|

July

20, 2024

Fifty-five

years ago, on July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong became the first person to set foot on the moon as part of the Apollo 11 mission

with fellow astronauts Michael Collins Jr. and Buzz Aldrin. The sheer audaciousness of the accomplishment is difficult to sufficiently grasp without considering that only eight

years earlier -- in a May 1961 address to Congress -- President John F. Kennedy had issued the challenge: "I believe

that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning

him safely to Earth." We pulled it off. We could say "we" with pride. Whether the haste and even the goal itself was excessively tied

to Cold War paranoia is a debate for another day. It was a tribute to ingenuity and ambition, and to all involved -- including to the former military pilots who formed

the early astronaut corps. Flash

forward to 1987. I was a (very) young sports columnist

at the Portland Oregonian. Oregon native PGA golfer Peter Jacobsen had come up with a brilliant idea. His company founded the Fred Meyer Challenge,

a non-tour, limited field two-man team event played in Portland on the Monday and Tuesday after The International in Castle

Rock. The first Challenge was in 1986. It eventually ran through 2002. Informally, it was called "Peter's Party." At least in the early

years, it was more fun than a conventional tour event, including because its Monday night banquet between rounds was, well,

quite a party. Jacobsen

and his company also scrambled after The International's cuts to line up players to be in the Sunday pro-am in Portland. (I

have a vague recollection of a Saturday pro-am also being played some years.) There, Jacobsen called in favors, too, and among

the many high-profile figures who came in to play in the pro-am were Jack Lemmon ... and the somewhat mysterious Neil Armstrong

in 1987.

I spent that Sunday

following Armstrong. Here's

my Oregonian column from August 17, 1987. The punchline follows. * * *

After making par on his group's first hole, the man in the floppy yellow hat

walked toward the next tee. Without a long look at the still-recognizable face, it was easy to assume he was one of the amateurs

who paid $2,500 for their Fred Meyer Challenge pro-am spot. Eleven-year-old Amy Donaldson approached with her Disney World souvenir autograph book open. Neil Armstrong smiled and signed. The Beaverton girl -- one of the relatively

few people on the Portland Golf Course grounds Sunday who couldn't vivily remember where she was at 7:56 p.m. PDT on July

20, 1969 -- was breathless with excitement. "He's an explorer-hero," she said of the former astronaut playing in the group with

pro Jay Haas. "I look up to him because he -- oh, how do I put it? -- he was strong enough to go up in something he didn't

know would work or not. "It would be scary to me." We really do remember. Or, like Amy, we care enough to learn. Twelve Americans have walked on the moon. Other footprints have

become smudged, other names and other missions forgotten. Still, when we spot the 57-year-old Armstrong. we quickly flash

back to living black and white. In only eight years, we went from a shell of a space program to sub-orbital flights to 90-minute orbits

with Mercury and Gemini and then to the moon -- and back. But when we see him now, and when "sophisticated" observers

who usually scoff at autograph hounds get out the pen, in a way we are saluting ourselves, Armstrong was right. We all were in on that

"giant leap for mankind." As Armstrong went around the course, the memories were a wave following him from behind the ropes and in the grandstands.

"In 1969..." "Eighteen years ago..." "He was a little skinnier then..." Alan Shepard Jr. hit the golf ball on the moon,

but Armstrong was a good sport when the bantering gallery asked him about the ball's lunar flight. "You can hit it right

over the horizon," he said. Armstrong signed everything thrust at him. Visors. Periscopes. Books. Programs. And the shutters clicked. Lloyd McClintock

of Portland fired away with his Canon. Why focus on Armstrong?

"Because," said McClintock, a Lewis and Clark College law school student, "one hundred

years from now, his name will be the one most famous of those here today. Everyone else will be a question in Trivial Pursuit,

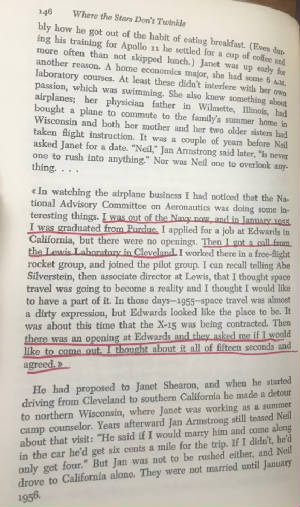

at best." The chosen man was the son

of an auditor for the State of Ohio. Neil moved virtualy every year before settling down near his birthplace during high school.

The closest town was Wapokoneta, Ohio. Neil played football and baseball but was prone to retreat, read, and build model airplanes.

