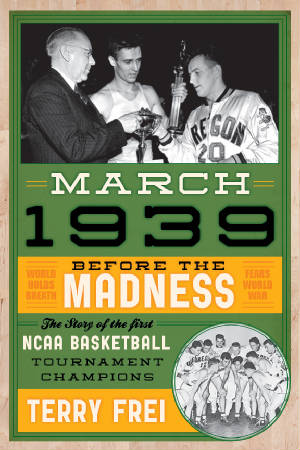

|

The Setup After routing Texas by 15 and Oklahoma by 18 in the West Regional, played

as part of the World's Fair on San Francisco's Treasure Island, the Webfoots climbed back on trains and made the three-day trip to Chicago for the March 27 national championship

game against Ohio State in Northwestern's Patten Gymnasium in Evanston. The championship game was to be played in conjunction with the National Association of Basketball Coaches convention

in Chicago. That was appropriate because the

first tournament was the NABC's baby, with nominal support from the NCAA itself. Long Island University had won the second national invitation tournament in New

York the previous week, beating New Mexico A&M,

Bradley and Loyola of Chicago. That six-team tournament,which also included St. John's and Roanoke College, was

run, promoted and shamelessly overhyped by the Metropolitan Basketball Writers' Association, which helps explain why myths about the early NIT -- with emphasis

on early -- are parroted to this

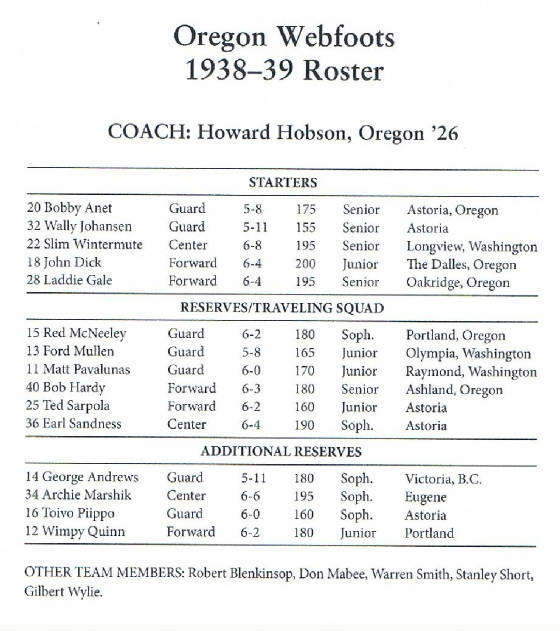

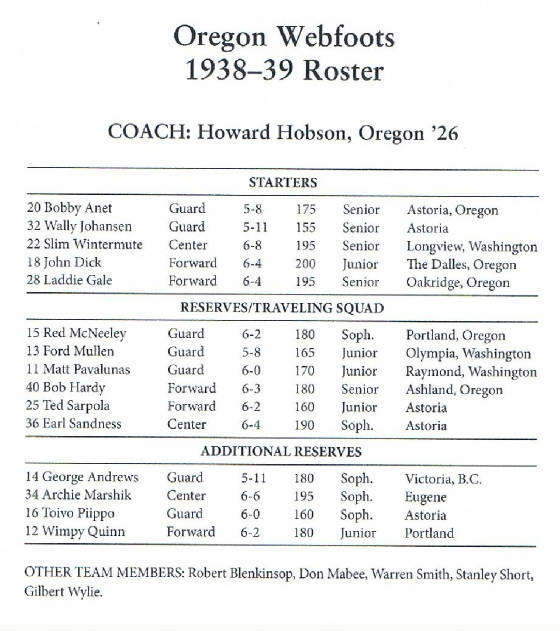

day.  The Webfoots' 14-man team at the opening practice. The traveling party for the NCAA tournament was

11 players. Including extra reserves and practice players, it's accurate to say that the Webfoots had a 20-man roster

that season, which has led to some confusion about who was on the famous championship team. See roster below.  The Webfoots' starters with coach Howard Hobson, right. Bobby Anet is seated.

Standing, from left: Slim Wintermute, Wally Johansen, John Dick, Laddie Gale. Game Night Monday, March 27 Regardless of when the coaches or fans arrived to Patten Gymnasium, they found that plenty of good

seats still were available.

