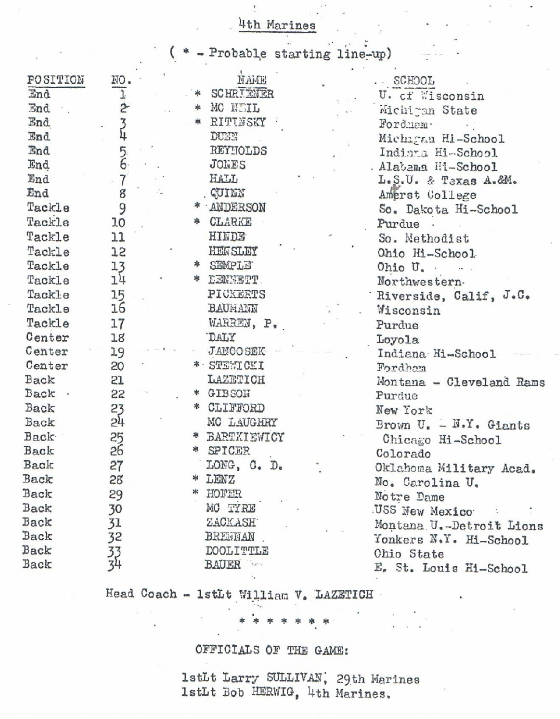

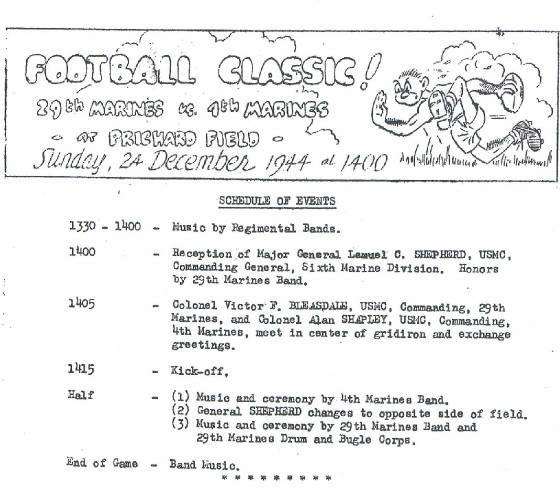

Christmas Eve 1944:

Marines'

