|

Thanks

to the Margaron family -- Patti Bauman Margaron, Matt Margaron and Hana St. Gean -- for their help, cooperation and material. Arlene

Bahr sent this picture to her boyfriend, Marine Bob Baumann, in the Pacific. She's wearing his letter sweater and is at the

Madison firehouse where Baumann lived as a Badger football star.

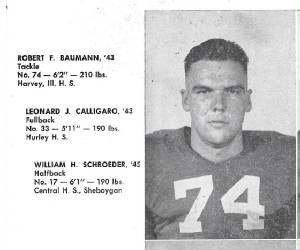

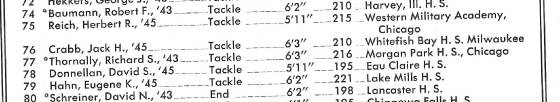

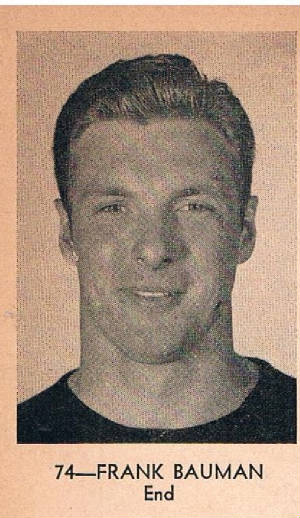

Bob

Baumann is 74, next to teammate and future fellow Marine Dave Schreiner.

Arlene

Chandler was informally engaged to former Wisconsin tackle Bob Baumann -- my father's teammate on the 1942 Helms Foundation

national champion Badgers -- when the Marine first lieutenant was killed in the Battle of Okinawa against the forces of the

Imperial Japanese Army on June 6, 1945. I heard from Arlene in 2006 and was able to get what she told me in several letters

and on the phone in the Third Down and a War to Go paperback. She also sent me several pictures, the actual original prints

of pictures Bob had sent her from the Pacific while serving in the Marines. Bob's handwritten captions were on the back.

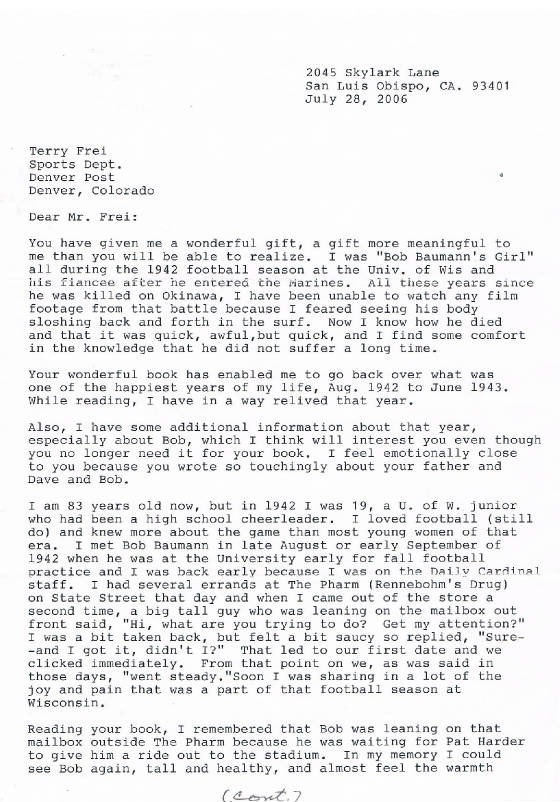

Chandler's first letter,

with a Bucky Badger return address label, arrived from San Luis Obispo, Calif.

She wrote: “You have given me a wonderful gift, a gift more meaningful than you will be able to realize.”

When they met

in early September 1942, Baumann had enlisted in the Marines and was awaiting his call-up. In the meantime, he was getting

ready for the 1942 football season, his senior year for the Badgers. He was waiting for teammate Pat Harder outside

Rennebohm’s Pharmacy when Arlene Bahr, 19, emerged. Arlene realized she had forgotten something and went back into the

store. As she rushed back out, Baumann laughed and asked, “Hey, are you trying to get my attention?”

Years later, Arlene

assured me her response was uncharacteristic. She asked Baumann: “I did, didn’t I?”

Baumann laughed.

Arlene told him about the errands she was running, including mailing some material for the Daily Cardinal, the

student newspaper. Baumann asked if she would join him for a beer that evening after practice. They went to Lohmaier’s

on State Street, where players often gathered for conversation and beers. (The legal drinking age was 18 for beer.)