Official attendance was 5,000 in the 9,000-seat arena on

the Northwestern campus, and many thought that was being charitable. [Future Denver Post editor and publisher] Charles Buxton of the Oregonian guessed 4,400—including the 400 coaches. Part of subsequent

myth would be that the tournament was little noticed in the nation’s newspapers and other press outlets. That’s partially

true. Leading up to the championship game, most papers ran only three- or four-paragraph wire stories about the Western and

Eastern championships and didn’t give them splashy play. The advance coverage and then stories about the national

championship game tended to get more space and better play. But it was relative: outside of New York, the national

invitation tournament got similar— or worse—play. On the national front,

boxing, horse racing, and baseball spring training were the big stories, and local papers supplemented that with

tales of the area sports teams. The NCAA tournament, while not given mega-coverage, wasn’t ignored, and the

stories about the championship game got more space. That said, though, there was no denying the fact that at least at

the box office, the NCAA tournament hadn’t caught on. So as the first NCAA championship

game began, the atmosphere was a mixed bag, with the nation’s coaches in the stands; with a stand-in chioldren's

band playing “Mighty Oregon” whenever it had the chance; with a radio broadcast; yet with many

empty seats. Most important, the Buckeyes and Webfoots stepped onto the mid-court circle for the opening jump ball

knowing they were playing for a national championship . . . and the right to be the first national champions. The championship and runner-up trophies were sitting at courtside, balanced on the scorer’s

table. The Buckeyes’ own coach was the head of the NCAA tournament committee and one of those most responsible

for the founding of the event in the first place. If he didn’t communicate that he believed this was the time

for true competitors to step up, he wasn’t a good coach. And he was a good coach. For

his part, Howard Hobson later reconstructed his pre-game discussion with [guard and captain] Bobby Anet. The coach was worried

that the train rides had left his boys tired.

“Bob,” Hobson said, “run ’em to

death if you can. Make them call the first time out. Make them say uncle first. Whatever you do, don’t call

time until you’re all in.”

Said Anet: “Okay, coach.”

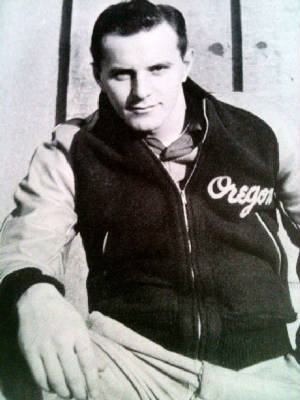

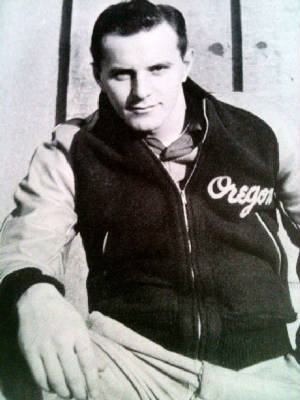

Bobby Anet Thirty seconds into the game, Anet ended up with the

ball after the carom of a Webfoots miss and tossed it into the hoop to open the scoring. On the next possession,

he was fouled and made a free throw, putting

the Webfoots up 3-0. Junior forward John Dick [later a Naval flyer in World War II/Korea, captain of the supercarrier USS

Saratoga during Vietnam and ultimately a rear admiral] added a free throw, and guard Wally Johansen’s

bucket made it 6-0. The Webfoots were on their way. Jimmy Hull finally

got the Buckeyes on the scoreboard with a free throw three and a half minutes into the game. The

Buckeyes seemed befuddled about how to attack the scrambling Ducks’ defense, couldn’t get the ball inside,

and settled for long—and bad—shots. And the coaches in the stands who hadn’t seen the Webfoots

before realized what they had heard was true, that they were both extraordinarily big along the front line but

also a mobile and speedy outfit, with the big men able to keep up with Anet and Johansen, the guards from Astoria.

That was what made this team both so good and so different. Although the Buckeyes

were playing in a Big Ten building, they ultimately appeared to be out of their league. At

the half, balanced Oregon was up 21-16. Johansen led the way with six points and Anet, [future Hall of Famer Laddie]

Gale, and Dick all had five. Slim Wintermute had yet to score, but was intimidating defensively and effective

on the boards.

