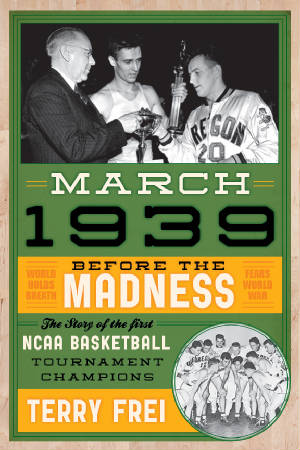

| |

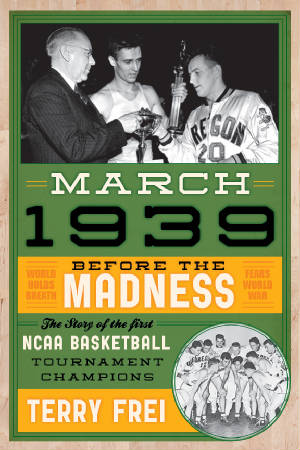

The Ducks' starters with coach Howard Hobson, at right. Guard Bobby Anet is seated. Around him, from left: Slim Wintermute, Wally Johansen, John Dick, Laddie

Gale.

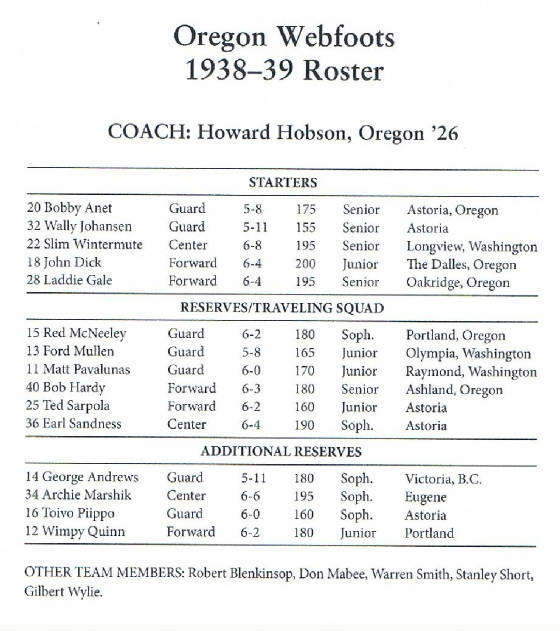

NOTE: [Bracketed material] below has been added here for context and background

purposes, but is covered elsewhere in the book. Fishermen

Bobby Anet and Wally Johansen lived across the street from each other in Astoria, on the south shore of the Columbia River and only six miles from where it flows into the Pacific Ocean at the extreme northwest tip of Oregon. Both born in August 1917 and only 15 days apart in age, the boys were inseparable ever since . . . well, since at least as far back as they could remember.

Despite its well-deserved image as a haven for Finnish immigrants, many of them gill-net fishermen, Astoria’s populace was diverse. Heck, there weren’t only Finns; there also

were many Swedes and Norwegians. And, as years went on,

Chinese and Japanese immigrants also joined the labor

force.

Anet and Johansen were raised in Astoria’s Uniontown, or what also was called “Finntown” or “Little Helsinki.” Although their Lincoln Street was too hilly for a hoop, they knew the other hotspots in town, and if local drivers came across a street basketball game in progress, they stopped for a suitable break in the action and a wave-through before they proceeded.

Everybody knew the local

protocols in Astoria—and, for the most part, followed

them.

Founded in 1811 as Fort Astor by John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company, the town’s character and economic lifeblood were reflected in Astoria High’s athletic team nickname: Fishermen. In the late 19th century, the area was the world’s largest source of salmon, but the aggressive harvesting took its toll and by the 1920s, the fishing industry, while still viable, had slowed. A devastating 1922 fire destroyed 32 blocks, roughly one-quarter of the downtown, and about 200 businesses, including a logging mill. Wooden plank streets fueled the fire, and the rebuilding efforts and strategies recognized that it was imperative to replace all streets with pavement, an expensive proposition. For a brief time, the Ku Klux Klan gained a foothold in Astoria, but its influence waned and a Klan burning of a 35-foot cross on the area’s Coxcomb Hill in 1925 was considered a last hurrah.