“We clicked

immediately,” Arlene recalled later. From the 1942 Wisconsin football program.

It's a bit tricky. Bob was "Baumann" at Wisconsin, in everything from class lists to rosters and stories. But his

family at some point had adopted "Bauman," and he seemed to be transitioning to that when he started the enlistment

process with the Marines. As a Marine, he was "Bauman." I decided to make him "Baumann" through the book.

Bob was a child of the Depression in hardscrabble Harvey, Illinois, abutting Chicago's southern border, and he had

been a star and multiple-sport captain at Thornton Township High School. He also did the punting for the Badgers, as a rare

left-footed kicker.

His mom, Bertha, was widowed, and some financial support came from Bob's Aunt Emma. Bob helped

out, working, and at Wisconsin he was always trying to scrape pennies and nickels together for beer money or anything else.

He and Badgers guard George Makris, also a UW boxing team star, later a Marine and then the football coach at Temple, lived

in a Madison firehouse and received a free room for opening and/or closing the big firehouse doors when the fire engine left

or returned. Guards Jerry Frei and Ken Currier had the same arrangement at another firehouse. Baumann was ruggedly

good looking. He wasn't particularly outgoing with his teammates, but he had an undeniable charm and flirtatiousness,

making him popular with women. His teammates sometimes scratched their heads, but not in a jealous sense, but out of admiration.

("How does he do it?") He probably intrigued women, too: Here was a star athlete who played the piano and saxophone.

Some of his teammates joked about signing up for lessons. When weather permitted, Makris took Baumann along on boxing training runs around

Lake Mendota. The boxing team’s student manager was a fat boy named Maury who was jealous of the attention paid

Makris and Baumann, especially by the women on campus. Maury belittled their training regimen as all show and bet

Makris twenty-five dollars that Makris and Baumann couldn’t start from State Street, run all the way around the lake (nearly twenty miles), and make it back

to the starting point without stopping or walking. Before the run, word of the wager got around, and the other Badger football

players got in on the action, backing Baumann and Makris.

The bettors on both sides of the proposition waited on State

Street. Soon, the two big football players, winded but still running, chugged down the street to the designated finish line.

The winning bettors, including most of their teammates, cheered. The losers cursed. Makris’s status as one of the

most popular players on the team was cemented, and Baumann was proud of his buddy and roommate.

By the time the

’42 season started, Arlene Bahr, the Daily Cardinal writer, and Baumann were a couple, “going steady.”

In her letter to me, she noted: "You mentioned that the team often wondered why the girls liked Bob. They thought he

didn't talk. With me, he talked a lot and one of the reasons I liked him was because he was so gentle, kind and, with me,

protective. The team probably saw the aggressive, tenacious football player. I saw the whole man. . . . We walked all over

the city, because we didn’t have a lot of money. He’d never wear gloves, even when it was terribly cold,

because he always said he needed to keep his hands used to the cold so he could hold footballs to punt no matter what

the temperature was. We walked and we talked. I guess you could describe me as a good listener.”" Arlene often

wrote the "Hitting the Badger Beat" gossip column for the Daily Cardinal and Baumann's teammates at first

were curious where the column got its "tips" about the football team, but they soon figured it out and -- not minding

being portrayed as the Casanovas on campus -- went along. One column even noted, "Scene on Campus: Bob Baumann recommending

the Lathrop Library as the ideal place to study anatomy." When the Badgers were sequestered at the local

country club on the Friday nights before home games, Arlene gave Bob a list of her friends and their phone numbers and Bob

suggested that his teammates call them to pass the time. Bob didn't tell them where the numbers came from, but his image as

a ladies' man was enhanced. Arlene joined Bob for the Badgers' post-game gatherings at the Log Cabin or other taverns

on State Street, and she got to know many of the Badgers, most notably George Makris.

Bob was transitioning to "Bauman" in his senior season. (Margaron family.) Badgers coach Harry Stuhldreher was aware what it meant for Badgers from the Chicago

area to play in their hometown, and Baumann was a game co-captain for Wisconsin's wins that season at Soldier Field against

the Great Lakes Naval Training Station and in Evanston against Northwestern.

In the game against Great Lakes,

Baumann went up against Jim Barber, a former star tackle for the University of

San Francisco Dons who outweighed him by about twenty pounds. The stories in the Chicago papers pointed out that Baumann came from the same high school—Thornton Township—as baseball star and Cleveland Indians manager Lou Boudreau.

After the Badgers won 13-7 and scribe Francis Powers in the Sunday Chicago Daily News paper described halfback Elroy

Hirsch as having "crazy legs," Baumann had the game ball on his lap and was taking a nap as the boys chortled about

"Crazylegs" on the train ride back to Madison. Bob unquestionably still had a bit of the quiet

flirt in him.

After the Badgers' big win over Ohio State on Halloween, he encountered a teenaged Badgers fan, Nancy

Schumacher, who had graduated from high school in Mineral Point the previous June.

She put off going to college for a year to work in the Chain Belt plant in Milwaukee,

where she helped make cases for anti-aircraft guns. After the hardback Third

Down and a War to Go: The All-American 1942 Wisconsin Badgers came out in 2004, she also wrote me about Bob.

A star-struck

Nancy kept a scrapbook of the Badgers’ season. After pasting down a newspaper

picture of Dave Schreiner sitting between two coeds, she wrote “PHOOEY”

beneath it.

Her father, Art, was a former UW letterman and thus had tickets on the 50-yard line. Nancy sat in other seats with her mother and planned to join some of her student friends on State Street after the game. But when heavy rains

began, she decided to wait under the stands and was excited to notice some of the

players passing by.

She began asking them for autographs on her program. Bob Baumann smiled and teased Nancy that it would be only fair if she gave him

her autograph, too. Embarrassed at first, she signed. They talked until the rains

let up, and then they went their separate ways, Baumann to meet Arlene Bahr, and

Nancy to hook up with friends. Following the 20-19 win over Northwestern on November 4, Stuhldreher granted Baumann permission to stay behind for

the weekend. After the game, he went to the downtown Chicago train station and met Arlene, and then they took another short

train ride to Harvey to meet his mother, Bertha; his aunt, Emma; and a handful of cousins.

“He hadn’t told

his mother he was bringing me,” Arlene recalled. “When we appeared at the door, his mother was surprised to see

a young woman with her son. He introduced me as his girlfriend, and his family was wonderful.”

And Bob and Arlene were still together when Baumann moved to the Marines, along with

many of his teammates. That came after, at some point in late 1942, Dave Schreiner, Baumann and senior tackle Dick

Thornally drove to Milwaukee to visit the Marine recruiting station. Schreiner apparently was trying to finalize his

enlistment, while Baumann and Thornally underwent physicals.

The three Badgers had borrowed Stuhldreher’s

big green Mercury. They were close to Milwaukee, in the small city of Waukesha,

when a police officer pulled them over and cited Thornally for speeding. In small-town

fashion, the officer took the boys straight to a town building to face a judge.

The judge recognized them and made convivial small talk, telling the three Badger football players—including the All-American Schreiner—that his grandson was on the Wisconsin baseball team. The boys recognized the name.

Sure, they knew him!

“Tell

you what, boys,” the judge said, “you go to Milwaukee and do your business

with the Marines and stop back here on the way home, and we’ll take care

of this!”

On their way back, they stopped in Waukesha and again appeared before the judge.

“He fined me twenty-five bucks!” Thornally told me, his anger undiminished years later. “Twenty-give bucks was a lot! What we had done didn’t seem to have any effect on him.”

As they rode to Madison, Thornally, Baumann, and Schreiner

discussed their future as leathernecks. They were three

of the six '42 Badger seniors -- joining halfback Len Seelinger, plus George Makris and tackle Paul Hirsbrunner -- who finished

up their studies in the spring of '43 and reported to the Marines. The university moved up the academic timetable that spring,

and it was almost as if they simultaneously were handed their diplomas and weapons. On April 8, 1943,

the Bears claimed Baumann in the 24th round of the NFL draft. (There were only 10 teams in the league at the time.) He told

Arlene that he might give pro football a chance—if he ever had the opportunity to do so—to see how it went and

perhaps put together a stake for what he really wanted to do: run a sports camp for children.

In

late 1943, during Baumann’s Marine training, he and Arlene again visited his family in Harvey.

