April 21, 2021

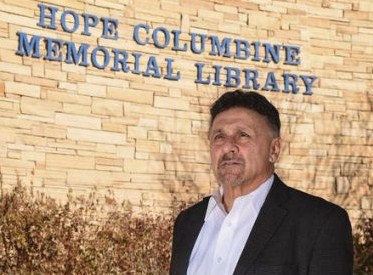

On the day after the 22-year benchmark since the horrific -- and unfortunately trend-setting

-- Columbine murders, the school's former principal and I hooked up for an updating chat.

After making numerous television appearances

throughout Tuesday, amid the coverage of the Derek Chauvin trial in Minneapolis, Frank DeAngelis was emotionally spent.

He also was regretful

that the deaths of the Columbine Thirteen on April 20, 1999 didn't serve as enough of a wakeup call to prevent school shootings

-- or mass shootings, period -- from happening again. And again. And again.

In the process of helping Frank with what turned

out to be his 2019 book, They Call Me "Mr. De": The story of Columbine's Heart, Resilience, and Recovery,

I was struck by the give-and-take involved in some of our discussions. (We first encountered each other as Ranum vs. Wheat

Ridge high-school baseball opponents, and one of these days Frank will believe that I, as a young catcher, didn't order Farmers

pitcher Dave Logan to plunk him. Even then, nobody ordered Dave to do anything.) Frank's point about gun control is that it's

a mistake to focus so tightly on that issue that other parts of "the puzzle" are overlooked or underplayed.

Most

notably, Frank's position on gun-control measures during our book discussions was less strident than mine. That's certainly

not because he's insensitive to the toll. There are few on the planet who are more sensitive to it, and I think that shows

in the book. But he's more pragmatic than I am, and far more capable of understanding the need for nuance in views to have

a chance to affect change, especially in an America increasingly prone to oversimplification, predictability and polarization.

If

you read the excerpt below, I believe you'll note his position on the issue is not a betrayal of the gun-control cause, but

based in realism about the need -- cliche alert -- for "common sense" gun laws as a starting point. It could help

prevent the carnage from leading to the it-happened-again reaction I've written about recently after mass shootings in Boulder and Indianapolis. Plus, I've again written about Columbine and guns.

So on Wednesday, I asked Frank

if his views on gun control had changed since They Call Me "Mr. De" was published -- and if he wished

he had been even more strident about the issue in the book.

Much of what we talked about is a repeat of his views in the chapter below. That's

high praise, actually.

"When I'm pushed in a corner is when people are saying the only thing we have to do is have

tougher gun laws and we'll never have any more violence," DeAngelis said. "I struggle with semi-automatic weapons.

I struggle with 30-round magazines. When people say they need it for self-defense or hunting ... you do not. At the same time,

I do hope that if we come up with tougher gun laws, we don't eliminate concern about some of the other things that are contributing

to some of the issues we're having right now. Guns are one piece of it."

He brought up mental health.

"I get worried

when I hear schools talking about cutting social workers or mental health workers or counselors," DeAngelis said. "One

of the things I'm working with right now is the teenage suicide rate has gone up. You worry about that, too. I even worry

about social media and what these kids are doing with social media. We're old people..."-- uh, speak for yourself, Frank

-- "...and I worry about these parents being aware of what's happening on social media? Are there warning signs that

would stop some of these things from happening?"

He also mentioned the Safe2Tell watchdog system in which students can anonymously report

threats or threatening behavior. I've written about that, too.

"I

think it's all these things that contribute," he said. "After Boulder, I was asked again and again, 'What's the

solution?' I wish I knew the one solution. What I do know is these senseless deaths need to stop and we need to find answers.

Guns is a major issue right now, but I think we have to look at these other things I've talked about."

From: They Call Me 'Mr De':

The Story of Columbine's Heart,

Resilience, and Recovery

(Used with permission)

By Frank DeAngelis, 2019

Chapter Twenty-One:

Gun

Rights . . . and Wrongs

Every public or mass

shooting inevitably restarts the debate over gun control. That was true with Columbine, and it was true after the horrific

events in Las Vegas on October 1, 2017, when a single shooter with an arsenal in his thirty-second floor room at the Mandalay

Bay Hotel fired down into a country music festival crowd, killing fifty-eight and wounding many more, and it became a heated

topic after the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shootings on February 14, 2018. The students at the school took their

concerns nationwide, calling for action with national leaders.