Bobby Anet’s grandfather

and grandmother came to the United States in the late

1870s, shortening the family name from its original Anetjärve

(“people by the lake”) and settling in Astoria after abrief residency in Michigan. After a failed 1896 fishermen’s strike against the canneries and their fish trapping methods, about 200 of the Finns formed their own Union Fishermen’s Cooperative Packing Company, and it flourished, becoming the biggest in Astoria. Bobby’s father, Charles Anet, became the secretary-treasurer of the cooperative and also was involved in other businesses, including the area lumber mills. He married Hilda Urell, a Swedish-Finnish woman seven years his junior, and they had four children, two boys and two girls. The family’s four-bedroom home reflected an upper-middle class status, even in the Depression years. One of the family pastimes was to look out from the house on the hill, down to the Columbia River, and watch the ferry run between the Oregon and Washington

sides. At one point, Bobby and his younger brother, Cliff,

and their friends constructed homemade sailboats out of salmon

boxes and tried to race the ferry across the river. If Bobby’s ramshackle boat had capsized, someone else might have been the Oregon Webfoots’ captain in 1938–39. Some folks on the ferry grinned at the boys’ nerve, but the crew was not amused. Hilda Anet got a phone call from the captain. “Get those kids off the river right now!” he roared.

From then on, Hilda was even more encouraging of Bobby’s passion for sports.

Across the street, Wally Johansen’s father, Arthur, was a fireman and his mother, Anna, was a housewife.

In the wake of the huge fire, Anet

and Johansen and all the Astoria boys of their generation

were excited when the new Liberty Theater opened in 1925

as part of the rebuilding of downtown. In the tradition

of the times, silent movies were shown around Vaudeville-type

acts. The next year, schoolchildren reveled in a three-day

Astoria celebration to commemorate the opening of the Astoria

Column, a 125-foot high monument decorated with 14 paintings

of Astoria historical significance. The Column became a

mandatory stop for visitors and tourists and a source of pride for local residents.

Anet and Johansen went though the town’s youth basketball program together, winning a state age-group title playing for young YMCA physical director and coach Dick Strite, who took great pride in the progress of his young charges. Born in Maryland and raised in New York, Strite was a star athlete at the YMCA-run McBurney Prep School in New York

and a lifeguard on Long Beach in the summers. He then

attended the YMCA-run school in Springfield where James Naismith, then a YMCA physical director himself, invented the game. (At the time, it was called the International YMCA College.) After returning to New York, he got his YMCA career started in Brooklyn. Soon, though, he succumbed to the urge to head west to join his brother, Dan, and they worked together in the lumber trade in the forests near Garibaldi, in Oregon’s Tillamook Bay area. Calling on

his YMCA experience and connections,Strite soon landed the

physical director job at the Astoria Yand got out of the forests.

Astoria’s population dipped from around 14,000 in 1920, to about 10,000 in 1930, and basketball could be a distraction. As Anet and Johansen reached Astoria High, their coach was the beloved “Honest John” Warren, a native of eastern Oregon who got into coaching at Astoria following his football career at the U of O and his 1928 graduation. Realizing he knew far more about football than basketball, he attended summer basketball coaching camps in the early years of his Astoria tenure. A quick learner, he guided the Fishermen to four state high school basketball championships in six seasons—in 1930, ’32, ’34, and ’35. In writing about Warren’s early teams, the Oregonian’s L. H.

Gregory, who became sports editor at the state’s

largest newspaper in 1921 and never felt as if writing

about high school sports and athletes was beneath him,

labeled them the “Flying Finns,” but was corrected and told there was only one Finn on the team. By the time the1934 and ’35 teams also won state titles, though, the nickname fit. The boys from Lincoln Street, plus several other Finnish boys were instrumental in winning those final two titles. The Fishermen were 39-4 and beat Klamath Union in the 1934 championship game, then repeated in ’35, going 40-4 and knocking off Portland’s Jefferson High

to win the title.

