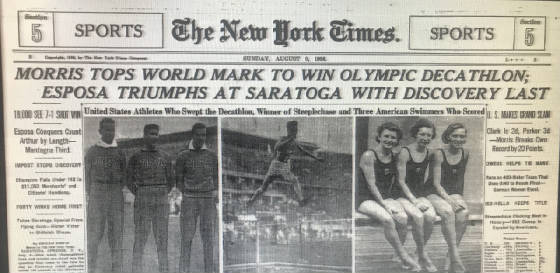

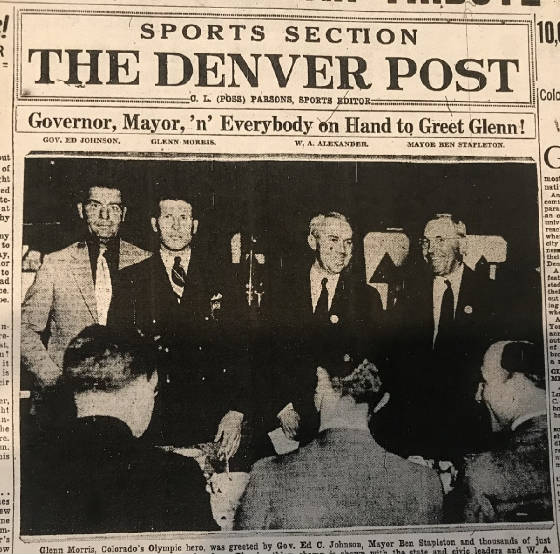

From this above in The Denver Post, August 9, 1936 ...

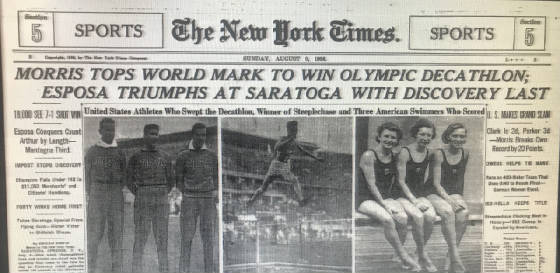

... and this in the New York Times

...