He buillt a wind tunnel in his basement, tseting his planes there and in a nearby park. He worked odd jobs, mostly for 40

cents per hour, to pay for the $9-an-hour flying lessons and obtained his pilot's license on his 16th birthday. After flying 76 combat missions and earning

three air medals in the Korean War, he finished college at Purdue, became a test pilot and then was named the first civililan

astronaut. He was on the Gemini 8 mision before making history with Apollo 11 and Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin Jr., who followed

him down the ladder, and Michael Collins, who circled the moon. In the 18 years since, Armstrong has preferred solitude on his Ohio farm. He

was a professor at the University of Cincinnati from 1971 to 1980 and now is chairman of the board of a company that produces

computer software for corppoate planes. He routinely has turned down interview requests from writers and politely repeated

that policy after his round Sunday. It's understandable, a litle different than an athlete making $1 million beecause

of our preccupation with games, then acting as if talking about a fourth-quarter interception is an invasion of privacy. The

fame of Apollo 11 helped end Aldrin's marriage and drove him to alcoholism. We don't know much about Armstrong. Except we still remember. Dan Wood, a 35-year-old from Lake Oswego,

also approached Armstrong to get an autograph.

"When it happened," he said, "I was at home, watching on televiision with my grandmother.

She was born in 1887 or so, and I thought it was pretty extraordinary that she was watching a man walk on the moon with me." Between the 18th green and

he first tee, 46-year-old Mike Barrett of Lake Oswego stuck out his hand. "Neil, I'd like to shake your hand," he

said. "Good for you."

Armstrong obliged. "He's

an American hero," said Barrett. "I think we're lacking American heroes right now. He embodies what this country

is all about. That's why I went out of my way to shake his hand. "I was watching him on TV in Eugene, and I had tears in my eyes. Sure, I

did. Walter Cronkite was choked up, and so was I. I'm sure we all were."

Me, too. * * *  Postscript:

I would have handled it more directly and personally today, but I had been made aware that Armstrong would not go into the

interview room and most likely would decline an individual interview request after his round. But watching him during the

round, when he engaged with the gallery to a surprising degree, I decided to give it a try. I approached him after he was

done, introduced myself and said I was writing a column about him. I shook his hand and asked if we could talk.

He couldn't have been nicer

in declining. He apologized, but said he just didn't do interviews in this kind of setting, and I took it to mean anything

he did was carefully arranged and selective. (Such as television network interviews.) I wasn't offended. We actually had a

brief and casual chat and I probably could have gotten a couple of quotes from him, even if just about his round and the reaction,

if I'd really pushed. Through

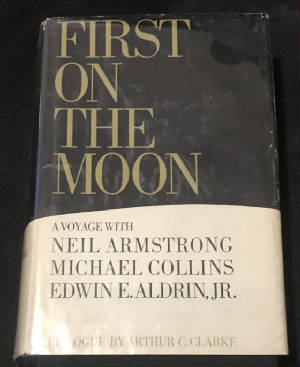

the round, I'd been carrying my copy of the 1970 book, First on the Moon, a quickly issued and quirky mix of

first-person recollection from the astronauts and researched third-person narrative. The title page additionally bills it

as "A Voyage with Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins (and) Edwin E. Aldrin Jr.; written with Gene Farmer and Dora Jane Hamblin;

Epilogue by Arthur C. Clarke." (Clarke wrote 2001: A Space Odyssey and its screenplay

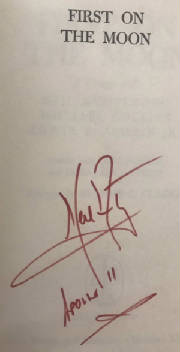

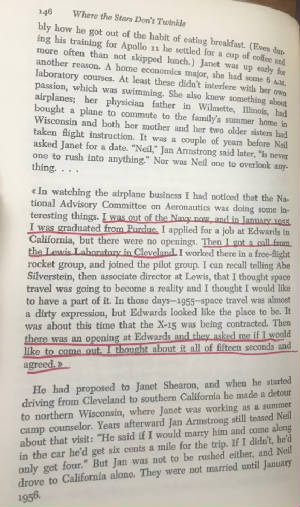

adaptation.) I'd underlined passages in First on the Moon with my red Flair pen about Armstrong's backgound as if

I was cribbing for a final -- or, in this case, for writing a column. (Now that I look at it, some of the underlined information

about his background indeed wound up in the column.) I don't remember exactly how it happened, but I think he noticed the

book, said he didn't see a lot of those anymore, and asked if I wanted him to sign it. Sure, I'd be honored, I said.

Or, then again, maybe I just asked. I do remember handing him the red Flair and him

smiling as he signed. Maybe he looked at it as getting rid of me. So I came away with his autograph -- to the best of my recollection, the only one I ever obtained

directly on the job, as part of a newspaper assignment. This was 33 years ago, before "NO AUTOGRAPHS" was on every

media credential, but I never had chased autographs, anyway. I got one from my childhood sports hero, Willie Mays, when he

briefly was a greeter in Las Vegas and I was there for a fight, and he was at a kiosk, signing casino-supplied cards for free.

I've also got notable signatures on letters tied to book correspondence, and from favorite authors on on their books. This is my favorite. I'm glad I broke my own rule. Armstrong died in 2012. Bob Bell's Mile Hi Property Big Bill's New York Pizza 8243 S. Holly Street Centennial CO 80122 (303)

741-9245 Big Bill's Big Heart JoAnn B. Ficke Cancer Foundation

|