By the time they were leaving high school, Anet and Johansen had been working in the fishing industry for several years. That was typical in Astoria for the teenaged boys, even in a time when the U.S. economic malaise considerably

weakened the industry. While working for the cooperative

in his teenage years, Bobby Anet was captain of several

gill-net boats and cannery tenders, the boats that transported

the fish to the cannery so the fishermen could stay out on

the water. He was out both on the Columbia River and on the Pacific Ocean. Johansen’s experience likely was

similar, in part because the two boys seemed to do everything

together.

Between Anet and Johansen’s high school championship seasons, Chancellor Adolf Hitler assumed complete and undisputed power in Germany following the death of President Paul von Hindenburg in August 1934. With so many immigrants from Europe in Astoria, the situation was the topic of discussion in the bars and on the docks. That is, they talked about it when they weren’t talking about those boys who were making the town the high school basketball capital of Oregon—including those two guards who played so well together.

Astoria, Oregon Using the designations that appeared in lineups, programs, and box scores, Anet was the “lg” (left guard), Johansen the “rg”

(right guard). At Astoria and almost everywhere else,

offensive diagrams and plays were drawn up with both guards

roughly parallel on each side, and either could handle

the ball and start the play. As the energizer and leader,

Anet ran the show for the Fishermen, and he didn’t

need to score to be effective: his highest-scoring game in high

school was only eight points. Johansen was the quiet, steady, and reliable complement in the backcourt, both in Astoria and later in Eugene. He could keep up with Anet, and he was a steady, two-handed outside shooter with a perfect follow-through that coaches used as an ideal for others.

Bobby and Wally didn’t have to look for each

other on the floor. They knew where the other was. They

headed off to the U of O together. The catch, though,

was that Anet went to Eugene on a football scholarship

as a quarterback, and while he intended to play two sports,

the “second” sport was baseball.

That plan would change. Other

Fishermen followed Anet and Johansen to Eugene. The first,

Ted Sarpola, was a year behind Anet and Johansen and led the

Fishermen in scoring for three consecutive seasons. In an era of haphazardly kept records, he generally was considered the first Oregon high school player to score 1,000 points in a career. Another year behind him, the lanky Earl Sandness took advantage of his deft inside moves and broke Sarpola’s record for most points in the four-game 1937 state tournament, scoring 68. A fifth ex-Astoria player, Toivo Piippo, also was on what Coach Hobson later listed as his full 20-man Oregon basketball roster for the 1938–39 season.

The Astoria pipeline didn’t involve only players, but also a coach and a sports writer.

As Hobson was about to be hired at Oregon in the spring of 1935, after Anet and Johansen’s senior high school seasons, he got fully behind “Honest John” Warren as the choice for the coach of the Oregon freshman teams, including in the basketball program. Warren’s

hiring, in fact, was announced at the same time as Hobson’s. Any Fishermen who chose the U of O would be playing for their former high school coach in their first year in Eugene. All of that was stunningly similar to a plotline of [former Long Island University basketball coach] Clair Bee’s Chip Hilton books. When Chip and a handful of his Valley Falls High School teammates left their small town and all went to State University, so did their high school coach, the beloved and sage Hank Rockwell. Bee’s book about Chip’s senior high school baseball season, Pitchers’ Duel, ends with the guest speaker

at the Valley Falls baseball banquet, State’s athletic

director, announcing the hiring of Rockwell as the university’s

new freshman coach in football, basketball, and baseball.

Chip and his pals, of course, are ecstatic that “The

Rock” will be joining them at college.