At Columbine, the killers had a TEC-DC 9 semi-automatic handgun, a 9mm carbine, a

sawed-off 12-gauge pump shotgun, and a sawed-off double-barreled shotgun. They did the sawing off themselves, making the

guns easier to conceal but more difficult to shoot accurately.

Neither Harris nor Klebold were eighteen in November 1998 when they attended the Tanner

Gun Show, which was held almost every month at the Denver Merchandise Mart in Adams County, just beyond the Denver city

limits. There they scouted out possible purchases, then returned the next day with Klebold’s friend and later his prom

date, Robyn Anderson, an excellent student and nice girl active in church organizations. She had just turned eighteen, which

made her old enough to purchase guns.

Dealers at the show were both federally licensed and unlicensed. Unlicensed meant relatively

unregulated, with less paperwork and scrutiny. All that I’ve read leads me to believe that it was obvious that Anderson

was buying for Harris and Klebold, who were with her. But with a driver’s license that showed she was eighteen, she

was the official and legal purchaser of the carbine and the two shotguns from three different private, unlicensed dealers.

Anderson paid cash—the killers’ cash—and she later said she didn’t have to fill out anything, and

there were no receipts involved. Under Colorado law, an eighteen-year-old without a felony record could legally furnish minors

with “long guns” (i.e., rifles and shotguns). Federal laws about “straw” shotgun and rifle sales—sales

in which others purchase guns for minors—and sales to minors were tighter, but only applied to licensed dealers.

After the killings,

a horrified Anderson told her mother about the gun purchases, and her mother took her to the school, where the Columbine

Task Force had set up in the band room. She was questioned for four hours, but was insistent she had no idea about the killers’

plans for the guns. Anderson later said that if she’d had to undergo a background check or fill out extensive paperwork,

she would have balked at making the purchases. She was never charged with a crime.

Tom Mauser, the father of the murdered

Daniel Mauser, took a one-year leave of absence from his job at the Colorado Department of Transportation to be a lobbyist

for an organization proposing more strict gun control laws in Colorado. When the legislature wasn’t very responsive,

and the few bills that did passed were weak, Mauser’s organization led the successful petition drive to get Amendment

22 on the November 2000 ballot. The initiative, billed as closing the gun-show loophole, passed decisively, requiring background

checks for buyers of firearms at gun shows. The state also required all transactions at the shows to go through licensed

dealers. Then in 2013, Colorado began requiring even unlicensed sellers to run background checks on buyers in all transactions,

not just at shows. The only exception was for antique guns.

If those laws had been in effect in 1998 and 1999, perhaps the killers would have

managed to acquire three “long guns,” anyway. But they would have had to go about it differently and might have

drawn attention to themselves.

The handgun, the TEC-DC 9, came from Mark Manes, introduced to Harris and Klebold by their fellow

Blackjack Pizza employee Philip Duran. Manes sold the killers the gun, which he had purchased at an earlier Tanner show,

for $500. On the Basement Tapes, the killers thanked Manes for helping them acquire the TEC-DC9, used by Klebold on April

20, 1999. The tapes also showed them talking about trying out the gun, shooting at a tree and chortling about what the gun

could do to a victim. Both Manes and Duran eventually were charged with selling a handgun—as opposed to a “long

gun”—to minors and served prison time.

To the disappointment of some, I am not a militant absolutist on gun control, primarily

because I believe banning all guns won’t get much done. I believe it is one piece to the puzzle. Other pieces are

mental health, background checks, the role that social media plays, parenting, plus law enforcement and judicial systems

working together with schools.

I have friends who strongly believe in the right to bear arms and who oppose significant gun

control legislation, saying the problem is with society, not with guns. I realize that people who intend to commit murder

will purchase weapons illegally, if necessary. Chicago has some of the toughest gun laws in the country and has the highest

homicide rate.

I know that supporters of tougher gun laws argue that the guns being used in Chicago are being purchased in states

where their laws are more lax and being brought into Chicago. I respect the gun rights advocates’ right to their opinion.

Law-abiding citizens do whatever they need to do to follow the laws.

How do you stop the excesses in a society where it’s made easy for guns to be

purchased illegally, and where it still isn’t hard enough to purchase guns legally?

That’s where I struggle. I believe

there should be some middle ground that helps lessen the chances of mass killings, and reasonable measures such as those

championed by Tom Mauser are praiseworthy steps in the right direction. I can’t reconcile the idea of an eighteen-year-old

girl buying guns that have no productive use in society. Ultimately, these guns were used for their intended purpose, to

kill and wound. Yes, there’s something wrong with laws that allow that to happen.