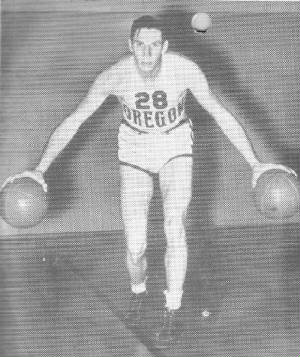

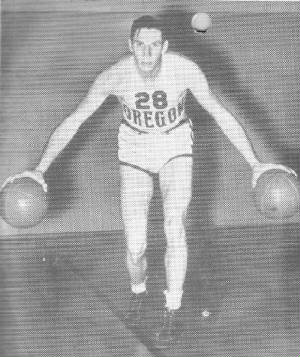

Laddie Gale Coach

Hobson later said that as the teams headed to the dressing rooms at halftime, he overheard Hull telling his teammates: “We’ll

run them into the ground in the second half.”

Johansen remarked to his coach, “I wish they’d

run a little but so we could work up a sweat. They play like they’re pooped.” The

Buckeyes indeed tried to pick up the pace and come from behind, and for a minute or two, it worked. Hull scored twice

after the break to cut the lead to 21-20. Then Wintermute hit two baskets (for his only four points of the game),

and Dick and Anet also scored in the run that put the Webfoots back up 29-20, still with over 17 minutes to play.

Again, the Webfoots’ defensive strategy fooled their opponents, as they went from a zone to man-to-man, but

Ohio State didn’t recognize it as such in time. From then on, the Webfoots never were in trouble. At one point, Anet charged after a loose ball and fell over the press row while attempting to save

the ball from going out of bounds. The little guard knocked over the championship trophy. “He

clipped off the figure of the basketball player that was on the top of the trophy,” Dick said. “He ended

up in the seats with the reporters.”

Later, his daughter, Peggy, asked him about the trophy.

“He said, ‘Well, I was just going for the ball and it was on the table there

and I knocked it over,’” she says. “I know he would have gone for the ball under any circumstances.”

When Anet came out of the game late, he got a standing ovation. Hobson later said his major

regret was that he got only two reserves—Matt Pavalunas and [future Phillies second baseman] Ford Mullen—in

the game and thus didn’t get all 11 boys memorialized in the box score of the first championship game. They were

far enough ahead that he could have pulled it off. Final score: Oregon 46, Ohio

State 33. Oregon never called a timeout. Ohio State called

five. After the game, Hobson asked Anet why he hadn’t at least called one with

the Webfoots holding a big lead in the second half. “You told me not to call one until we were tired,” Anet

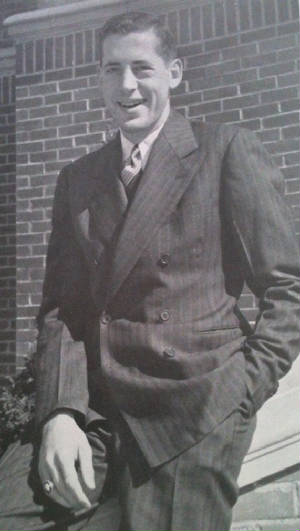

told his coach. “Hell, we’re not tired.” Dick, who led the

Webfoots with 13 points, never pretended that the game was well played. “Both teams shot poorly,” he

said. “I blamed our poor shooting on the lack of practice. We hadn’t had a real practice since the day before the

first Cal game [in the PCC championship series], twelve days earlier. I felt their poor shooting stemmed from their inability to

penetrate our team defense. In spite of our poor marksmanship, with our strong defense and control of the boards, we

slowly built our lead. Our big size advantage was a major factor in our success, as was the speed and quickness

of our guards, which they couldn’t match.”

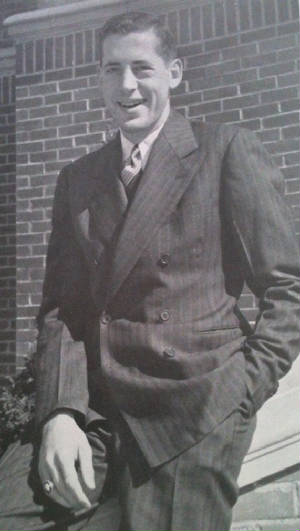

John Dick as the University of Oregon's student body president in 1939-40

The unofficial tally was that the Webfoots made 17 of their

63 shots from the floor, the Buckeyes 14 of 83. Anet and Gale both finished with ten points for the Webfoots, and