Bee

knew and coached against Hobson many times in the years leading

up to the period when he began writing the Hilton books in

the late 1940s [less than a decade after undefeated LIU, with the benefit of a stunningly soft schedule that included many

soft touches and only one true road game, won the second

national invitation tournament in 1939, a six-team event

run and ridicuously overhyped by the New York Basketball

Writers.] Bee undoubtedly noticed how the Webfoots’ coach assembled a significant portion of his glory-years roster from one small town. In fact, New York scribes jumped on the Astoria angle when writing about the Oregon team, and Bee couldn’t have missed that, either. Bee knew that Oregon also had brought in the town’s beloved coach to head up the freshmen programs. Bee acknowledged he drew on his background and experiences in writing the Hilton books, including when he used Seton Hall star Bob Davies as the model for Chip. He made Valley Falls High School’s teams the Big Reds; he could have called them the Fishermen.

And what of Anet and Johansen’s YMCA coach? Dick Strite left Astoria before his youth team stars reached high school, transferring to become physical director at the YMCA in Spokane, Washington.

Next, he moved to the Eugene Y, and apparently after dabbling

in sports writing on the side, he ended up the sports

editor of the Eugene Morning News in 1933, and then took over

the same job with the afternoon Eugene Register-Guard

in 1937. The YMCA man became a newspaperman. In his travels, he played basketball on various town and amateur teams. He also served as a referee for a while, until he groused that anyone who paid a fee and passed a lightweight rules test could officiate and that the standards were too low, so he didn’t want to be part of it any longer. By the 1938–39 season, he was in his mid-30s, married with two children, and with the two-finger typing eccentricities and habits common to the business.

A Eugene native who briefly worked for Strite after graduating from high school right after the end of World War II was Paul Simon, the son of the pastor at Eugene’s Grace Lutheran Church. Much later, Simon [by then a former publisher, U.S. Senator and presidential candidate] recalled: “Dick Strite wrote good stories, and expected the same of me. He also had the affliction of most journalists in that day, a love of whiskey and smoking. His top right-hand drawer had a fifth of whiskey in it, which he made clear I should not touch.” That was a decade after the Tall Firs passed through Eugene, but

it’s reasonable to assume Strite hadn’t just taken up smoking and drinking at the time. Yet it’s also perilous to apply modern standards to that, considering a bottle in a desk drawer wasn’t much of a rebel act in those times, and it could involve a toast of relief when another edition was put to bed. In addition to newspaper traditions, in which alcohol seemed as much a part of the business as typewriters and carbon paper, think of Ed Asner, as news director Lou Grant, occasionally pulling a bottle out of the drawer on the Mary Tyler

Moore Show in the 1970s. It didn’t seem irresponsible at all, did it? It was the way it was in newsrooms.

During the late 1930s, Strite occasionally mentioned his connection to Anet and Johansen in print, but didn’t overdo it.

So Warren, Anet, and Johansen—and, in a way, Strite [who became a prominent part of this story] — turned out to be a package deal, with other ex-Fishermen following them in subsequent years.