Mosquito Bowl

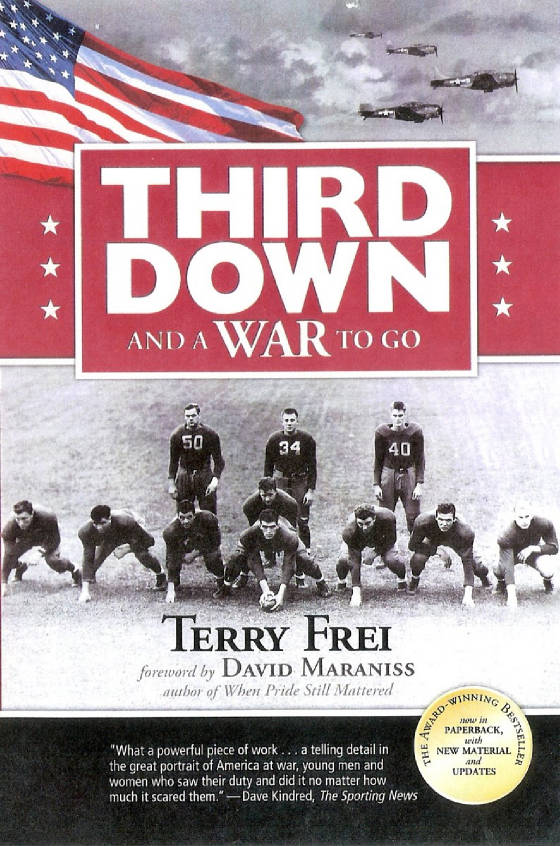

Tentmates

George Murphy of Notre Dame, Dave Mears of Boston University, and

Walter "Bus" Bergman from Denver North High and Colorado A&M/State

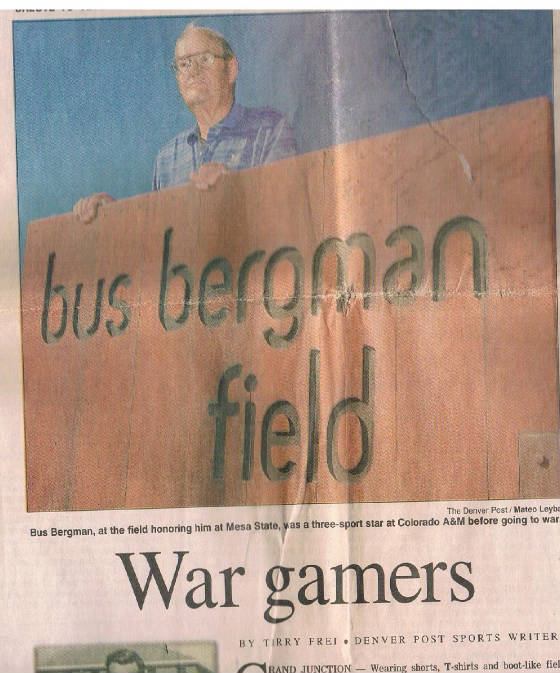

(Denver Post: November 2, 2003)

Prologue

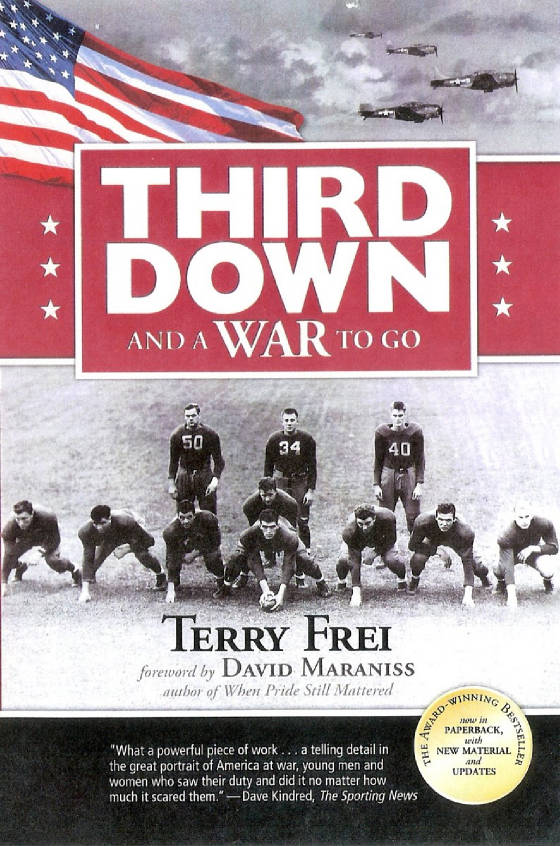

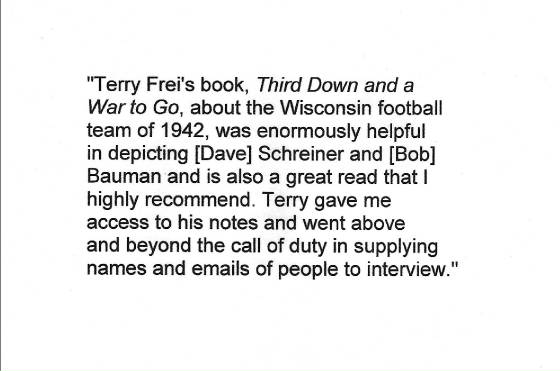

In 2002 and '03, while researching the

book Third Down and a War to Go, about the 1942 Wisconsin Badgers winning

the Helms Foundation national championship in a final-fling campus atmosphere, and then serving with great distinction in

both the European and Pacific theaters, I came across the fact that three members of that team -- Marines Dave Schreiner, Bob Baumann and Bud Seelinger -- all played in

a notable Christmas Eve 1944 touch football game on Guadalcanal.

I also noticed that two other Marines

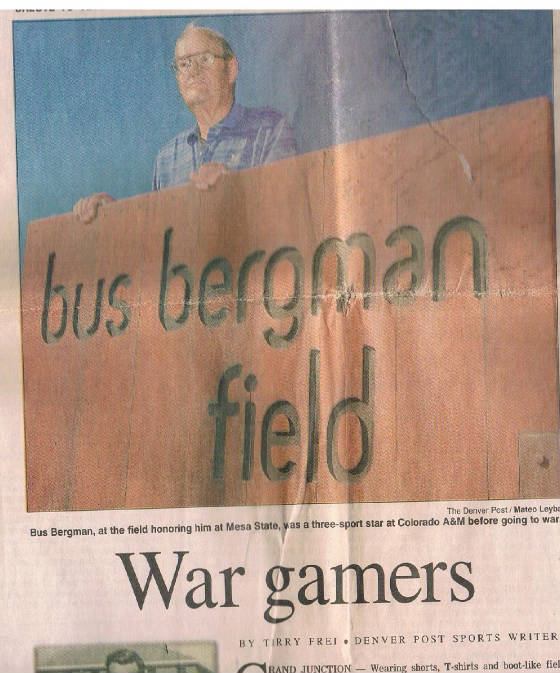

in what was originally billed as the "Football Classic" had played collegiately in Colorado. One was well-known

to me -- long-time Mesa College football and baseball coach Walter "Bus" Bergman, who had been a star at Denver

