|

THE PARC 55 HOTEL IN SAN FRANCISCO’S Union

Square was thirty-two stories tall, and my room was near the top. I walked down the stairway and outside. On Market

Street, one of the first things I noticed was the clock in front of Samuels Jewelers. Both faces of the pillar clock

were frozen at 5:04. A plaque touted it as “one of the finest street clocks in America” and pointed out that

it was “insured by Lloyd’s of London.” I wondered if the policy still was in force. A few steps away,

a man wore a sandwich board sign that proclaimed: “Fallen, fallen is Babylon.” He would not tell me his name

or even speak. It was the morning of October 18, 1989—the morning after the Loma Prieta earthquake. It also

was the morning after Game 3 of the World Series between the Oakland Athletics and the San Francisco Giants was supposed to

have been played at Candlestick Park. After the Athletics romped 5–1 in Game 2 on Sunday, October 15, taking a

2–0 series lead, I noted in my column that they seemed on the verge of ignoring manager Tony La Russa’s suggestion

that they remain low key and to avoid waking the sleeping Giants. Rickey Henderson stole bases after the game was

decided, Dave Parker’s home run trot was turtlelike and taunting, and Jose Canseco—remember, this was before

he started naming names and when the A’s Mark McGwire was a rail compared to what he would become in later

years—was strutting everywhere he went. At least reliever Dennis Eckersley, who had served up the infamous home run pitch

to the Dodgers’ Kirk Gibson in Game 1 of Los Angeles’s five-game victory the year before, was being cautious.

He noted that he was on a Chicago Cubs team that blew the 1984 National League Championship Series after taking

a 2–0 lead over the Padres. “I’ve trained myself not to get too carried away,” he said after

closing out Game 2. “I’ve played too long and know that anything can happen.” Anything could

happen. Even an earthquake. Two days later, after

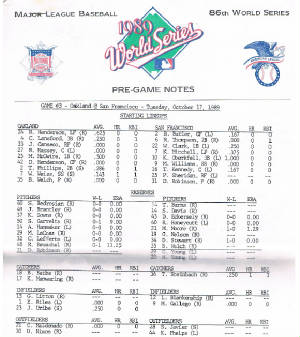

the routine interviews on the field before Game 3, we retreated to the press boxes. The regular baseball press box—especially at

Candlestick at the time—was far too small to accommodate all of the credentialed writers, and those spots went

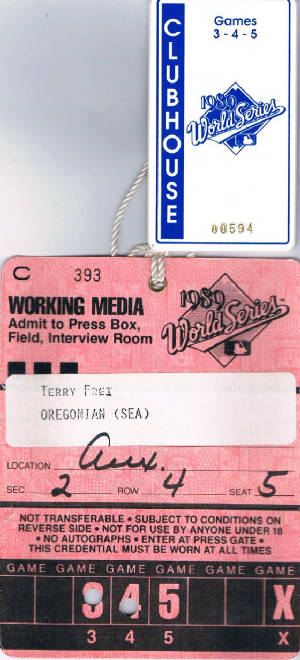

mostly to the beat writers of specific major league teams. Although I was a Professional Baseball Writers of America

member and went to many Seattle Mariners games and also made a couple trips a year to do columns on both the Giants and

the Athletics, I joined others in the temporary auxiliary press box constructed in the first rows of the upper deck.

It wasn’t a bad vantage point, and I was looking forward to watching the games from there. Some background notes to put the following in context. This was long before cell phones were part of everyday

life. We would be rushing to beat the newspaper deadline, so like many writers, I had arranged through the telephone