Johansen added nine. The Buckeyes in later years would assert their hearts weren’t in the game,

and Hull said his ankle still was troubling him. “My leg just felt terrible,” he said. “I had more

pain in it than you can imagine, and more tape on it than stores have on their shelves. And my accuracy just wasn’t

there.” Still, he led the Buckeyes with 12 points. And they were blown out by a team that hadn’t been

home in ten days, had spent much of that time on trains, and came to generally scoff at the Buckeyes’ alleged indifference

about the game as excuse-making, even if the Buckeyes came to believe it all themselves. Postgame Anet, wearing his warm-up jacket with the duck on the shoulder, accepted

the broken championship trophy in two pieces. Hull, next to him, held the runner-up trophy. Nobody rushed the court, not

even the Oregon alumni in attendance. The celebration was more about handshakes and pats on the back than exultation.

The Webfoots were thrilled and gratified, but they didn’t realize what this would mean. They

were the first champions.

"In the final 12 days of our season, we had won five

games, four of them in one six-day period,” Dick said. “We had won the championship final game against

the well-rested Big Ten champion playing close to home on a Big Ten court, with Big Ten referees and an overwhelmingly

Big Ten crowd.” Anet again was interviewed on the makeshift radio broadcast after

the game. Anet gave credit to his teammates, and the radio man pressed him: What about you? You played pretty well,

too! Anet laughed, shrugged, and said something along the lines of: Huh? He

was cocky and self-assured on the court and usually away from it, too, but at least this time, the microphone turned

him into a cliché-spouting milquetoast. Since reporters rarely interviewed and quoted players, mainly because

the print scribes believed their job was to provide the facts, opinion, and perhaps a narrative in the era before games

were televised, Anet didn’t have much practice at speaking for the record or on the air. None

of the Webfoots did, as a matter of fact.

Asked later to assess the game, Laddie Gale said: “Ohio

State was really a setup for our kind of basketball. It used a fast break, which was right down our alley. Then

Ohio State had never seen our kind of zone defense, I don’t think, because the Big Ten team took 40 long

shots of its entire total. It couldn’t break through. Our height helped a lot because we could dominate the backboard.”

In the dressing room, with photographers jammed

in, too, the Webfoots made no moves to undress and shower. With Astoria pal Wally Johansen next to him, Anet leaned

against a hall in one corner and held the trophy—the broken championship trophy—as if he never was going

to let it out of his sight. Gale held a basketball against his rib cage, grinning as he watched Anet. * * *

In their quick dispatches from Evanston, the two major wire

services phrased it carefully.

The Associated Press dispatch began: “The University

of Oregon, displaying superior ball handling and shooting ability, defeated Ohio State tonight, 46 to 33, on the

Northwestern Court in the final for the basketball championship of the National Collegiate Athletic Association.”

The United Press dispatch at least acknowledged the elephant in the room—or on the

floor. It opened with: “Oregon’s rangy sharpshooters, new champions of the National Collegiate Athletic

association, entered a claim to the national intercollegiate

basketball title today, and it’s as good a claim as any other.” It gave the final score and said the

result “left no doubt of their superiority. . . . The national championship, however, still is a muddle. Long Island

University, victor in Manhattan’s invitational tournament, is a popular eastern choice for the title and Southwestern

Teachers of Winfield, Kan., won a similar tournament at Kansas City.”

'The mention of the small-schools Kansas

City tournament, while perhaps polite, was ridiculous. And LIU's undefeated record was made possible by a joke of

a schedule that included one -- one -- true road game. The Blackbirds were 15-0 at home in the 800-seat Brooklyn College

of Pharmacy gym against such powerhouses as Princeton Seminary, Panzer College, Stroudsberg Teachers and the John Marshall College

of Law; and, yes, 8-0 in games against just-got-off-the-train teams in Madison Square Garden's popular college

doubleheaders. Their only road game was at LaSalle.