The Baumanns moved

Thanksgiving dinner up to the Sunday before Thanksgiving. On Monday, Arlene, then a senior, returned to Madison for classes,

and Bob followed the next day. “He had a lot of friends he wanted to see, and we went out with them Tuesday and Wednesday

night,” Arlene recalled. “I saw him off on the train on Thanksgiving morning. I can relive that moment, standing

on the platform down at the station, seeing him off. He stood on the step, and he waved goodbye to me.”

Baumann

and Arlene had an “understanding” that stopped short of a formal engagement. Bob gave Arlene his letterman’s sweater and said that would have to suffice until he could afford an engagement ring. And they talked

of marriage, both before he went overseas and in letters as he was posted in the Pacific Theater. "I

loved that 'W' sweater," Arlene told me. Baumann and Dave Schreiner eventually were first lieutenants in the same company --

the Americans' Sixth Marine Division, 4th

Regiment, Company A.

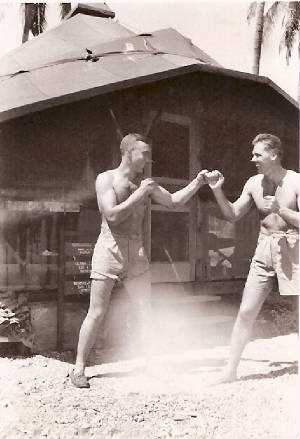

Bob Baumann sent this picture to Arlene Bahr and hand-wrote the caption on the back. Arlene gave me the originals of this and several other photos he sent

her.

After Nancy Schumacher sent Baumann Christmas cards in 1942 and 1943 -- the first when he still was in Madison,

the second sent to his family home in Harvey and forwarded along to him by his mother -- they ended up sporadic pen pals during

his time in the service.

Nancy sent me copies of four letters, and they're clearly platonic in nature.

"I suppose you are a little disappointed with the team

this year but it couldn't be helped with all the boys gone. That was certainly too bad about the QB Shafer. [Badger Allan

Shafer suffered fatal injuries in a 1944 game.] We're still in training out here and and it sure gets tiresome. Sometimes

this heat is unbearable. Every day is over 100 degrees and very stuffy. I sure wish a little Madison weather would come out

this way and I imagine you'd like to have a little of our weather. We had a very nice Xmas and New Year's. Both days, we had

all the fresh turkey we wanted and also had parties both days. I won't go into it any further but you should be able to see

that we had a lot of fun. Well, Nancy, this is all I have time for now so I'll close. Dave S says hello."

By early 1945, Baumann was overjoyed that Arlene had arranged to move to

Chicago. After her own graduation in 1944, she landed a public relations job with the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company

in Akron, Ohio.

There, one of her duties was to write obituaries of former Goodyear employees killed in the war, and,

given where Bob was, that was even more jarring than it otherwise would have been. “It was getting pretty rough

to do that over and over,” she recalled. She was offered a supervisory job with the Akron YWCA, took it, and

successfully applied for a transfer to the downtown Chicago YWCA.

In a March 19, 1945

letter to Arlene from Guadalcanal, Baumann wrote that he liked the fact that Arlene would be closer to her parents in

Wisconsin, so they could watch over her “a bit more.” He continued, “I’m doing it in spirit as

well as I can. I guess you know that, darling. In Chicago, you can visit my mother quite a bit, also, and that will help

things somewhat there. She thinks a lot of you. She said I picked the best there is when I fell in love with you, and

I most certainly agree with her, as I wouldn’t trade you for the world. You officially belong to me.”

He talked of how

he and Arlene would get married after he returned, and that if they couldn’t afford to go anywhere for the honeymoon,

that was OK with him, but that it would be great if they could go to northern Wisconsin and do some fishing on the

trip. “I’m glad you like swimming,” he wrote. “Now I’ll have to teach you to fish.”

When Baumann wrote

that letter, he and Schreiner had less than two weeks left on Guadalcanal. “I could read between the lines,”

Arlene recalled. “They couldn’t exactly say what they were going to do, but he let me know that they

weren’t going to be there much longer. He told me that they’d had a big party that almost tore their tent

to pieces, but that was OK because they weren’t going to be using that tent anymore.”

They moved on

to the Battle of Okinawa. The American Army and Marines landed April 1. The Japanese Army strategy at that point was to wait

and fight elsewhere, not on or near the beaches. The fighting began soon enough.

On April

28, from a military hospital after he was wounded in the early stages of the fighting, Baumann wrote again to Arlene. He said

he had just watched a movie, and that didn’t make him proud. “I’m still at this hospital, laying

around, waiting,” he wrote. “A couple of the boys from my platoon are here, also, so I’m not too lonesome.

I do expect to leave here soon, though, in just a few days.”

He didn’t tell Arlene the specifics of

his wound, either.

“I do miss you terribly, honey,” he added. “You’re the first one I thought of when I was hit.” He returned to his unit, rejoining Schreiner.

On June 21, 1945, Baumann’s

aunt, Emma, called Arlene and said that Baumann had been killed in action.

“No, no, it’s a mistake!”

Arlene cried. She said that officials must have been confused

because Bob had been wounded in April.

“No, it’s no mistake,” Emma said. “The telegram is here.” The Madison headline that afternoon: Bauman, U.W. Tackle in ’42, Killed by Japs

Arlene told me she hadn’t known the details of Baumann’s death until she

read what his fellow Marines told me about it. She always had feared that he had suffered, but the book made it clear he was

killed with a single gunshot to the head. Here's the passage from Third Down and a War to Go that Arlene read about

Baumann's death:

On the third day of the assault, June 6, the Schreiner-led platoon was pinned

down and under heavy fire. Captain [Clint] Eastment was directed to move ahead

with scouts and left Baumann in charge of the company. Years

later (Marine) John McLaughry wrote his memories of what happened next.

He said Baumann’s platoon “was blind-sided by heavy enemy fire from the reverse slope to his left flank. . . . All this time I was in radio contact with Bob who was only some 50 yards away on the reverse side of the ridge.” Sergeant Gus Forbus was with Schreiner. “We were getting the shit kicked out of us, to be honest,” Forbus remembered. “It was really hot, with snipers firing and mortars, you name it. We were in trouble, and we were trying to get

out of there. So Dave and I were evacuating our dead and wounded. We were running;

there’s no walking when you’re under fire like that.” Bodies

littered the trail. Schreiner was used to that, but something clicked in his mind

as he and Forbus ran by one of the many corpses. Schreiner

didn’t stop. “That looked like Bob!” he hollered

to Forbus. “Now, don’t you go back there!”

Forbus responded. With eyes misting, Schreiner kept running.

“We got the ones out we were carrying,” Forbus recalled. “He didn’t

go back. I wouldn’t let him go back.” Later, Schreiner’s

fears were confirmed. The body was Bob Baumann’s. Eastment recalled, “When I came back, they told me Bob had been hit. He got a bullet right through his head.” McLaughry wrote that Baumann “was hit and died as we were discussing [on the radio] how to extricate his platoon.” The irony was that

the day when word of Baumann's death reached his family and Arlene, Schreiner died from wounds suffered the day before in

the final stages of the Battle of Okinawa.

Wisconsin

coach Harry Stuhldreher later received a letter from Len Seelinger, the other ex-Badger who foought on Okinawa with the Marines.

He passed along the gist to Madison reporters. Stuhldreher either read it out loud and the reporters took haphazard notes,

or the Badger coach paraphrased it in different conversations. One Madison paper quoted the letter from Seelinger to Stuhldreher as saying: “Your famous tackle of Harvey,

Ill., will fight no more. The shock of that news really put a lump in my throat.” Stuhldreher also reported

that Seelinger’s letter said Baumann was trying to get to a pinned down Dave Schreiner to tell him that tanks were

on the way.

Another of Baumann’s 1942 teammates, Marine Lieutenant Bob Rennebohm, was in San Diego, preparing

to ship out to the Pacific for the likely invasion of Japan. Before anyone back home told him about Baumann, he found

out another way.

“You won’t believe this,” Rennebohm recalled, still incredulous years later. “I

was standing at a bridge and a camp newspaper came floating down this little stream. I could read the headline at the bottom.”

The headline: “Bob

Bauman, Wisconsin tackle, killed”

Baumann's captain, Frank Kemp, wrote to Bertha, Bob's mother.

The letter was

dated July 20, 1945. "Dear Mrs. Bauman, I have wanted to write long before this, but I received a fairly bad wound in

my right leg on Okinawa and have not been able to do much of anything for a month or so.

My deepest sympathy is extended to you on the loss of your son Robert, When he first came to the battalion. he came

to my old compoany, A Company, and took the 1st Platoon. After the Guam campaign, I considered him the best platoon leader

I had ever seen in action. He was calm in difficult situations never complained or let down when the going was tough, was

always an inspiration to the officers and men of the company...We'll

shall miss him a great deal. I was wounded before Bob was hit. I wish that I could have been with, but one always feels

that one could have helped out.