North High and Colorado A&M. The other was former University of Colorado football and baseball standout Bob Spicer.

I contacted Bergman and Spicer as part of my overlapping research for both a Denver Post

story and the book. In October 2003, I found myself sitting in Bergman's living room in Grand Junction, talking with him for

several hours. He was 83. At the time, his daughter, Jane Norton, was Colorado's lieutenant governor. After that conversation

and the resulting story, I became increasingly fascinated with the Marines' football game -- which came to be known as the

"Mosquito Bowl" -- and the men who played in it and in many cases were killed in action a few months later in the

Battle of Okinawa. One of those was Bergman's tentmate, former Notre Dame star George Murphy. I also knew that ex-Badgers

Schreiner and Baumann died in the fierce fighting, too.

The Post

story ("War Gamers") ran on November 2, 2003. It featured Bergman and Spicer, but touched on others in the wider

tale.

An even more expansive version, this time with the '42 Badgers at the forefront,

was woven into my book -- first in the 2004 hardback, then with additional material added for the 2007

paperback.

I also wrote a 2004 Veterans Day column on it for ESPN.com.

I was able to contact and interview many other veterans of the Sixth Marine Division who served with Schreiner and

Baumann in the Pacific. The Sixth Marine Division Association Directory, listing survivors' units and current contact information,

was invaluable. Schreiner and Baumann both were in the 4th Regiment's Company A. It also became almost a chain communication,

with the Marines providing me with numbers for many not listed in the directory. Unless noted,

any quotes from the Marines in what follows are directly from my interviews or communication with them. They were at least

in their late 70s at the time. It might be best to look at the book's page on this site -- linked above -- for background.

The Denver Post version mostly is the basis of the web site version that follows. I consider

it among the best stories I did in 30 years at the paper. It was one of many examples of my book research leading to offshoot

Post stories. My passion for telling World War II veterans' stories, including my father's, and from both the Pacific and European theaters, was on record. Feedback

confirmed that readers appreciated it, especially as the Greatest

Generation sllpped away from us.

The Story

On Christmas Eve 1944, Bus Bergman and his

fellow Marine lieutenant George Murphy warmed up with the 29th Regiment's team on Guadalcanal, the island in the Solomons

taken by U.S. forces in late 1942.

The tentmates and buddies had been college team captains during their

senior seasons – Murphy in 1942 for the Notre Dame Fighting Irish, Bergman in 1941 for what then were known as the Colorado

Aggies.

Among the military men ringing the field, the frenetic wagering continued. Bergman

and Murphy knew that if the 29th lost to the opposing 4th Regiment, many of their friends would have lighter wallets, or have

to make good on IOUs.

Pressure?

Not compared to what was ahead.

They knew that if they survived the island fighting in the Pacific theater, they would consider themselves fortunate.

For the rest of their lives.

“They say certain guys are heroes because they did this and that,”

Bergman told me. “I say the heroes are those guys who never came back. I’ve thought about that a lot. I think

about the 60 or 70 extra years I got on them. I know I was lucky.”

Bergman for years didn’t volunteer

much information about his combat experiences, even to his children – Judy Black of Washington, Walter Jr. of Grand

Junction and Jane Norton of Englewood, elected Colorado’s lieutenant governor in 2002. His wife, Elinor, also a Denver

native, at times was compelled to point out things Bus neglected to mention.

Little things,

such as the citation that accompanied his Bronze Star.

Raised near the original Elitch Gardens

in northwest Denver, Bergman was a three-sport star at Denver’s North High School. At Colorado A&M, he earned 10

letters in football, basketball and baseball, and also was student body president.

In February

1942, Bergman and Aggies teammate Red Eastlack drove to Denver to enlist in the Marines. The Marines’ preference was

for upperclassmen to stay in college long enough to graduate. To publicize the officer training program, the Marine brass

had the star athletes “sworn in” a second time at midcourt during halftime of an A&M-Wyoming basketball game.

