipment, and talk to him there before he headed back to the airport to catch a

flight to Calgary. He boarded the Rockies’ team bus, and he later said in his autobiography that when he broke down

talking to his teammates, Rob Ramage told him to shut up because he would figure out this was the best thing that ever could

have happened to him.

I rode in the cab with McDonald and Rockies’ radio broadcaster Norm Jones to the Winnipeg Arena. Norm and I

both did interviews with McDonald, and Lanny went out of his way to take the high road. “Bitterness has no place in

hockey, as far as I’m concerned,” he told me. “Trades are part of the game. Billy is trying to turn this

franchise around. I don’t agree with him on the trade because I don’t think I was the problem. If you take the

time to feel bitter about every little thing in life, you’re in a pretty sorry state.”

I asked McDonald if his request

for a contract renegotiation was the cause of the trade.

“If it did, they’re crazier than I thought,” he said.

It wasn’t long

before he figured out that Ramage was right. He was a Medicine Hat, Alberta, native. He was going home. But on that day, McDonald

was crushed to be leaving the Rockies. He and his wife, Ardell, truly did love living in Denver.

The trade itself didn’t

seem as ridiculous at the time as it might seem in retrospect—and it especially looked ridiculous when McDonald scored

66 goals for Calgary only two seasons later. Bob MacMillan and Don Lever were solid all-around forwards. MacMillan had 75

goals in a two-season span for the Blues early in his career, and Lever was coming off a 30-goal season. But the fact that

one of the players acquired for the franchise’s most visible and best player was the general manager’s brother

raised a lot of eyebrows, as it should have.

In retrospect, I came to the conclusion that, after all the other trials and tribulations,

Rocky Hockey finally lost any chance of surviving in Denver the day McDonald was traded.

Gilbert barely had owned the team for a year when

it was obvious he didn’t have the stomach for the continued losses. To his credit, he kept writing the checks and the

franchise never was in danger of folding, but at meetings in Washington held in conjunction with the early February All-Star

Game, he officially told the league he wanted to move the Rockies to New Jersey.

That was an issue again because the new Meadowlands

arena finally was on the verge of opening. The meetings went so long and Fred Pietila and I had so much to write that neither

of us made it to the All-Star Game itself.

The league put Gilbert on notice that at the very least, he had to exhaust all avenues

in finding a buyer who would keep the team in Denver.

In the final month of the season, there was a brief glimmer

of hope.

As the Rockies struggled

to survive, young defenseman

Joel

Quenneville was one of their most promising players. (Rockies media guide)

A St. Louis high-risk insurance

mogul met with Gilbert and was championed as a possible owner by a Colorado-based member of the Rockies’ board of directors—a

group that was largely window dressing as Gilbert attempted to defuse the issue of absentee ownership. One day, though, I

took a call from St. Louis, and the caller outlined how I could check out two of the mogul’s companies. With a lot of

help from folks in the Missouri Secretary of State’s office and other sources, I ended up with mountains of material

about the companies and lawsuits and about the Missouri Division of Insurance accusing one of the companies of misappropriating

$166,595 in premiums. I also came up with photocopies of two $150,000 checks to a lawsuit plaintiff that bounced.

And this guy was going

to buy the Rockies?

I went to St. Louis and visited the insurance mogul at his offices, and he was cordial, downplaying the significance

of the checks and saying he still was interested in buying the Rockies. I wrote smaller news stories about all of these findings

and had a major Sunday package, including a question-and-answer piece with the mogul, ready for publication when he sent a

telegram to Gilbert and the Rockies “withdrawing” his offer.

We still ran the Sunday package on March 28, 1982, including a picture

of one of the bounced checks, under the headline: “The Man Who Almost Bought the Rockies.” That probably wasn’t

accurate, though. It was obvious to me that he never would have been able to pull off the purchase. Even if I hadn’t

written a word about his business dealings, that still would have been the case. So I never felt that I had anything to do

with “scuttling” a deal.

But it all was so Rocky Hockey.

The goalie nobody called "Glenn." He was "Chico."

(Rockies

media guide)

The Rockies beat the Flames 3–1 in the final home game of the season at McNichols.

Resch was the number one star. By then, most NHL observers assumed the franchise was leaving, but Resch said, “I’d

just like to thank the fans who came out and the ones who thought about coming out but didn’t. We gave them a lot of

reasons not to. We think we can improve next year. If people will have a lot of faith and maybe buy season tickets.”

I talked more about Rocky Hockey

with Resch years later, when he was a Devils broadcaster. “In this league, if you said you survived “Rocky Hockey,’

that means you went above and beyond,” he said. “You could get through any blizzard of life if you got through

that. It’s not that it was all bad, but the toughest part was just the uncertainty. There never was a commitment for

a four- or five-year plan. There wasn’t even a four- or five-month plan. It was a four- or five-day plan. The fans that

came were very good. We always thought we were one win from getting it going. But you know, it’s really nice to know

it was the hockey town we all thought it was. Unfortunately, it just took longer than we would have liked.”

It was too late. Edmonton furniture and real estate magnate

Bill Comrie was the major figure in a group that talked about buying 70 percent of the franchise with local ownership retaining

the remaining 30 percent. That deal also fell apart and for a bizarre reason. With the deal under discussion in mid-April,

an armed intruder burst into the home of Edmonton Oilers owner Peter Pocklington, who was trying to broker the sale, and demanded

$1 million in ransom. Police eventually shot the extortionist, but Pocklington was grazed in the arm in the crossfire. Shaken,

he had better things to do than to help close the sale that would have kept the Rockies in Colorado.