John Clark was here in this hospital with me but he has been sent to Pearl Harbor.

He writes that he is coming along fine and soon will be back to duty. He took Bob and Dave's loss very hard and they were

inseparable pals. John tells me that Frank [Bob's brother] is now an officer in the Marine Corps. I sure hope the war will

be over before he has to do much fighting. Within a few weeks I am to be sent to the United States for further treatment.

I have quite a bit of hospitalization in front of me.

When I get out I surely hope I shall be able to come

down to Harvey to see you. Sincerely yours, Frank Kemp Capt., USMC"

By the time I was researching Third Down and a War to Go, Kemp was living in Denver.

He repeated those sentiments about Baumann to me and also praised Schreiner.

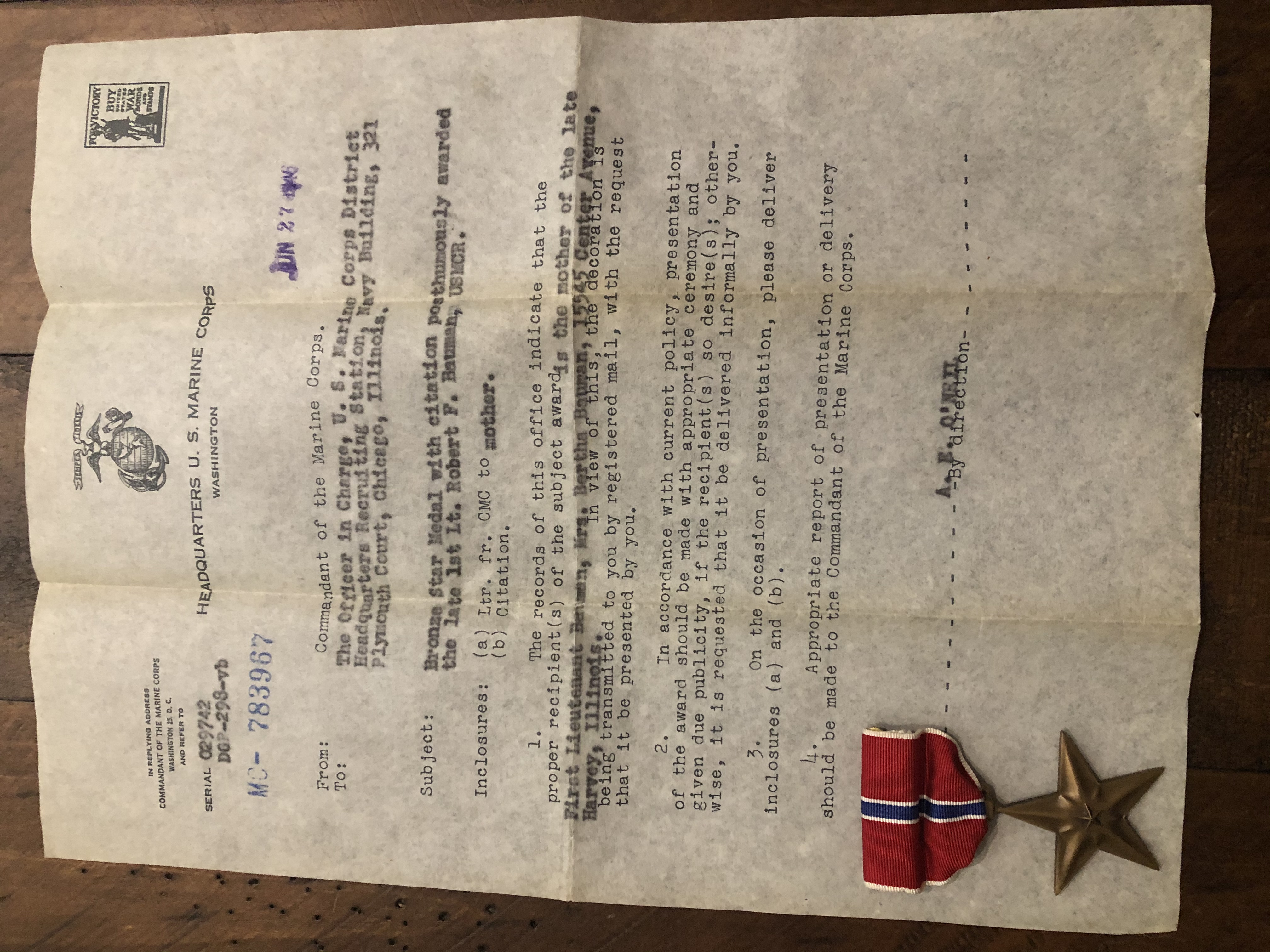

Three weeks after his death, Bob posthumously

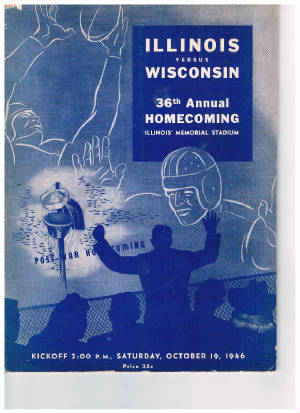

was awarded a Bronze Star. Another irony was that in 1946, Bob's brother, Frank Bauman (one "n"), played for Illinois against many of

Bob's former Wisconsin teammates. My father, Jerry, was among about a dozen Badgers who were sophomores on the '42 team, went

off to serve in the war, and returned to play again in '46 and '47.

Arlene Bahr Vokoun Chandler Arlene never forgot Bob Baumann. At first, she continued in her job as the director

of girls’ activities at the Chicago YMCA. “I put my life back together gradually,” she recalled. She married engineer

Harold Vokoun, a World War II veteran, in 1947.

The couple had two sons, and Arlene stopped working, but Vokoun died of a heart

attack in 1959. Arlene went back to school, receiving a master’s degree from the University of New Mexico and then

becoming the director of student activities and associate dean of women at the University of California–San

Luis Obispo. She married Everett Chandler, a fellow university administrator, and later became a teacher and chair of

the human development department at Cuesta Community College. She retired in 1987 and remained in San Luis Obispo

with her husband.

Bob's Bronze Star and citation, awarded posthumously. (Margaron family.)

POSTSCRIPT In

2021, I heard from Frank Bauman's family -- his daughter (and Bob's niece), Patti Bauman Margaron, and her children, Matt

Margaron and Hana St. Gean. They were terrific. I had been unable to reach Bob's family when researching Third Down and