Loopholes still exist, and they need to

be closed. And it’s hard for me to imagine why anyone would need a thirty-round magazine for self-protection. (Answer:

Nobody does.)

I do believe that common sense needs to be used by both sides.

I don’t agree with the premise that everyone should own a gun, but it is an

individual right. A majority of gun owners are law-abiding citizens. I don’t believe teachers or administrators should

be armed or have access to guns. I wonder how many educators would choose the profession knowing there is the possibility

that they would be required to be armed.

That said, I do realize there are extenuating circumstances. During one panel I served

on, I shared my opinion about arming teachers. The panelist that followed me lived in a rural area, and he noted it would

take an inordinate amount of time for officers to respond there. He said they did have staff members who were armed, but

added they were former military or ex-police officers. I have had the good fortune to work with law enforcement officers,

and I have not found many who support arming teachers. A concern they have is that once anyone armed enters a building, adults

trying to protect the students usually can’t be certain they’ve got the potential shooters spotted. Plus, with

very few exceptions, staff members aren’t likely to fire with accuracy. I realize if laws ever are passed that would

allow teachers and administrators to carry guns, there would have to be stringent guidelines to allow school personnel to

carry.

School

resource officers are the better choice for enhancing school security. I’m a major supporter of armed school resource

officers, assigned from area police or sheriff forces. Mo Canady, the executive director of The National Association of

School Resource Officers (NASRO) argues that a well-founded school resource officer (SRO) program is one of the best possible

school security investments for any community. The return on that investment, however, goes well beyond school security.

(NASRO) strongly recommends that every school in America have at least one carefully selected, specially trained SRO as

opposed to arming teachers. Deputy Blaine Gaskill of the St. Mary’s County Sheriff ’s Office provides an example

of the impact an SRO can have. When a school shooting erupted at Great Mills High School in March 2018, Deputy Gaskill responded

directly to the threat and stopped the shooting. For this act of courage, Deputy Gaskill received NASRO’s 2018 National

Award of Valor.

NASRO recommends a triad approach to school policing in which every SRO serves the school community as (1) a mentor/

informal counselor, (2) an educator/guest lecturer, and (3) a law enforcement officer. The former two roles assist the latter

role. Developing positive relationships with students enables SROs to gather valuable information that helps them intervene

quickly.

I’ve talked to police officers about what might have happened if I’d had a gun on me that day, whether

that meant I always carried one or that I could get to one quickly in my office at the report of gunfire. When I ran out

of my office and saw Harris, who knows what I would have done if I’d spotted him sooner and he was closer? (Remember,

at that point, we didn’t know they had started their killing spree elsewhere. They could have been shooting up the

school, not committing murder.) I would have said, “Come on, there has to be a better way; put the gun down.”

I saw the gunman as one of my students. We can’t break down the possibilities second by second, but I believe that

if I had been carrying a gun and Harris had seen that, he might have reacted differently, whether before or after his initial

blast in my direction.

I also know that I could go out every week to a firing range and perfect my aim. But it’s the mental

piece that makes me question the wisdom of being armed: Would I be able to kill someone? Would I have hesitated to shoot?

Probably. And the officers I’ve spoken with agree that if I’d had a gun and didn’t fire it, Harris would

have killed me and the girls that day.

Police officers say that when they run into a building, they see the perpetrator.

They see a threat to others. They react. When an officer shoots, he or she isn’t aiming for the leg. He or she is doing

everything possible to stop the perpetrator(s) from killing innocent children.

Again, I am not against law-abiding citizens owning

guns. But I think we do need to look at both sides. Jaclyn Schildkraut, a professor at Oswego University, and H. Jaymi Elsass

did extensive research and wrote the book, Mass Shootings: Media, Myths, and Realities. Jaclyn later went on to

publish. Mass Shootings in America: Understanding the Debates, Causes, and Responses. The books present arguments

for the never-ending debate. It’s safe to say there aren’t guarantees that one thing can stop the mass shootings

from occurring.

Here’s another debate: Do violent video games or violence-themed music motivate potential mass killers? Good

question; I don’t have a definitive answer.

We must continue the fight to come up with plans and laws that have the potential

to stop the senseless murders. At my presentations, audience members often say something like, “Frank it is admirable

what you are doing, but school shootings continue.” My response is that they’re right, but I then ask how many

shooting plots have been foiled and how many lives have been saved because of lessons learned and things being done

differently after April 20, 1999.

Also:

This adapted excerpt from Patrick Ireland's project ran on ESPN.com in

2009