On the way to finishing with a 29-5 record for the season,

Oregon won its three NCAA tournament games by 15 over Texas, 18 over Oklahoma, and 13 over Ohio State. In an era when

getting into the 50s was considered high scoring, those were astounding margins. At least among the teams that had earned and

accepted bids to the NCAA tournamentKentucky, Colorado and Missouri were amng those that turned down bids, including to the

play-ins in advance of the eight-team bracket), the Webfoots were by far the best. By the end of the season, they were

playing great basketball, hardened by their early-season marathon trip to the East Coast and back. They had much

tougher times with their PCC rivals, Washington and California, and they were convinced that even in the year after

the great Hank Luisetti finished his career at Stanford, the best basketball in the country was being played on the

West Coast. The fact of the matter, too, was that while Ohio State deserved much credit for its late-season rally to

the Big Ten title, it took an Indiana collapse for the Buckeyes to pull that off. While some of the Buckeyes’ downplaying of the significance of the NCAA

tournament later was retroactive and seemed a bit lame, it’s undoubtedly true that the Webfoots were happier to

be in Evanston. But, as Dick noted, even at the end of another grueling trip, the Webfoots routed

the Buckeyes. Many of the coaches watching imagined what a game between the LIU Blackbirds and

the Webfoots would be like. It would be wrong, though, to portray this as a debate raging at lunch counters from

coast to coast over the next few weeks. Even among sports fans, it came down to the fact that LIU and Oregon each had

won a tournament with “national” in its name and that Oregon’s tournament involved teams from

all parts of the country.

[Madison Square Garden promoter] Ned Irish was at the NCAA

title game, too, and he broke the ice with Coach Hobson by congratulating him and lamenting that, wow, if Hobson

thought the East Coast officiating was bad, what about these guys? Hadn’t the Webfoots had to overcome the Big

Ten refs, too? Irish already had an LIU-Oregon game in mind for the Garden the next season. With

only John Dick returning from among the Webfoots starters, and with LIU set to be similarly depleted, such a matchup

wouldn’t provide a retroactive answer about which team was better in 1938–39, but Irish was thinking box

office. "These kids

nowadays..." In Eugene, after

the game and the radio broadcast ended a little after 8 p.m., Oregon students spilled out into the streets, and the Register-Guard

the next morning would say they “took the town like Hitler took Czechoslovakia.” [Germany's forces invaded

Czechoslovakia 12 days before the game.] The students mostly went up and down Willamette Street, going in and out of

establishments and theaters, loudly celebrating the victory and saluting the Webfoots. The

Yell Kings led a spontaneous rally on the stage at the Heilig Theater, where Love Affair with Irene Dunn

and Charles Boyer was playing, and also burst into the McDonald Theater before the doorman at the nearby Mayflower,

where the feature was I’m From the City, got wind of what was going on and locked that theater’s

doors as the movie played. Eugene police turned off the traffic signals and allowed

Willamette Street to become a pedestrian mall with the cars stuck. Jennie Hobson, Howard’s wife, even

joined in. The celebration was spontaneous and raucous, and it seemed to be likely that many students would

skip their morning classes on Tuesday, although it would be only the second day back after spring break.

University President Donald Erb, who had been in office barely a year, still was only in

his late 30s, and was Hobson’s neighbor and friend, had made it clear that he wouldn’t cancel classes and that

Friday would be the official day of celebration, after the team returned. But the students partied as if they had nothing

against doing it twice. On 11th Street, fraternities brought out radios and staged

impromptu dances. Students pulled a dead tree that had been chopped down, but not hauled away, into the street to block it,

creating a safer and bigger dance floor. The large group of male students greeted police officers trying to keep an eye

on things by hoisting them on their shoulders, which the officers handled with good humor and aplomb, and then dropped

them and suggested they dance with the co-eds to “Flat Foot Floogie with a Floy Floy.” By

10:30, the tree was dragged off the street, the dance broke up, and the men continued on down the streets to the sororities,

where they stood outside and sung for the girls. The only real over-the-top behavior was the tossing of eggs near

the end of the celebration.

President Erb sent a telegram to Hobson, saying: “Congratulations to

you and the boys from 3,000 university students, a million Oregonians and me.” A Toast From the expense money kitty, each player was allotted about $2, and Anet and several of his teammates took a late commuter train into downtown Chicago and did some mild celebrating. “I

think some of us had a couple of Heinekens or

something,” Anet said later. “It

was quite late and none of us were big on bars or things like that, mainly because nobody ever had any money.” They toasted their

championship. The very first one.

Previous Excerpt: Meet the Starters

|