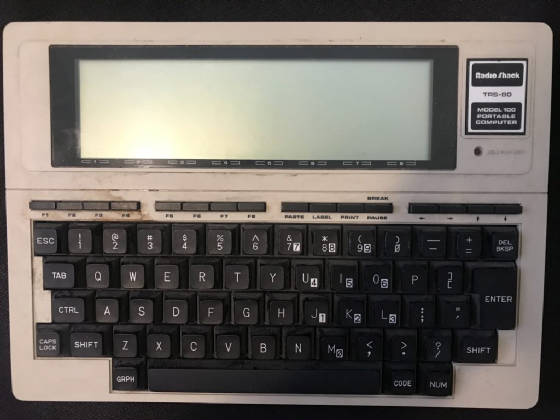

company to have my own line and phone installed at my seat. My computer was typical for the time: it was a tiny Radio Shack TRS-80, the infamous “Trash 80”

that operated on either an AC adapter or (and this would become important) AA batteries. It had a tiny four-line screen

and transmitted to the newspaper via a phone call. If the telephone cord was modular and could be removed from the

phone, we could transmit easily and quickly through the phone line. If it was a pay phone that didn’t have modular

connections, we had to jam each end of the handset into coupler cups. That worked roughly 41 percent of the time and

often led to chunks of copy disappearing. I had a portable radio that could get television sound, too.

When the stadium shook, the reporter next to me, Shannon Fears—a Bay area native—knew what it was.

He jumped up and was ready to move. Initially, I just sat there. Over the next few hours, as did many of my brethren,

I talked with fans in the stands and on the walk back to the media bus. I wrote with that tiny Radio Shack on my

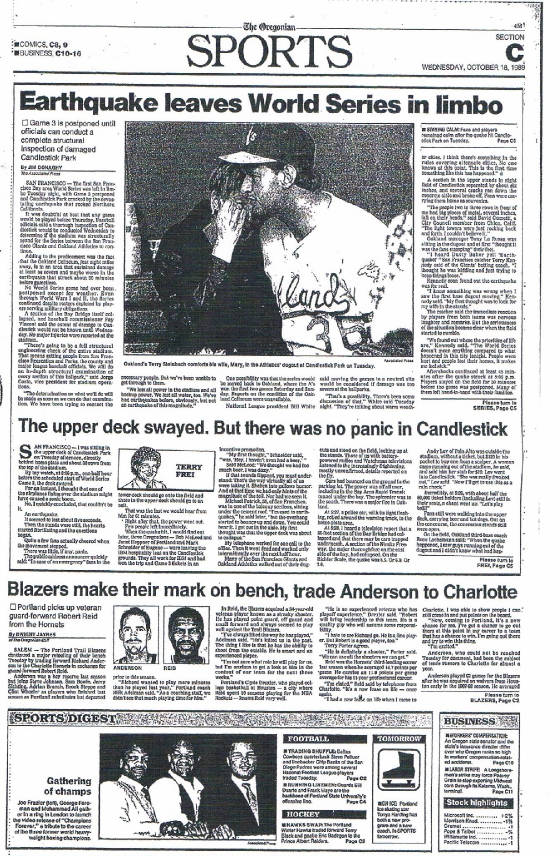

lap as the bus crawled back to downtown San Francisco. Here’s the column that appeared the next morning in the Oregonian. I have

resisted the urge to touch it up (I have been teased that my modifiers often aren’t just dangling, they are on

opposite coasts from the words they modify), and it is word-for-word what landed on the porches the next morning.

Even many years later, I’m amazed that it actually made it into print. I must have had fresh batteries in that

Trash 80. SAN FRANCISCO—I was sitting in the upper deck of Candlestick Park on Tuesday

afternoon, directly behind home plate and about 30 rows from the top of the stadium. By my

watch, at 5:05 p.m., one-half hour before the scheduled start of World Series Game 3, the deck swayed. For an

instant, I thought that one of the airplanes flying over the stadium might have caused a sonic boom. No, I

quickly concluded, that couldn’t be it. An earthquake. It seemed to last about five seconds. Then the stands

were still, the hearts started fibrillating and the questions began. Quite a few fans

actually cheered when the movement stopped. There was little, if any, panic. The public-address announcer

quickly said: “In case of an emergency” fans in the lower deck should go onto the field and those

in the upper deck should go to an exit. That was the last we would hear from him for 61 minutes. Right

after that, the power went out. Few people left immediately. When the quake hit, I would

find out later, three Oregonians—Bob McLeod and Janet Heppner of Portland and Mark Schneider of Eugene—were

leaving the IBM hospitality tent on the Candlestick grounds. They all work for IBM and had won

the trip and Game 3 tickets in an incentive program. “My first thought,” Schneider said, “was, ‘Hey, I haven’t

even had a beer.’” Said McLeod: “We thought we had too much beer. I was dizzy.” If that

sounds flippant, you must understand: That’s the way virtually all of us were taking it. Shaken into gallows

humor. And at that time we had only hints of the magnitude of the toll. Nor had we seen it. Michael

Patrick, 38, of San Francisco, was in one of the balcony sections, sitting under the cement roof. “I’m

used to earthquakes,” he said later, “but the overhang started to bounce up and down. You could

hear it. I got out in the aisle. My first thought was that the upper deck was about to collapse.”

My telephone

worked for one call to the office. Then it went dead and worked only intermittently over the next half hour. Many

of the San Francisco Giants and Oakland Athletics walked out of their dugouts and stood on the field, looking

up at the stands. Those of us with battery-powered radios and Watchman televisions listened to the increasingly frightening,

imostly unconfirmed, details reported on the fly. Cars had bounced on the ground in the parking lot. The power was off all over,

including in the Bay Area Rapid Transit tunnel under the bay. The epicenter was to the south. There was a major

fire in Oakland. At 5:27, a police car, with its lights flashing, rolled around the warning track, to

the home-plate area. At 5:28, I heard a television report that a 50-foot section of the Bay Bridge had

collapsed and that there may be cars trapped underneath. A section of the Nimitz Freeway, the major thoroughfare

on the east side of the bay, had collapsed. On the Richter Scale, the quake was 6.5. Or 6.9. Or 7.0. Andy

Lev of Palo Alto was outside the stadium, without a ticket, but $120 in his pocket to buy one from a scalper.

A woman came running out of the stadium, he said, and sold him her stub for $10. Lev went into Candlestick.

“She was really freaked out,” Lev said. “Now I’ll get to use this as a rain check.” Incredibly,

at 5:39, with about half the 60,000 ticket holders (including Lev) still in their seats, a chant went up. “Let’s

play ball!” Fans still were walking into the upper deck, carrying beer and hot dogs. Out on

the concourse, the concession stands still were open. On the field, Oakland third-base coach Rene Lachemann said: “When the quake

happened, I saw guys running out of the dugout and I didn’t know what had happened. I thought there might

be skydivers landing or something. Now I don’t know how we’re going to get back to Oakland.” At 5:41,

there was a mild aftershock. The upper deck had moved slightly again. At 5:43, the players who had remained

on the field gathered up their families and walked toward the clubhouse door in the right-field corner. Ushers

remained on duty, directing traffic. But it wasn’t a rush of panic, only general milling. At 6:05,

a man with a bullhorn stood on the field and told the remaining fans to evacuate the stadium “in an orderly

fashion.” One minute later, the power was restored—at last long enough for the public-address announcer

to tell everyone to leave. U.S. Highway 101 was within sight from the concourse and traffic seemed to be

moving. However, few vehicles were getting out of the parking lot. The upper concourse concessions stands

still were open. And the souvenir stands were doing brisk business. More than once I head a variation of: “These things

are going to be collectors’ items.” We walked to the media bus. Again, there wasn’t much panic. Just concern. I’m writing this on a bus riding through darkened streets, hoping to be able to transmit when we make it to the first downtown stop, the Meridien Hotel. One man

on the bus just got ill. “Be extremely careful,” the bus driver just said. “They are doing

a lot of looting down here. So be careful.” Update: Sixty-three minutes after the

bus started moving, we pulled up at the Meridien. The lobby was dark, but the bar was open and cocktail waitresses

were serving drinks. Th e makeshift pressroom was open in a restaurant. If you’re

reading this, the phone worked. After filing the column and probably having a drink at the Pierre Restaurant,

the temporary media work room in the Meridien, I walked a mile through the darkened downtown—three blocks down

Battery Street and then the rest of the way on Market to the Parc 55. The power was out, but a freight elevator

and hallway lights were operating on a backup generator. I waited my turn to ride upstairs. On my floor, the darkness was

eerie. Most of my fellow guests had their doors propped open to let the limited light from the hallway into the room.

The two women in the room next to me were from Missouri, as I recall, and we talked briefly, yet I never saw them.

I managed to get ready for bed in the dark and went to sleep. The next morning, I did a radio interview by phone with Scott Lynn of Portland’s

top station, KEX. I heard announcements in multiple languages through the hotel speaker system about where food and other necessities

were available. I left and after noticing the Samuels Jewelers clock and the man with the “Babylon” sign,

wandered through downtown feeling a bit guilty because authorities were asking residents to stay put if at all possible. Traffic moved

fitfully without signals. Stores and restaurants were closed. All of them, that is, except for the South of Market grocery

on the corner of Fourth and Howard, across the street from the George Moscone Convention Center. Inside the small

store, a rack of snack food had collapsed, so packages of Lay’s Potato Chips littered one aisle. Beer and soft

drinks still were cold in the dark refrigerated cases, but bottled water, orange juice, and packaged food were the

best sellers. A line of about ten people went up one aisle as manager Abe Bateh added up prices with a pen on brown

bags. He rounded off prices to avoid using coins, but the prices were near their original levels. He was not gouging his

customers. “Nobody told me to open,” Bateh told me. “I came here and when everybody was here

and hungry, I decided to open.” Across the street at the Convention Center, a two-tiered social drama was playing

out as engineers from around the country who were attending a water-pollution conference mixed with the refugees from

the nearby Tenderloin district who had been forced out of their apartments and the hotels catering to transients

by the quake’s effects. Inside the door, a sign directed the homeless and stranded downstairs to the makeshift

American Red Cross disaster center in the exhibit hall. Rodney Bacon, a Red Cross volunteer, told engineers that

their conference was canceled. When the bedraggled walked in the door, Bacon pointed downstairs. Franklin Schutz,

an engineer at West Virginia University in Morgantown, wasn’t sure when he would be getting home. But he said he

had spent the night in his low-rise Cow Hollow hotel in the decimated Marina District. “It was sort of like

a block party,” he said. “The buses were running. One Mexican restaurant was serving on paper plates for

anyone who walked up. When I tried to use a coin phone, somebody walked up and held a light for me so I could see.

A lot of people had portable radios.” When Schutz got through to his wife in West Virginia, he told her how he had been

on a bus outside the convention center when the quake hit. “We were wondering who was fooling around with the bus,”

he said. In the exposition hall downstairs, men and women slept on cots, sat silently, or milled around and quietly talked.

Steve Hull, a Red Cross volunteer supervisor, told me that “between 350 and 500 people” spent the night

in the center. He said the Red Cross served breakfast to more than 800 from the Tenderloin District and that they had

been told they could stay as long as “four or five days.” Barbara Egar, who was staying in a nearby apartment

until her gas and electricity went out, sat in a chair against one wall, her arms wrapped around her knees. “It

was weird here last night,” she told me. “Weird people. They were threatening, too, at times. It was abusive

language, the grossest stuff you’ve ever heard.” I asked her if she slept. “No,” she said. “No.

Too many weird people.” Even before the quake, she said, she was planning on returning to her former home

in Arkansas. “I don’t have any money to go home on now, though, to tell you the truth.” Twenita Jones,

thirty-two, was five months pregnant. When the quake hit, she was at the Episcopal Center shelter, four blocks away from

the convention center. “We were getting ready to eat,” she said. “The floors and everything were

moving and when it stopped, they sent us out in the parking lot. When the aftershocks came, they took us out of the building

again. We stayed there in the dark last night, then they brought us here at 6:30 this morning.” Jones said she

had been at the Episcopal Center for only three days after leaving her apartment building because she couldn’t

pay the rent until her next Aid to Families with Dependent Children check arrived. “Now I’m just waiting

to get something to eat,” she said. At midmorning, the homeless still filtered into the exposition hall.

They signed a sheet at the door. Some carried packs and clothes. Others had nothing. A slight, bent

man with a gray-speckled beard spotted my open notebook and the World Series media credential hanging around my neck. He

approached me with both hands in his pockets and a not-so-shy smile on his face. “You should talk to me,”

he said. “I was one of the best lightweight fighters in the state of California. Everybody knows me around here.” He said he was

Oscar Smith, a sixty-six-year-old retired construction worker who once had fists of brick and fought out of Newman Gym.