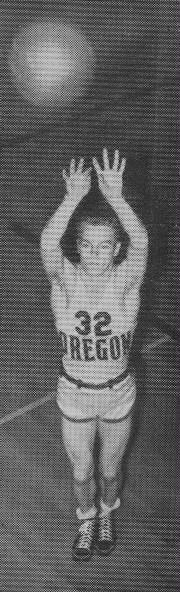

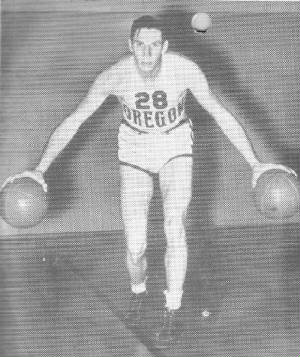

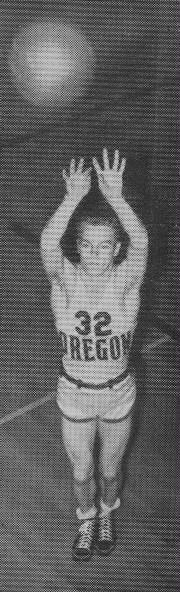

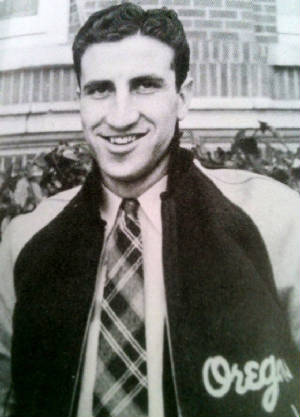

Wally

Johansen

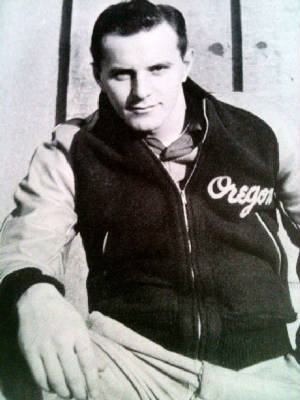

Bobby Anet, the captain and racehorse

pont guard before there were point guards. Laddie and Slim

In the 1930s, the NCAA rules governing recruiting were virtually nonexistent.

It’s also a misconception that coaches didn’t pursue the top prospects and instead just coached whoever showed up. They recruited, recruited hard, and recruited with virtually no restraints. There were scholarships, but they were loosely defined, and the aid often directly drew on the support of athletic department boosters. So that was the system—and a chaotic one at that—as Coach Hobson went after the two boys who would be his senior star big men by 1938–39.

Because his father was an engineer with the Southern Pacific Railroad, Lauren “Laddie” Gale moved around in his youth. Laddie was born in Grants Pass, in southern Oregon, but in his early years, he lived with his father, also Lauren, and mother, Charlotte, in the rural country nearby. His early swimming hole was the Rogue River, near Hellgate Canyon.

Soon, though, his parents were divorced, and Laddie’s father eventually was married five times. Charlotte married another railroad man, Bill Smith, who worked in the Southern Pacific’s Bridge and Building (B&B) department. In the custody of his mother and stepfather, Laddie lived for a while in Portland. His next move, as he was about to enter high school, was to Oakridge, another small town along the McKenzie River about 40 miles east of Eugene. There, he rejoined his engineer father. With a roundhouse for maintenance of locomotives, Oakridge was a Southern Pacific “helper” station at the base of the Cascade Range, on the Cascade Line that went over Willamette Pass. Laddie enjoyed the smalltown life much more than he had Portland, though he occasionally returned to the city to visit his mother. There was no estrangement there. He simply decided he was more suited for Oakridge.

Young Laddie was popular, mischievous, and adventurous, with a terrific barbed sense of humor. That stayed with him for life, and he enjoyed pulling the legs of those who asked about his upbringing in Oakridge, leaving the impression that Laddie had lived in the woods alone or even in a boxcar. There’s no doubt that he was poor during his Oakridge period, as so many were in those Depression years of the early 1930s. His father often was gone with trains, leaving Laddie on his own. It helped that he enjoyed hunting and fishing, and it was for more than sport. But he wasn’t Tarzan in the jungle, either. His son, Hank Gale, chuckles and affectionately says he heard his father tell many tales to others, with variations each time, and that when Hank winced or tried to speak up, Laddie would say good-naturedly, “Shut up, kid.” They were stories spun from the fabric of truth, not falsehoods.

The even smaller town of Westfir was four miles away, and the Number 22 railroad tunnel was between the two. Laddie landed a job cleaning up at the Westfir hall where each week movies were shown on one weeknight and a dinner was held the next. Once, he was cutting through the railroad tunnel when a train came along. He first tried to outrun it, and then jumped to the side and suffered a broken kneecap. (He had scars and visible remnants of wire, used for repairs in those times, to back up his story.) That slowed his high school basketball career, but once he recovered, it kicked into high gear. For a summer, he also worked atop nearby Larison Rock, a forest fire lookout station with a tiny cupola-type house, and he later told Hank—and this one seemed to add up, too—that he sometimes would run into town, three miles away, for a date, and run back to be on the job at the lookout the next morning. A Civilian Conservation Corps camp was in the area, also, and one of the rituals became the CCC men lined up along one wall and the local men lined up along another at the local dances, glaring at each other and competing for the attention of the local girls and women.