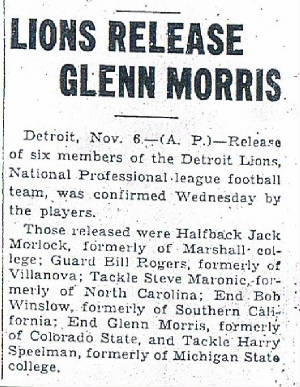

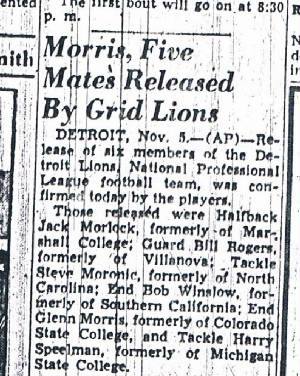

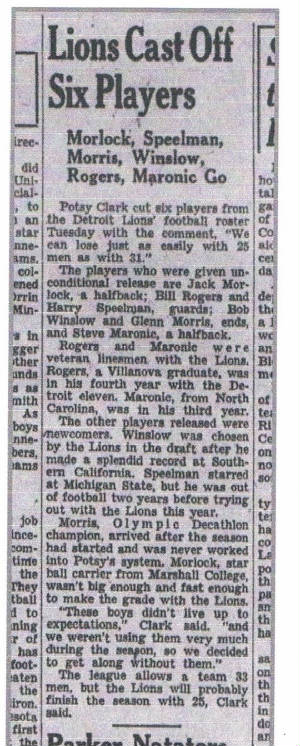

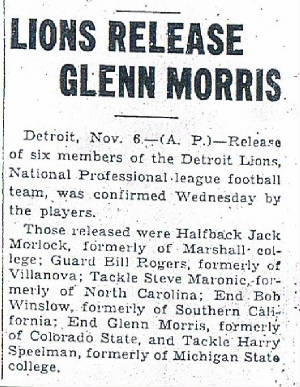

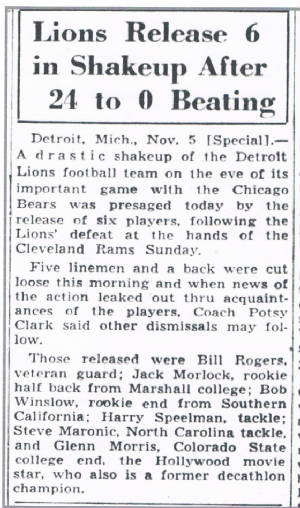

... to these duplicate and minimalist AP stories in Glenn

Morris' home-state papers, November 6, 1940. That's all. Morris is referred to only as being from Colorado State College.

That's it. In the Denver papers!

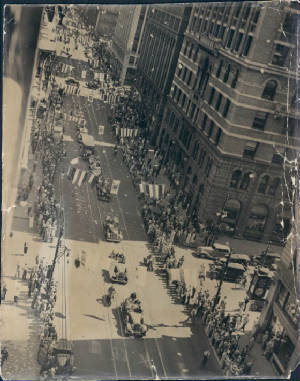

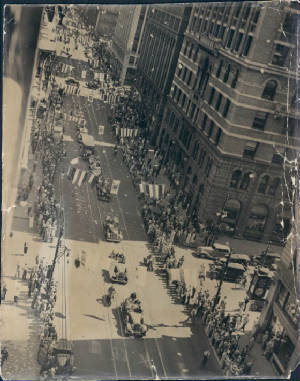

Top: Glenn Morris waving during the Olympians'

ticker-tape parade in Manhattan.

Right: New York

City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia greeting and congratulating Morris.

We're approaching the 80th anniversary of one of

the most curious player cuts in NFL history. It was curious because only four years earlier, Coloradan Glenn Morris had been

one of the most famous athletes in the word ... yet his release drew little attention.

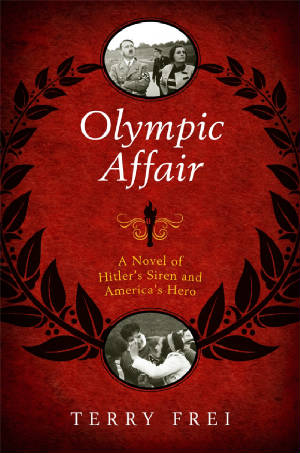

When writing Olympic Affair: Hitler's Siren and America's Hero, I ended the narrative before Morris -- the 1936 Olympic decathlon champion -- played for the

Detroit Lions. I mentioned it in an Epilogue

that told what happened from there to Morris and Leni Riefenstahl ("Hitler's Siren"), pictured together at right

during the decathlon.

Also,

an Author's Afterword explained my methodology in researching and then telling the story as a novel.

I viewed it as speculative fiction, scrupulously basing

it on what I knew to be true as much as possible, letting it play out on a screen in my head and filling in the blanks with

my imagination. And when I was done, I was gratified that what was billed as a novel was as much or more factual than many

other books labeled and shelved as "History." It and my other novel, The Witch's Season, are my best books ... though sales figures don't reflect

that. (Funny how that works.)

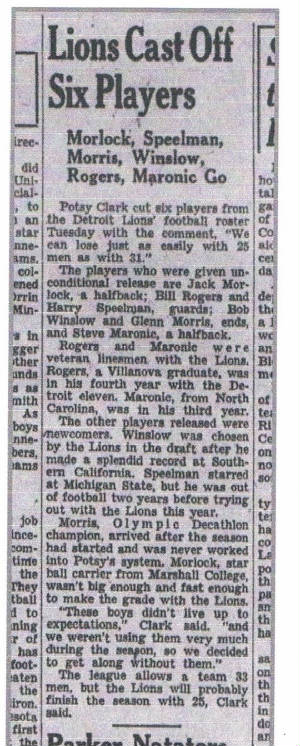

The Lions released Morris and five others on November 5, 1940. Three games remained in the regular season.