Bergman and Eastlack were playing for the Aggies in Fort Collins, so they toweled off the sweat and raised their right hands.

As he finished his classes, Bergman didn’t respond to an eye-popping $140-a-game contract sent by the Philadelphia

Eagles. After receiving his degree, he went to boot camp and Officer Candidates School, then joined the 29th Regiment at Camp

Lejeune, N.C. By August 1944, he was on Guadalcanal. There, the 29th Regiment became part of the newly formed Sixth Marine

Division.

Bergman, George Murphy and former Boston University tackle Dave Mears were the platoon

leaders in D Company of the 29th Regiment’s 2nd Battalion. The three lieutenants shared a tent, trained and waited.

“We built our own shower at the back of the tent with a 55-gallon drum,” Mears, a retired CPA, told me

from his home in Essex, Mass. “We got a shower head someplace, and we were all set. We were living high!

“Bus was a very easygoing person and very friendly, but when it came to doing his job, he was pretty serious.

George was more serious than either of us, though. At the time, he was married and his wife, Mary, had just had a baby.

So he was further ahead than us that way.”

Murphy showed off pictures to Bergman and Mears of his and Mary Katherine's

newborn daughter, Mary Grace, born in July 1944. Murphy hadn't seen her yet. He hoped he would when ... well, when it was

over.

Looming over the tentmates and all the other Marines was the likelihood

that they were headed for fierce battles ahead. Some already had been in battle before arriving on Guadalcanal, which American

foces had retaken in late 1942.

“We didn’t know where we were going,” Bergman said.

“But we knew it was going to be close to the (Japan) mainland. Football and little things kept us away from all that

talk. Plus, which American forces had we spent a lot of time in that tent censoring the mail.”

He

laughed.

“Marines had girlfriends all over the world, and they wrote to all of ’em,"

he said. "We had to read it, and we were supposed to cut things out, but nobody really said anything we had to worry

about that way.”

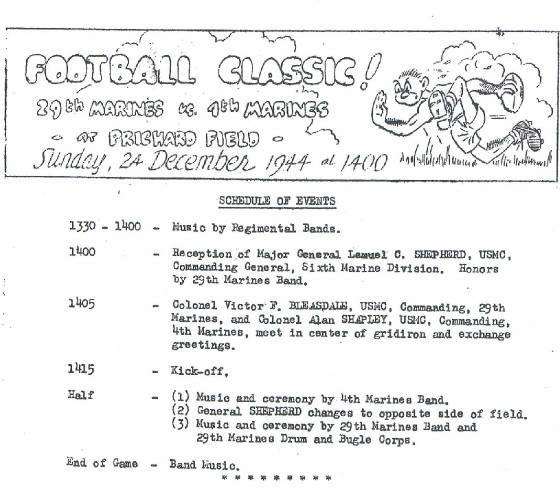

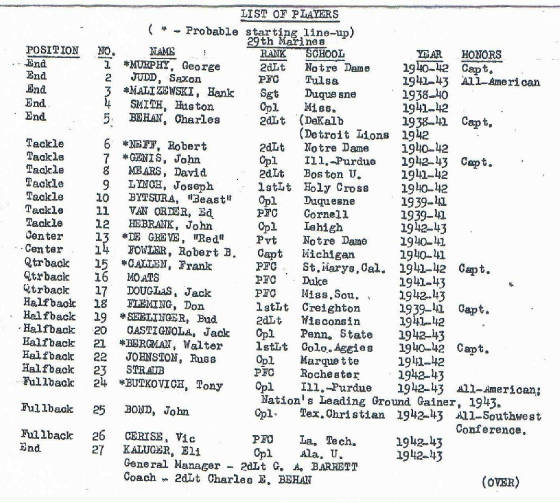

After several pickup games on Guadalcanal, and many beer-fueled debates

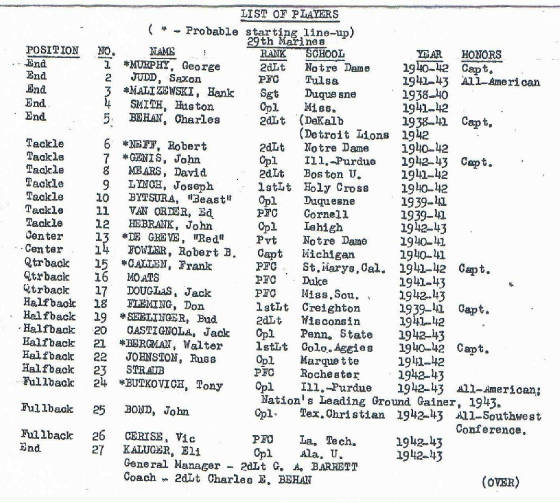

among Marines about which regiment had the best players, the “Football Classic” on Christmas Eve was scheduled.

