|

December

7, 2017 Mike Boryla: Ex-Eagles quarterback-turned-playwright, turned-anti-football/NFL crusader

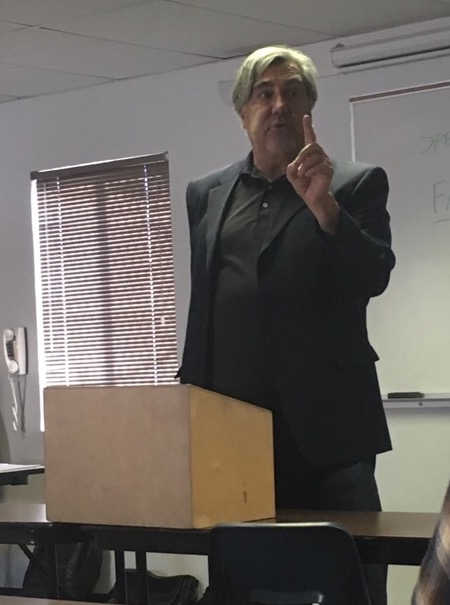

Mike Boryla (Photo

by Taylor Oxenfeld) Former Regis High, Stanford and Philadelphia

Eagles quarterback Mike Boryla is on a crusade. To kill football.

Boryla, who lives in Castle Rock, visited my Journalism 3130 class Thursday at

Metropolitan State University of Denver to tell my students about that ... and a lot more.

Those of us in Boryla's e-mail chain receive frequent fiery missives

about the NFL, citing the scourge of CTE and the league's maneuvering to downplay its impact -- yes, despite the

$1 billion settlement designed to make money available to affected former players. Boryla even has argued that the NFL could

be declared a terrorist organization, shutting it down and subjecting its revenues to confiscation. He told my class

he knew that wasn't going to happen, but he takes that stance to make a point. Boryla talked about the toll he has seen brain injuries take on former

teammates, including with the Eagles and also All-Star Games, as was the case with Mike Webster, the former Steelers

center who died at age 50 after many years of physical and psychological problems. And he also addressed what he

believes is the continued underplaying of studies demonstrating the seriousness of the problem, and the denial of

current players who often seem to believe it can't or won't happen to them.

Boryla recently underwent a first wave of neurological testing as part of the lawsuit,

and his discussions with the medical professionals involved set off bells of recognition. When he was an accomplished

tax attorney for nearly 20 years and was entering his potentially prime years in the climb-the-ladder profession,

he began having cognitive problems and not feeling comfortable with the fine-print legalistic rhetoric so ingrained in

the legal field. He moved into mortgage banking from 2004-11, but even then, he began feeling more creative and

soon he dove enthusiastically into writing.

He believes the creative right side of his brain was taking over. The affected analytic side

of his brain was giving up control. Boryla suffered three significant concussions as a player, one at Regis and two with the Eagles.  Now, at 66,

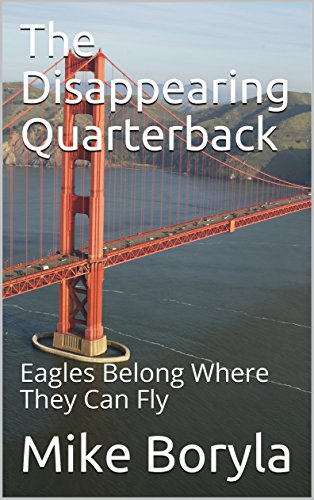

Boryla considers himself a full-time playwright and screenwriter, best known for his one-man play, "The Disappearing

Quarterback," peformed 30 times in

two separate runs at Plays and Players Theatre in Philadelphia and seven times in Denver at the Bug Theatre

and the Denver Center for the Performing Arts' Loft Theatre. After a performance during the

play's second run in Philadelphia, Boryla got word backstage that a man in the audience was asking if he could

meet with the play's star. Boryla agreed, and soon he was having a heart-to-heart with the audience member.

The man explained his name was Bill Musgrave,

he had been raised in Grand Junction, and like Boryla, he also had won the Gold Helmet that goes to Colorado high

school football's top player-scholar.

Musgrave revealed he was the Eagles' quarterback coach.

