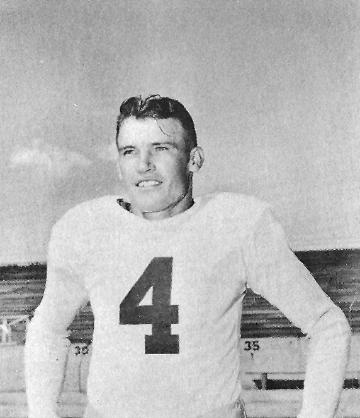

Perry Blach’s family

had been ranching in the Yuma area since his grandfather came over from Austria and homesteaded, building a two-room

sod house in 1887. His father, Ambrose, was born there in 1889. Perry starred in sports for Yuma High School while

participating in 4H and Future Farmers of America activities.

In 1941, Blach went off to A&M. The next year, he was a sophomore lineman, not starting

but getting a lot of playing time, including in the '42 loss to Colorado.

Blach was called up from the Army Reserves in May 1943, but was granted a four-month

extension to help his father farm that summer. After his September induction, he was attached to the newly formed 738th

Field Artillery Battalion. “We had eight-inch howitzers and all the trucks and equipment that went with them,”

Blach told me in his Yuma home. “I was in firing direction. I figured the firing data for those guns.”

Blach went ashore with his unit Normandy’s

Utah Beach about a month after D-Day. “Everything was quiet at that time there, but all the wrecked landing

craft was still in that harbor,” he said.

“We were on a three-quarter ton, what we called a ‘carry-all.’ It was a big pickup and we

pulled a trailer behind that with a lot of our equipment on it.”

On the first night and the next day, the 738th moved 178 miles, much of it under

German shelling. “We ended up in a little town, and by that time, the Allies had so many prisoners, they didn’t

know what to do with them,” Blach said. “Th ey pulled us off the road and gave us barbed wire. We strung

barbed wire and we guarded prisoners for fi ve or six days. You take everything away from them. I still have some

of their pocketknives down in the basement. Then the rear echelon caught up with us and took over the prisoners. They put

us with the 4th Armored, the 80th Infantry and the 35th Infantry, and that was in Patton’s Third Army.”

After about three weeks of rough going, Blach

and his buddies arrived at the Moselle River, near the German border. “Tanks were ahead of us, but if they

ran into something they couldn’t soften up, we’d pull the eight-inch howitzers off and blast ’em and

go on,” Blach said. “My job was to figure the range and the altitude. I enjoyed that part of it because I

always knew where we were, because we had good maps. When we got to the river, we were out of gas and out of ammunition.

If the Germans had known that, they could have walked back across that river and taken all our equipment. We drained the

gasoline out of everything but four trucks to be able to send those trucks back to Paris for supplies.”

After the infantry division was pulled out to

help in the Battle of the Bulge, Blach’s group moved from Luxembourg into Germany and went all the way across

the country, including through Frankfurt, well to the south of Berlin. They were fired upon by artillery and snipers,

and the closest Blach came to getting killed was when he attempted to repair a generator in the open and was subjected

to fire from 88-caliber artillery. At one point, a muddied and fatigued Blach was crossing a road in Germany when he

heard a jeep racing up behind him. He turned and saw stars—three stars on the jeep.

Blach saluted General George S. Patton, and as he passed by, Patton saluted back.

Th e forces moved into Czechoslovakia, where Blach was amused to hear natives ask, “You going to fight the Russkies?”

Then the Germans surrendered. “The Czech people rolled out the beer every night and had big dances to celebrate

and invited the GIs to join them. They made us pull out and turn it over to the Russians, and everybody was sick. We

really felt sorry for them.”

After German occupation duty, Blach was switched to the 945th Field Artillery and had orders to go with that

unit through the Suez Canal to the Pacifi c to join in the war against Japan. “We were still in Germany when they

dropped the first bomb on Japan,” Blach said. “They put us on hold and dropped the second bomb, and the war

ended.”

When Blach was discharged, he

bought the ranch next to his parents’ outside Yuma in 1946 but returned to school and played for the Rams again in

1946 and 1947. “School was easier because I was older and I knew what I wanted,” he said.

Blach served on the CSU alumni board for twenty-four years, became a

major financial booster for the university and the athletic department, and renowned for his Hereford cattle. He and

his wife, Teresa, had nine children.

He

died in 2011.