His release was barely noticed -- not just in Detroit, but also in Denver ... or nationally. One excuse: It was

Election Day, and Franklin Roosevelt defeated Wendell Willkie to earn a third term in the White House.

Morris was from tiny Simla, roughly halfway between Limon

and Colorado Springs southeast of Denver. He not only was a football (pictured at right as an Aggie) star at CSU, but also

the student body president.

Then

in only the third decathlon of his life, he won the gold medal at the controversial Summer Games at Berlin.

With the despicable

Adolf Hitler noticeably cheering on the American from his private box, Morris finished with 7,900 points and broke his own

world record in a time when the Olympic decathlon winner was advanced as "the world's greatest athlete."

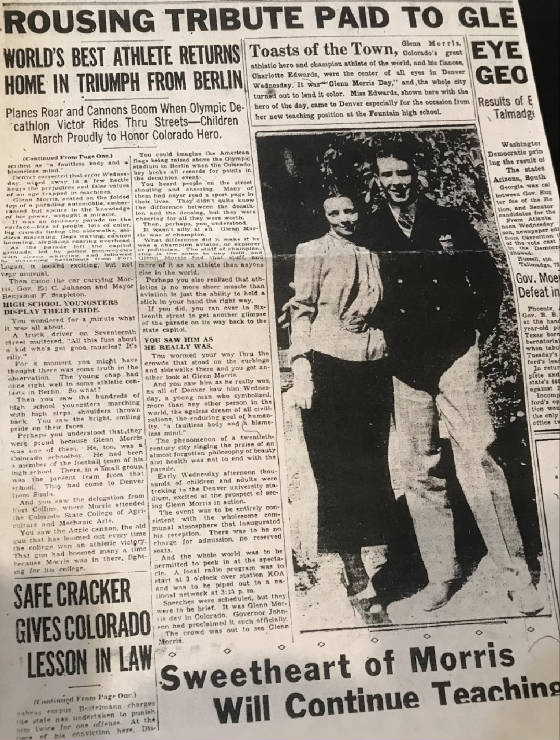

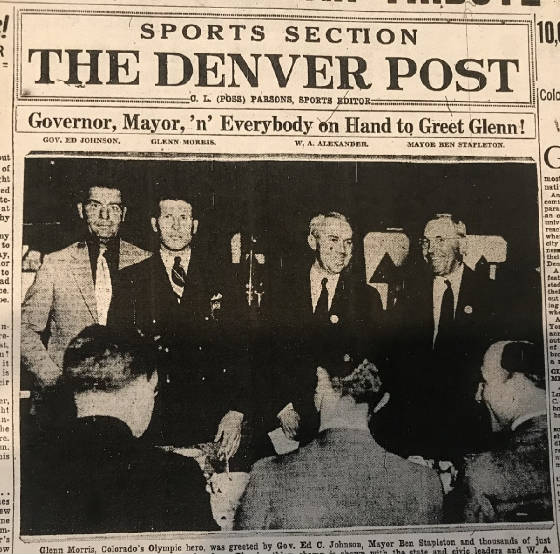

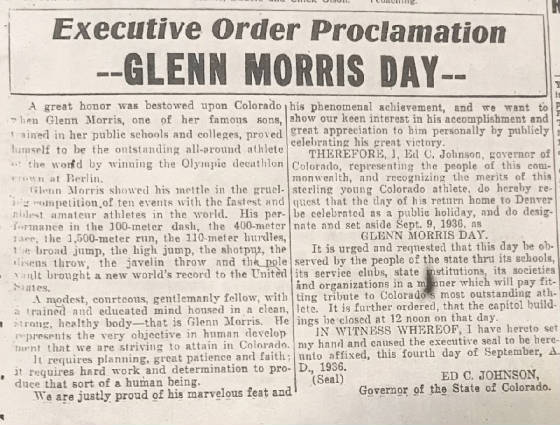

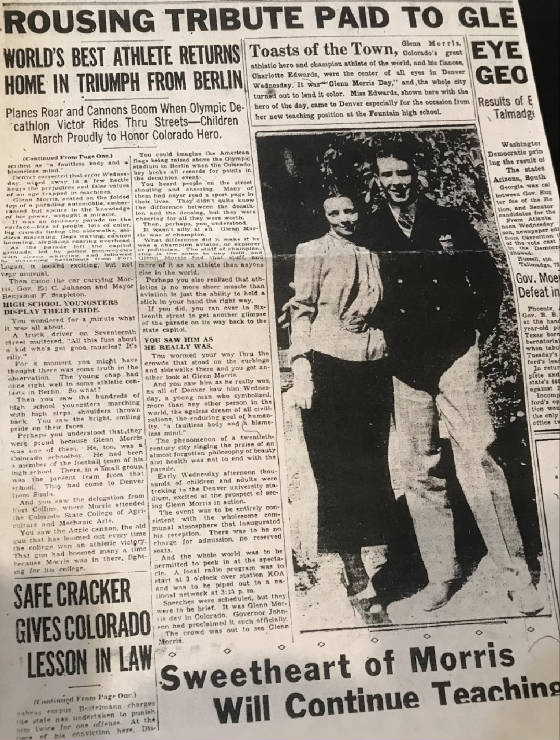

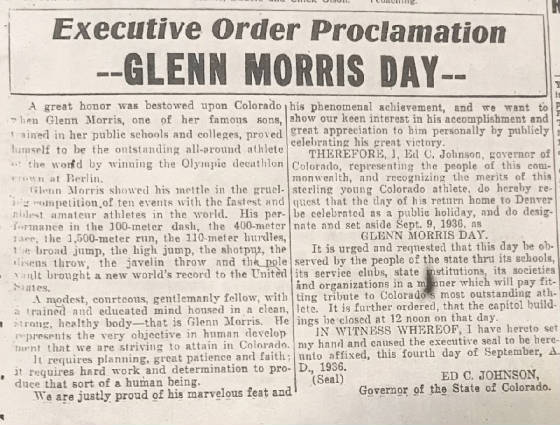

September 8, 1936: On "Glenn Morris

Day," he is feted with a downtown Denver

parade, left, and shows off his gold medal for the press.

Denver and Colorado politicians get into the act.

After the track and field

athletes returned from a competitive tour of Europe, Morris was one of the most prominent figures in a welcome-home parade

in Manhattan and then was solely feted in another parade through downtown Denver on "Glenn Morris Day." (As a post-collegiate

track competitor, he represented and was sponsored by the Denver Athletic Club.) He was a banner-headline figure not just

in the Denver papers, but around the world.

This didn't come out until later, but he also had an affair with Riefenstahl,

the manipulative actress-filmmaker. She had made the chilling and ultimately foreshadowing documentary, "Triumph

of the Will," about the Nazi Party Congress at Nuremberg. At the Games and shortly after in restagings, she was making

what ultimately would be "Olympia," the acclaimed documentary about the Games. She claimed to be an independent

artist doing a job while not deeply aligned with the Nazi Party and Hitler. That, of course, was absurd.

Disclosing the affair

years later in her autobiography, she said Morris -- who soon after returning to the U.S. married his college girlfriend --

had dumped her and she was both bitter and brokenhearted, a stunning admission for a manipulative woman who tended to get

whatever she wanted.

Morris won the Sullivan Award as the nation's top amateur athlete in 1936, in part because four-time gold medalist

Jesse Owens had angered AAU officials by immediately turning pro for running exhibitions and appearances after the Games.