He also said he had enjoyed the play, and the two men talked about -- among

other things -- the Biblical references and the quarterback craft. The two men haven't yet had a reunion since Musgrave joined the Broncos' staff, but it could

happen at some point.

The play Musgrave and many others have seen and enjoyed opens with Boryla alone on the dark

stage. After 35 seconds of organ music, the audience

hears him calling a play in the Eagles' huddle in 1975. "All right, men," he says, breathing hard, "third-and-7,

we need this! Black right zip ... run pass 37...655 choice. 'Khunya,' watch for the red dog."

Forty-two years ago, that was Boryla's way of asking the Eagles' all-pro tackle, Jerry Sisemore,

to be vigilant on the play-action pass. In the theater, the spotlight then shines on the face of Boryla. And

the plays -- both the football play portrayed and the stage play itself -- take off.

Boryla suffers a concussion on "Black right zip ... "

Then Boryla's script flashes back to earlier

stages of his life, and of his football career. The work is in the tradition of Hal Holbrook playing Mark

Twain or Julie Harris playing Emily Dickinson -- one-character, one-actor plays. Except Mike Boryla plays Mike Boryla.

When Mike was

born, his father, Vince, was playing for the New York Knicks. Vince later spent time as GM of the Knicks, Utah Stars

and the Denver Nuggets, and the family moved to Denver and made it the Boryla base when Mike was in the third grade.

At Regis High, then still in North Denver along with what then was known as Regis College, he took Latin for four

years and loved his coaches, Dick Giarrratano in football and Guy Gibbs in football. Though he won the Gold Helmet in

1968, four years after Bobby Anderson, two years after Freddie Steinmark, and gthree years before Dave Logan, he was a more accomplished basketball player and went to Stanford on a basketball

scholarship.

"I talked them into letting me try out for football," he once told me. "Once I had

my second spring practice in football, the coaches came up to me and said, 'You're not playing basketball any more. You're a football player."

For two years, he backed up Jim Plunkett, who

became and has remained a close friend, marveling at Plunkett's touching shyness despite his prominence as a Heisman Trophy winner. Then he started as a junior and senior and was drafted

in the fourth round by the Bengals in 1974 before his rights were traded to the Eagles.

He started three games as a rookie, mostly backing up Roman Gabriel, and still planning on a short career before going to law school.

That offseason, before he and his

wife, Annie, were married, he lived in his van

in the Bay area.

After the second

of his three seasons with the Eagles, as an injury replacement following the dropping out of Fran Tarkenton and Roger Staubach,

Boryla came on late in the Pro Bowl to replace Jim Hart and threw two touchdown passes to lead the NFC to the win.

Boryla told my

class that he hadn't even expected to play, but Eagles tight end Charle Young went to NFC coach Chuck Knox and insisted on

it. Then, Boryla said, the two TD passes came on the special plays each QB got to install in the NFC playbook -- the

"Boryla Special" and the "Hart Special."

He was traded to Tampa Bay, sat out the entire 1977 season because of injuries, then played

in only one game in 1978 before quitting football for good. He left a lot of money on the table, walking away. He was

banged up and he just wasn't interested.

For years, he scrupulously avoided any media exposure. He cited a passage in Genesis as an instruction to not

look back. But as "The Disappearing Quarterback's" opening approached, he went along with the need for publicity

and did an interview with the Philadelphia Inquirer's Frank Fitzpatrick.

I saw the story and soon reached out to him to do a newspaper story here, too. We've been friends since, meeting for

coffee in shops that have become his preferred

writing venues. He joked with my class that home is too quiet and that he doesn't mind writing kids tripping over him and the voices rising as the caffeine takes effect. His projects are ambitious and varied, including

"The Clone of Jesus of Nazareth," which combines material from three of his plays into a 40-page screenplay treatment; plus the plays "Long Ago and Far

Away" and Ministers of Satan."

On the side, he's taking on football. Here's a YouTube interview with Mike. Among other things, he calls the NFL "psychotic." A couple of my previous Denver Post stories on Mike Boryla: December 8, 2013: The Disappearing Gold Helmet winner July 19, 2015: The Play's the Thing

|