In the 1935 Oregon state high school tournament, the Gale-led Oakridge Warriors met the loaded Astoria Fishermen. John Warren and several of his players were impressed with Gale in a losing cause, in part because his one-handed shooting was so accurate and audacious, especially for a kid who, at 6-4, usually was the tallest player on the floor. After joining the Oregon staff, Warren urged his new boss to

go after Gale—and Hobson did it with great enthusiasm.

Gale originally intended to attend Oregon State, but the

coaching changes in Eugene altered the picture and Gale

changed his plans and told Hobson, all right, he would become one of the Webfoots. That left veteran Beavers coach Slats Gill, a former OSC player himself, steaming because it came not long after Hobson also poached the even taller Urgel “Slim” Wintermute, the 6-foot-8 giant.

Wintermute

was born in Portland, but his family had moved to Longview in southwest Washington, and that’s where he played his high school ball. Hobson gave Wintermute’s high school coach, Scott Milligan, considerable credit for being patient with the gangly Wintermute at Longview and nurturing him. At the time, having a big man (or boy) in the middle wasn’t universally valued, especially if a coach favored the sedate game featuring outside set shots. In fact, a big man’s major attraction for some coaches was that he could win so many of the jump balls held after every basket. Many agreed that procedure was stultifying and cheered the rules change before the 1937–38 season. Also, many of the coaches who did appreciate the big men for more than that wanted them to attempt to play the role of goaltender, swatting shots away as they were about to drop into the net.

Slim’s father, a mill worker, was killed in an accident in 1933, and Slim and his mother returned to Portland to live as he was about to head to college. Pencil-thin at 165 pounds, Slim deserved his nickname.

After

Slim indicated he planned to attend Oregon State, Hobson, the

new Oregon coach, didn’t back off. Actually, a coach couldn’t even be sure he had landed a player until the young man showed up on campus, enrolled, and attended classes, so Hobson’s persistence wasn’t surprising or dirty pool. He became more hopeful when Wintermute agreed to visit the Oregon campus in the summer of 1935. Hobson made plans to pick him up and drive him to Eugene, but when the coach arrived at the Wintermutes’ home, he was told that Slim was at a dental appointment. Rather than wait, Hobson went to the dentist’s office—and the first person he saw was Oregon State star football player Frank Ramsey, there to keep watch over Slim. Soon, Slats Gill showed up, too. Gill lectured Hobson that he needed to accept that the young center wanted to go to Oregon State. Hobson said they were friends and both had been Phi Delta Theta men on their respective campuses, but that wasn’t going to save the relationship if Gill prevented Wintermute from visiting the Oregon campus, as planned. Gill said no, insisting he was taking Wintermute to the Oregon State campus for the weekend. When Wintermute emerged from the dentist’s

examination room, he was embarrassed. He rode home with

Gill, but Hobson followed and waited outside. Finally,

Wintermute emerged and told Hobson he had decided to go

to Corvallis for the weekend. But he got in the car and began

a deeper conversation with Hobson, and eventually Wintermute

consented to give Oregon a chance and visit Eugene instead.

He soon said he was going to Oregon.

Hobson estimated that he visited Wintermute seven times more before the center actually enrolled at the U of O, and much of it involved the details of lining up Wintermute’s mother with a place to live and a job at Washburne’s department store in Eugene, plus a part-time job for Slim himself, and then getting them moved to the college town.

* * *

As that summer wound

down, Congress passed, and first-term President Franklin

Roosevelt signed, the Neutrality Act of 1935, banning

the U.S. from trading arms and other military materials with

belligerents in a war. Roosevelt protested that he should have the power to judge which nation was the aggressor and adjust policy accordingly, but when it was clear a bill wouldn’t pass with that kind of provision, he went along. To many, the Neutrality Act was another means to lessen the chances of America being drawn into another European war, and of the men heading off to college—and so many others—someday having to fight in it.

In Corvallis, Slats Gill was determined to make one more run at Wintermute and Gale before the fall term opened. But the Beavers coach couldn’t find the two prospects in Eugene. The savvy Hobson, expecting Gill’s final moves, sent them to a cabin along the McKenzie River and told them to stay there, lay low, and have a good time. Laddie and Slim fished, hiked, boated through the white-water rapids on the river, and talked. By the time they enrolled at Oregon in September, they had forged the foundation of a lifelong friendship. It wouldn’t be, and couldn’t be, as tight as the relationship between Bobby Anet and Wally Johansen, the Astoria Fishermen, but it was significant in the Webfoots’ success. The two big men knew their games and even their personalities were complementary. An entrenched starter, forward Dave Silver, was a year ahead of them, so as they looked around them, they thought about which teammate might be the third member of the startingfront line by the time they were seniors.

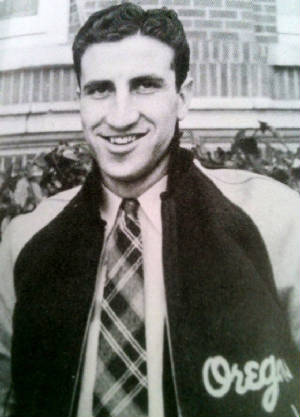

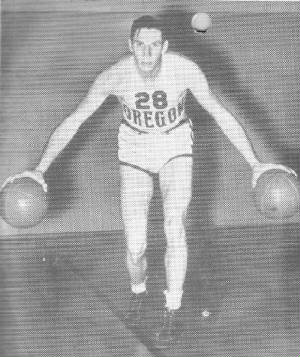

Hall

of Famer Laddie Gale

Slim

Wintermute From the Gorge

John Henry Dick’s

story was quintessential Oregon, and he passed along details

of his family history to his three sons.

His

father, Franklin, was a young, successful chicken farmer in Iowa who became ill and visited a country doctor. He was told: Mr. Dick, sorry to break the news, but you have consumption. You have perhaps six months to live. Facing that diagnosis of tuberculosis with bravery

but determination, Franklin decided to see more of the

world in his time left, sold his chicken farm, visited the East

Coast, and, running low on money, returned home. He visited another doctor for a second opinion, or at least for an update on his timetable and prognosis. The second doctor was incredulous. Consumption? No, what you have, Mr. Dick, is an ulcer. We can fight, and maybe even control, that!

Bolstered by the new diagnosis but determined to get a fresh start, Franklin took the money he had left, jumped on a train, and headed west. Deciding his cash wouldn’t last all the way to the coast, or long in Portland or any other major city, he disembarked in The Dalles, the small farming community at the eastern end of the Columbia River Gorge. Franklin landed a job as a clerk in a local lawyer’s office. Showing an aptitude for the work, he studied and passed the bar examination, becoming a small-town lawyer himself. He married a J.C. Penney seamstress, Louise, and started a family, and John was the second oldest of the four Dick sons, behind big brother Bill. The twist was that because both Astoria and The Dalles were on the south bank of the Columbia, in theory, if young John Dick had dropped a bottle with a message into the river, young Bobby Anet or Wally Johansen eventually might have been able to fish it out as it was about to reach the Pacific.

Dick discussed his upbringing and more in a lengthy interview with Oregon athletic department official Jeff Eberhart for the Order of the O newsletter, distributed to former lettermen.

Only part of the interview ran in the newsletter. Eberhart

graciously passed along an entire transcript.

“Sports and the local trials were the biggest things in town,” Dick told Eberhart. “The entire business district would close an hour before a high school football game and wouldn’t reopen until about an hour after the game had ended. We had 5,500 people in The Dalles at that time and we’d seat about 4,000 to 4,500 people at those high school games.”

When John was a sophomore and big brother Bill was a junior and star of the team, The Dalles High lost a playoff game and the townsfolk were distraught. Bill Dick told his father that his “little” brother, John—already a shade over 6-foot-4 but still a string bean—showed promise but wasn’t yet tough or strong enough. Franklin owned farmland he intended to turn into a wheat ranch. Part of it was still heavily wooded. Every day over the next summer, Franklin

drove John to the farmland, handed him a lunch, and left

him behind to work on clearing the acreage. When The Dalles High School

opened again the next fall, John was beginning to look

a lot more like the powerful forward who played for the Webfoots.

In the next two years, both with Bill as a teammate and after

Bill graduated, John became known as a football star playing end and linebacker.

Howard Hobson and

John Warren recruited Dick for basketball, and they insisted

he could be a college star in the sport if he put his mind

to it. They knew they had a leg up in the recruiting because

Bill was at Oregon, playing both football and baseball. (He

eventually transferred to Willamette University.) John Dick went to the Oregon campus several times to visit his brother and attend games.

“I wanted to

be a student at the university long before I came here,”

John said. “I was also recruited to play baseball and football at Oregon, but you couldn’t play any other sport if football was giving you the scholarship. I chose basketball because I knew we were going to have a pretty good team, and it also gave me the chance to play baseball, which was great because ‘Hobby’ was the baseball coach as well.”

Dick was charismatic and a natural leader, and he was elected the freshman class president. He remained involved in student body politics and spread thin and reluctantly gave up baseball after his freshman year. But his baseball connection allowed him to become friends with former Webfoot infielder Joe Gordon, then in the Yankees’ minor-league system and about to reach the major leagues. The friendship lasted decades.

“Managing my time became an issue, so I chose to concentrate on one sport,” Dick said. “You have to remember that these were the Depression years, so we had to work for our scholarships. Our room, board and tuition were paid for, but we had to buy our own books.”

Dick joined the Sigma Nu fraternity, which had several members from The Dalles and also many athletes, including his eventual basketball teammates Wally Johansen, Bobby Anet, and Ted Sarpola—all from Astoria. Dick made pocket money stocking campus cigarette machines. Despite the lingering effects of the Depression, the good-times mood was prevalent on campus, and Dick unabashedly joined in the partying. The students didn’t have to hide it, either, in the wake of the December 1933 end of Prohibition. As Dick became one of the most-liked men on campus

and a student government leader, his attitude was reflected

in what he later told his own sons: “You can’t

have too few enemies and too many friends.”

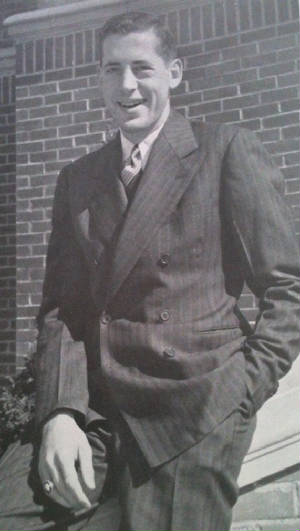

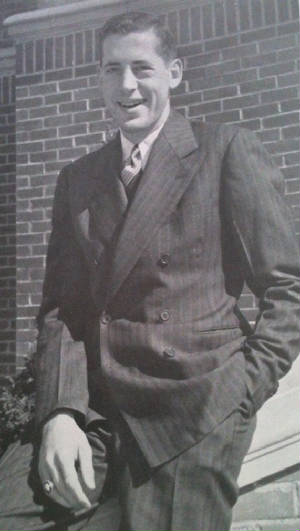

Future captain of

supercarrier USS Saratoga and

future Admiral John Dick, the leading scorer in the first NCAA title game, as the University of Oregon's student body president.

|

|