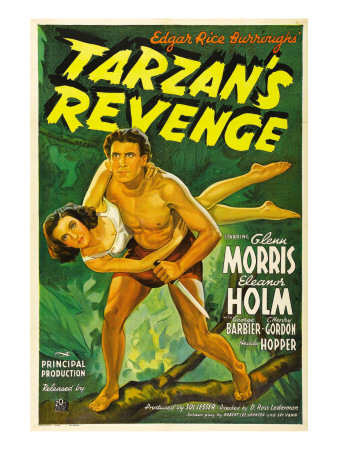

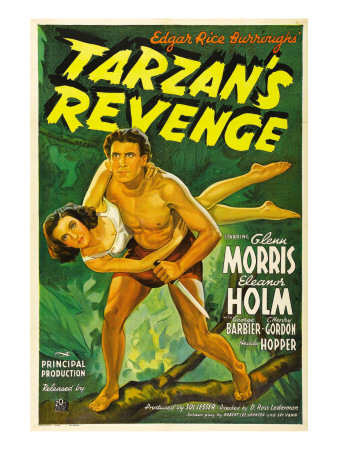

He played Tarzan in the dreadful 1938 film "Tarzan's

Revenge," co-starring with former Olympic swimmer Eleanor Holm. They hated each other, so their best acting was pretending

to have a screen chemistry. After the film came out, and as he was living in the Los Angeles area, he was accused of spousal

abuse and soon divorced.

Not getting any career traction, he joined the Lions early in the 1940 season. There are no indications

the Lions did it as a publicity stunt. His fame had been fleeting -- my theory was that Riefenstahl was toxic -- and he was

just a guy by then, trying the NFL at a time when accepting pro offers wasn't automatic. Guys actually went into family insurance

businesses if the contract wasn't good enough.

Another small-town Colorado product -- former three-sport CU star Byron "Whizzer"

White, from Wellington -- was the Lions' star as he moved toward a carer in law. (How'd that work out?)

With the Lions, Morris didn't catch a pass.

He had one interception. He tackled the Chicago Cardinals' Milt Popovich for a safety in a 43-14 Lions win on Oct. 5. That

was it, and he was cut a month after joining the Lions. To put it in perspective, other Olympic track and field athletes have

tried the NFL since with mixed results, but Morris was a bona fide football star at CSU who had just taken up the decathlon.

Curiously, his release merited only a passing mention in a Detroit Free Press story

noting that the 3-4-1 Lions cut six players as a stretch-run cost-cutting move. That's the way it was done in those days of

varying and fluctuating roster sizes.. If you were out of it, you cleared salaries, even given the scant payrolls of the time.

Even more bizarre,

though, was the lack of notice the Lions' move received in Denver.

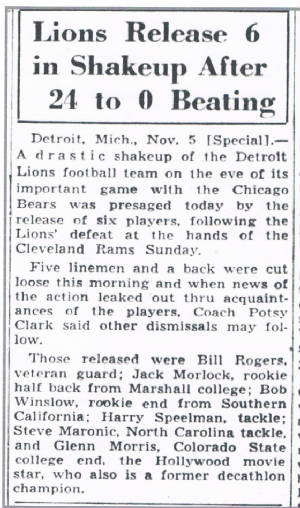

This from the November

6 Free Press. This at least had a hint of Morris' previous prominence, but also had a gratuitous shot from coach

Potsy Clark.

It seems that

a grizzled copy editor at the Chicago Tribune made the connection, touching up the AP story and labeling

it "Special," which was the way it was done at the time. So the Trib at least identified

him a bit more extensively in this story:

Morris briefly joined the Columbus Bullies of the American Football League

-- not the AFL that eventually would merge with the NFL -- late in the season. Soon, he was back in Denver, selling

insurance.

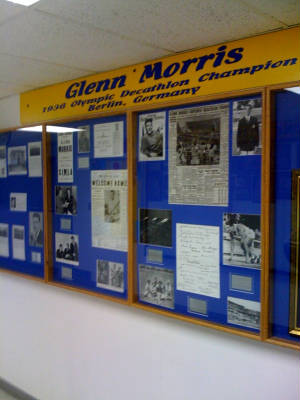

He served in the Navy and was a beachmaster in the Pacific landings during

World War II, then lived in Northern California and was a troubled and unhealthy steel rigger. Along with former Lions teammate

Whizzer White, Morris was inducted in the Colorado Sports Hall of Fame's inaugural class in 1969, but sent regrets and said

he was too ill to attend. When he died in 1974, he was 61 and mostly living in a veteran's hospital.

Also on this site: