I presented the introductory piece below to my journalism classes at Metropolitan

State University of Denver.

As we begin the semester, I'm going to take you back to when I, generally speaking, was your age. See if you can

identify with any of this.

(Don't wince. I won't ask you to get off my lawn.)

My first two published

stories were in my high school's newspaper -- South Eugene's award-winning The Axe. I was 16.

At the time, my father,

Jerry, was the head football coach at the University of Oregon. He wound up serving on the Ducks' staff for a total of 17

years before he moved to Denver as the Broncos' offensive line coach. He didn't include it in his coaching biography, but

he was a decorated P-38 fighter pilot in World War II, flying 67 missions in the unarmed one-man plane to go over enemy targets

and take reconnaissance photos in advance of the bombing runs.

As my junior year approached, I knew I wouldn't be

playing football for the South Eugene Axemen because of knee surgery. I had time on my hands. I enrolled in an introductory

journalism class. I was not on The Axe staff -- it was mostly seniors -- but the newspaper adviser was teaching the course

and our stories were fair game for the paper to run.

This was a long time ago, but I believe only those

two stories made it into The Axe.

Yes, the son of the high-profile Ducks' football coach and World War II

vet wrote two stories about the Vietnam Veterans Against The War.

For the first piece in October, I attended a

Lane County VVAW assembly and open forum in downtown Eugene. My favorite disc jockey was a Vietnam vet and had plugged the

event on the air. A handful of vets spoke, and I noted: "...a sparse, but captivated crowd heard the veterans speak of

the atrocities of war, some of which [they argued], fell under the category of war crimes." The story was amazingly graphic,

especially for a high school paper.

The next month, I went to the U of O's student union to hear the VVAW's

one-time leader, a 27-year old Navy veteran named John Kerry. Yes, that John

Kerry. The almost-president and Secretary of State John Kerry. I quoted him to open the story: "The veterans went off

to fight in the name of their country. But now, after being there and seeing what it was all for, we are once again acting

in the name of our country -- to stop the war."

He went on from there. My story again was far from objective. But it was dreadful. When I post it on my web site, I usually cut it off, showing as little

of the story as I can. I wish someone had told me to gas the dreaded "quote lede" and a bunch of wince-inducing

cliches. The headline was, "Veteran leader blasts war policies" and "Vietnam 'tragic' mistake." At the

end, I noted he asked the Vietnam vets in the audience to come up and "rap." I stood on the fringe, away from the

group, but close enough to watch and listen. I might have shaken Kerry' hand. I admit I don't remember if I did or not.

My stories would have been much better if I had more closely scrutinized the material and done

more -- or any -- legwork. I wasn't on deadline. I'm proud of the stories as they turned out, especially given my age, but

they could have been better. I also know I had factual errors in the piece. That's never acceptable. I won't go over them

here. They're there, though.

I continued my anti-Vietnam War activism in my year and a half at Wheat Ridge High after we moved to the Denver area

three months after my Kerry story ran.

In the summer after my freshman year at CU, I wasn't yet in the Journalism

School, but I already was working part-time at the sports department of Denver's Rocky Mountain News. In the summers, as it

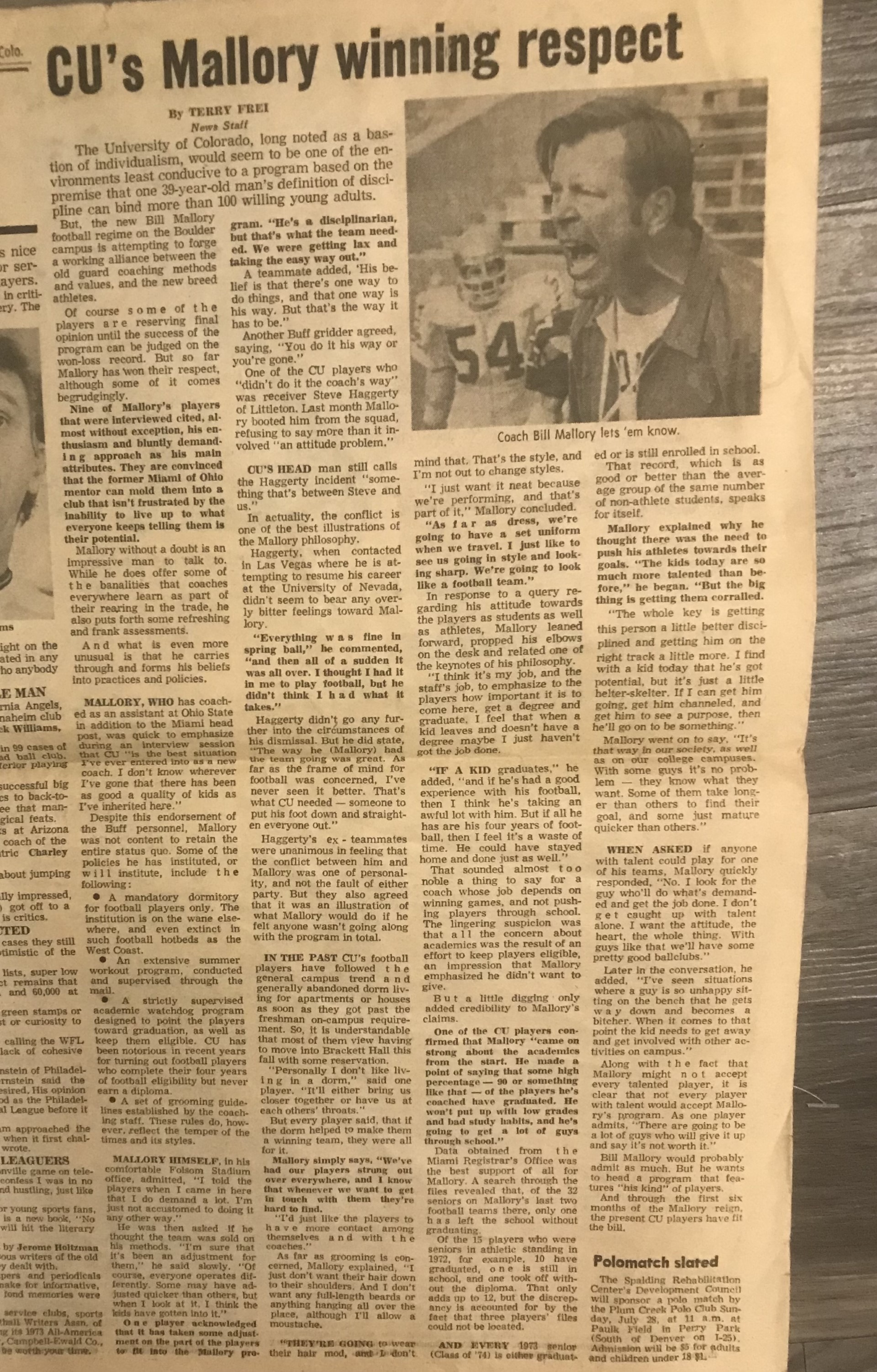

turned out, I was full-time, essentially operating as a vacation fill-in. I talked editors into letting me do an extensive

portrait of Bill Mallory, CU's first-year head football coach. The angle: Mallory said all the right things about expecting

players to take school seriously and graduate and about running a "clean" program, something CU hadn't always done.

Did Mallory mean it? He also instituted some what I considered to be silly rules about grooming and hair length, equating

it to "discipline." Yes, in Boulder.

I interviewed Mallory at length. I was 19, three years

older than when I wrote about Kerry and the VVAW. In general, I was what your age is now. I was sitting across the desk of

a well-known football coach, which perhaps wasn't intimidating for me because of my own father's background. I disagreed with

some of Mallory's standards and wondered if he was a good fit for Boulder (as it turned out, he wasn't), but I was impressed

by his sincerity and I liked him. I quoted him extensively in the eventual July 14, 1974 News story.

story. Also, I lazily quoted several players anonymously with their comments about the new CU coach after spring practice.

(This was the Watergate investigation period; at least I didn't call one of my sources "Deep Throat.") Several players

were critical of their new coach.

I also contacted the registrar's office at Mallory's previous head-coaching

stop, Miami of Ohio. Privacy standards were be tightened in ensuing years, despite passage of sunshine legislation. I found

a helpful woman in the office, and I provided her a list of Miami players to check on.

This, from the story:

"Data obtained from the Miami Registrar's Office was the best support of all for Mallory. A search through the files

revealed that, of the 32 seniors on Mallory's last two football teams, only one has left school without graduating. Of the

15 players in athletic standing in 1972, for example, 10 have graduated, one is still in school and one took off without a

diploma. That only adds up to 12, but the discrepancy is accounted for by the fact that three players' files could not be

located."

In gratitude, I sent flowers to the woman in the Miami registrar's office.

Don't

ever, ever do that.

I repeat: Don't ever, ever do that.

I was chagrined later when I realized I should have tried to determine how many underclassmen

had left the program, and maybe at least wondered where the hell those seniors' files went. I'm not suggesting anything untoward;

I'm saying my search was flawed because I left too many questions unanswered or even un-posed.