At least I got a couple of trips

to New York out of it. In mid-May, the NHL’s board of governors met for two days in Manhattan, failing to agree on the

Rockies’ fate or what to do with the Meadowlands market. Gilbert proposed simply being allowed to move the Rockies there,

but it was obvious the NHL wasn’t going to allow that to happen. Millionaire John McMullen wanted either the Rockies

or an expansion team for the Meadowlands, and the debate mostly revolved around how the league could allow the Rockies to

go New Jersey and still get the same amount of money it would get from expansion fees if an expansion team went there. Every

time Gilbert walked out of the room, I was in the mob chasing him down for comment, even if he was just taking a restroom

break. Part of the comedy was that he was willing talk to me on the phone from his Buffalo home or in his hotel room at these

sorts of meetings, whether it was an official on-the-record comment or a background briefing. So I was part of the mob out

of self-defense more than anything else.

When the meetings adjourned, board of governors chairman Bill Wirtz—who I have

to say was always helpful to me, despite his spendthrift and curmudgeonly image as the Blackhawks’ owner—confirmed

that there wasn’t anything under discussion that would keep the Rockies in Denver. Gilbert said the same thing. I marveled

at how quickly he had gone from being the blustery self-professed savior of the NHL for Denver and even a possible buyer of

the Nuggets to a harried, even hapless man trying to get out without losing his shirt.

The official end came at another meeting in New

York on May 27, 1982.

The league approved Gilbert’s sale of the Rockies to McMullen, who at the time also owned the Houston Astros,

and two minority partners—Brendan Byrne, former New Jersey governor, and John Whitehead, senior partner of Goldman Sachs.

The league also approved a franchise shift to New Jersey.

Because it wouldn’t be getting an expansion fee for the New

Jersey territory, the NHL forced McMullen to pay compensation to the New York Rangers and Islanders and the Philadelphia Flyers;

he also had to pay a transfer fee to the league. Gilbert, who had paid $7.6 million for the team, got $10 million.

He said the franchise

losses were greater than his profit on the sale. In announcing the league approval of the moves, NHL President John Ziegler

said the league tried to come up with owners to keep the team in Denver but failed. “To operate the team in Colorado,

based on the financial record, someone would have to be willing to lose a lot of money until the team was turned around,”

he said.

The day after the league’s board of governors approved the sale and move of the franchise, I went to the Meadowlands

on the other side of the Lincoln Tunnel for the news conference at the new arena. Everyone involved predicted the NHL immediately

would be a hot ticket in New Jersey, and we’d see such phenomena as season ticket rights being fought over in divorce

proceedings and passed on through wills. New Jersey Governor Thomas Kean put it this way: “I can assure the management

as well as the players that the seats in this arena will be filled game after game.”

McMullen said that sounded good

to him.

“I’m

convinced the stadium will be filled every evening,” he said.

In reality, the Devils would “underachieve” at the gate,

even after Lou Lamoriello had taken over as general manager and built the franchise into one of the league’s elite teams.

Back in Denver, we

were left to wonder if we’d ever get another shot at the NHL.

* * *

ADDENDUM:

Many former Rockies later got into coaching, scouting, broadcasting or front offices,

so I ran into many of them over the years. One of them, of course, was Avalanche coach Joel Quenneville. Resch has returned

to Denver many times as Devils broadcaster.

"In this league, if you said you survived "Rocky Hockey,' that means you went above and beyond,"

Resch told me. "You could get through

any blizzard of life if you got through that. It's not that it was all bad, but the toughest part was just the uncertainty.

There never was a commitment for a four- or five-year plan. There wasn't even a four- or five-month plan. It was a four- or

five-day plan.

"The fans that came were

very good. We always thought we were one win from getting it going. But you know, it's really nice to know it was the hockey

town we all thought it was. Unfortunately, it just took longer than we would have liked."

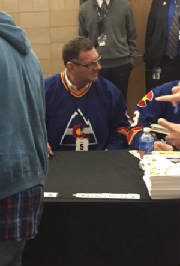

In 2015, as noted in the picture captions above, the Avalanche brought in several former

Rockies for an appearance at an Avalanche-Blue Jackets game at the Pepsi Center. They signed autographs for a long line of

fans on the main concourse.

I spoke with a few

of them, both saying hi and asking how they looked back at Rocky Hockey.

"We absolutely had the greatest time when we played here,"

Lanny McDonald said. "Unfortunately, we weren't as good as the Avalanche was. But the bottom line was there was about

8,000 great hockey fans that showed up every night. We just needed to be a .500 hockey club and it would have been here forever.

But times change, things change and it's great to have a chance to come back after all these years."

I asked Barry Beck about his his years-later perspective about his trade to the Rangers.

"My life completely changed at that point," Beck said. "I was really hurt by that. We had a good young

team, and I thought we could get a lot accomplished here. It was nice to see when the Avalanche came here they won right away

so the fans didn't have to wait long. But all the Rockies players were proud of that team and thought we were going places."

The franchise, at least, indeed went places --

to New Jersey.

Terry Frei's web site