a War to Go, both originally and then in the second wave for the paperback after communicating with Arlene Chandler.

The one or two "n" issue, plus the Margaron family nme, complicated matters. The Margaron family had a treasure

trove of Bob's belongings and letters and also other material, including his Bronze Star medal and citation and the 1942 Wisconsin-Great

Lake game ball. Some of that is pictured above and I have added other information passed along by the family. I asked the Wisconsin Historical Society Press if it could put out a new paperback

or Kindle edition with the additional Bob Baumann information and updates for all the Badgers and others I had interviewed.

I understood when the WHS said it wasn't possible. The WHS did a terrific job with and showed faith in the project. It also

already had allowed me to do a lot of rewriting and updating for the 2007 paperback edition, including with information from

Arlene. If I ever have a chance, though,

I'd love to do another updated edition.

I did also put author Buzz Bissinger in touch with the Margaron family. Buzz contacted me, letting me know he was

doing a book on the Marines' "Mosquito Bowl" touch football game on Guadalcanal -- focusing on the Marines who played

in it and soon were killed in action on Okinawa. As noted, ex-Badgers Baumann and Dave Schreiner were among them. Buzz hadn't yet been able to find Baumann's family, either. Out of professional courtesy and respect, I agreed to give

Buzz access to my notes and other material, including interview tapes. Most of those I interviewed, including former Marines,

had passed away.

With

permission from the Margaron family, I gave Buzz their contact information.

Buzz's extensively and impresssively researched The Mosquito Bowl, came out

in 2022. Again, here's an omnibus version merging what

I had done on the game for The Denver Post, ESPN.com, my book and my site. Our books were --

and are -- different. The Mosquito Bowl, the game itself, is part of my Third Down and a War to Go narrative

about a college football team's glorious 1942 season in a final-fling atmosphere on campus, then the Badgers' heroic military

service in both the Pacific and Europe. The Mosquito Bowl is both Buzz's focal point and title. For the record, my screenplay for "Third Down and a War to Go" still is out there. From Buzz Bissinger's The Mosquito Bowl:

|