I didn't

find any smoking guns. Not even when I for several days wrote down the license numbers of cars parked at Brackett Hall, which

had become a mandatory football dormitory under Mallory, who unapologetically said he wanted the staff to be able to keep

tabs on the CU players. I foggily remember getting printouts with the ownership information, and I assume it was from

Departments of Motor Vehicles. Nothing jumped out. As near as I could tell, all the cars were registered to the players or

family members. This was before NIL.

In late 1975, still with the Rocky Mountain News, I also tackled

a Colorado story that had become notorious nationally.

In tiny Eads, Colorado, a young high school girl had gotten pregnant and married

her boyfriend, the father. She was a promising basketball player, but wasn't allowed to play as a sophomore and junior because

of a rule that banned married students from participating in sports. But she then filed a suit contesting the rule, hoping

to play in the first-ever girls' state basketball tournament in the 1975-76 season. The fight created a schism in the little

town. I interviewed both the girl and her husband, and a touching picture of the girl wearing her letter jacket and posing

with her young son ran with the eventual story. It was a good story, played as the lead piece in the sports section. The flaw?

I spoke with several girls who would have been her teammates and allowed a couple of the most critical to be anonymous in

the story. It was unfortunate. The girl had her supporters, too, and -- surprise -- they were fine with me using their names.

the legal fight dragged out, and she didn't play as a senior, either.

(An aside: Years later, I tracked down the "young

girl." It wasn't easy. Her original name was a matter of public record, of course, but she had been divorced and remarried.

With some help, I found her. She was the president of a bank. I asked if I could do a follow-up story with her, highlighting

her success. She politely declined and asked me not to press it or write anything. I accepted her decision.)

This

allowing sources to hide behind a shield of anonymity was beginning to be a pattern. I've tried to avoid that approach the

rest of my career. I fully admit there are times when the gravity of the subject matter makes concessions necessary. I realize

some in academia would be critical of me for emphasizing that anonymity, even if highly qualified with explanations about

why sources weren't identified by name, should be a last resort.

As I neared graduation at CU,

I took a journalism class from Professor Sam Archibald, considered one of the godfathers of the Freedom of Information Act.

Here's his bio from when he was inducted into the inaugural class of the National Freedom of Information Hall of FameLinks to an external site. in 1996:

Samuel J. Archibald—As

chief of staff of the Government Information Subcommittee in the House, he helped draft the original FOIA legislation.

A former reporter with the Sacramento Bee, he was hired by California Rep. John Moss as an aide and became a key player in

Moss’ investigation of government secrecy, which led to the passage of the FOIA in 1966. He later became director

of the Washington office of the Freedom of Information Center.

When I took Sam's class, he chided me for fooling

around with the trivialities of sports and suggested I was capable of more "serious" work.

Even

after I got my CU diplomas and went to work full-time in The Denver Post sports department, I

kept Sam's prodding in mind. I tried not to let a PR man's tip become a "source" revelation, which still is the

disgusting trend in sports journalism. A favored-status tip from a PR person is not praiseworthy journalism, especially against

the current backdrop of the "scoop" often lasting roughly five minutes before an announcement.

Among

the stories I remember were ones as "minor" as relentless pursuits of who might get a coaching job; an exhausting

check around the National Hockey League to weigh the validity of the Colorado Rockies' claim that a horribly unfair arena

lease was going to drive them out of town; and the bona fides of a new prospective owner. For the latter, I took a call from

a man who never identified himself saying I should contact the Missouri Secretary of State's office and ask about the Rockies'

possible savior, and that would just get me a start. We ended up running a picture of one of the prospective owner's bounced

business checks. I visited him in St. Louis. He couldn't have been more cordial, but he soon withdrew from negotiating with

the Rockies' ownership.

Later, I was part of a two-writer tandem able to document the curious story of the

Denver Nuggets having an off-duty police officer shadow their star player, David Thompson, perhaps checking in to the possibility

of voiding his eye-popping $800,000-a-year contract. I was told that some NBA players routinely bought drugs at a restaurant

near McNichols Sports Arena, and that the primary dealer was a Denver fireman. The story was complicated and the Nuggets never

pursued came close to trying to void his deal. Thompson eventually was traded to Seattle and he long ago made peace

with the Nuggets management of the time.

At The Sporting News, I went to

Fayetteville, Arkansas to write about the suicide of Arkansas Razorbacks linebacker Shannon Wright. The story was heartbreaking

and I learned more than I felt I could write. (That's always part of the test, too.)

Those are a few of the

journalism stories I did, and it continued over the years. I also did exhaustive research for most of my books, and I proudly

count that as investigative journalism, too. So is in-depth interviewing, having the skill to ask perceptive questions and listen and respond to the answers. To me, the definition of "investigative"

can encompass far more than making document or other requests through sunshine and open-records laws.

As

we proceed through the semester, we'll try to look at as many approaches as possible.