“I fought all the good fighters,” he said. “I fought for Johnny Monroe. I was a stablemate of

Earl Turner.” Surely I knew those names, he told me. Well, no, I didn’t.

But when Oscar couldn’t

tell me his record, we were even. “I don’t know,” he said, “but it was good.” When I checked

later, he wasn’t listed in the sports department’s oldest Ring Record Book, the 1960 volume, but that didn’t

mean he was pulling my leg. Oscar said he was a refugee from the Angelo Hotel on 6th Street. He told me he

had been staggering between the ropes in recent years, living on social security and assistance checks totaling $667

a month. He said he had lived in another hotel with a transient clientele for fourteen years, “until they put me out on the street because of a mistake” five

days earlier. “They said I hadn’t paid the rent, but I had,” he said. “That’s the God’s truth.

The landlord must have gone south with it. I think they just wanted to get me out because they could rent the room for

more money from somebody else than I was paying.” After being evicted, Oscar moved into room 331 of the Angelo. He told me that

on the day of the earthquake, he was working underneath a friend’s car on Eddy Street, near the hotel. “The

car was wheeling and rocking,” Oscar said. “I thought somebody was rocking the car, jumping on the running board. As soon as I got out from under the car and they told me what had happened,

I was frightened to death.” He said the Angelo shut down completely. “Th ere was a housing authority cop

or somebody like that standing out front, keeping us out,” he said. Oscar said he managed to sneak back into his

room “before they came and knocked in the door and told me to get the hell out of there. They said the building was

condemned. So I came here. They gave us sandwiches and coffee, and they were real nice to us.” A pregnant woman

approached us. “This is my pal,” she said, putting her arms around Oscar’s neck from behind. “It

was pitch-dark and I was one of the last ones out of the hotel. It was so dark and I told this nice gentleman I needed

some help. And do you know that he put his hand out to me and I had to slap him silly?” They both laughed

and the woman, who declined to give her name, walked away. Eventually, so did I. That night, I attended Commissioner

Fay Vincent’s news conference in a meeting room at the Westin St. Francis. The only lighting was from candles

and the limited number of makeshift television lights. The rumors had flown all day about such alternatives for the World

Series as finishing in Los Angeles and Anaheim, moving it back across the bay to Oakland for all remaining games,

or canceling the rest of the Series altogether. Vincent did the sensible thing, saying Major League Baseball would put

the Series on hold until at least the next Tuesday, one week after the earthquake. That seems an obvious decision

in retrospect, but at the time there was a lot of that knee-jerk “puts-things-in-perspective” rhetoric flying,

and if Vincent had announced the Series was canceled and blathered on about baseball knowing its place, he would

have received widespread praise. I caught a flight home in the next couple of days and was in Portland when the

Giants visited the refugees at the Moscone Convention Center after a Friday workout. None of the stories featured my

buddy Oscar. I returned the next week, after Vincent announced that the Series would resume on Friday, October

27. The Athletics finished their four-game sweep with consecutive

victories at Candlestick. The incident I most remember during the resumption of the Series came in the bottom of the

ninth inning of the A’s 13–7 win in Game 3.

The Giants’ Candy Maldonado was at the plate,

and we were merely counting down the pitches until it was over. Suddenly, one bank of lights in right-centerfield went

dark. As the umpires and others began considering what to do, a single light appeared in the section below the bank.

It might have been an usher with a flashlight. It could have been a single fan with a lighter. Then there were five

lights. Then, faster than you could follow the progress, there were hundreds around the park, far beyond the affected

area, individual lights from flashlights, butane lighters, matches. Amid laughter and bobbing points of light, the

game went on. At that point, what were a few light bulbs? The Series ended on a day when banners in downtown San Francisco heralded “Quake

Sales,” “Earth-Shaking Bargains,” and “Giant Reductions.”

Souvenir emporiums couldn’t

restock tables with “I Survived the Quake” Tshirts fast enough. I still have mine. The dead were

not forgotten. Neither were the sensations of loss and helplessness and horror. It was appropriate to remember, yet time

to move on. At least in baseball.

|