Organizers mimeographed rosters and lined up a public-address system, radio announcers, regimental bands and volunteer game

officials. The field was the 29th’s parade ground, which had as much coral and gravel fragments as dirt, and no grass.

It was christened Pritchard Field after Cpl. Thomas Pritchard, a member of a demolition squad killed in a demonstration gone

array shortly before the game.

Crowd estimates ranged from 2,500 to 10,000. With no bleachers, Marines

scrambled to stake out vantage points.

Bergman started in the 29th’s backfield,

lining up with former Wisconsin halfback Bud Seelinger; fullback Tony Butkovich, the nation’s leading rusher in 1943

at Purdue and the Cleveland Rams’ No. 1 draft choice in 1944; and quarterback Frank Callen, from St. Mary’s of

California. Murphy was one end and player-coach Chuck Behan, formerly of the Detroit Lions, was the other. Behan captained

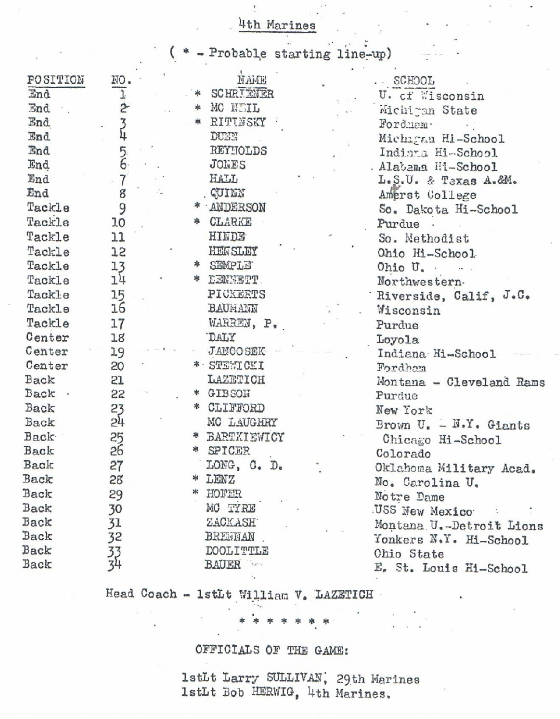

the 29th Regiment squad. The 4th Regiment team captain was Schreiner, Wisconsin's two-time All-American and winner of the Chicago

Tribune’s Silver Football as the Big Ten’s most

valuable player in 1942.

Spicer, who was from Leavenworth, Kansas and had played guard for CU

in 1942, was the 4th Regiment’s starting quarterback.

The game was spirited, violent and inconclusive.

Neither team scored.

Spicer intercepted a pass on the last play of the game.

“It was two hands above the waist,” Spicer said of the rules from his home in Park Ridge, Illinois, “but

it could be a two-handed jab to the shoulder, guts or knees. It was fun!”

Bergman said,

“We hadn’t gotten to practice much, and that’s why it was a 0-0 game, even with all the talent we had.”

John McLaughry, a former Brown University star and ex-New York Giant in the 4th Marines, served as a playing assistant

coach and played next to Spicer in the backfield. He and his 4th Regiment teammates wore light green T-shirts and dungarees,

a better choice than the 29th’s shorts.

“It didn’t get out of hand,” McLaughry told me from

his home in Providence, R.I. “But it came pretty close.”

McLaughry wrote to his parents the day after

the game.

“It was really a Lulu, and as rough hitting and hard playing as I’ve

ever seen,” he said in the letter. “As you may guess, our knees and elbows took an awful beating due

to the rough field with coral stones here and there, even though the 29th did its best to clean them all up. My dungarees

were torn to hell in no time, and by the game’s end my knees and elbows were a bloody mess.”

In the letter, McLaughry said the stars were Schreiner and Bob Herwig, a lineman at California in the mid-1930s.

Bergman said Herwig was best-known among the men for being the husband of Katherine Windsor, author of the controversial,

banned-in-Boston historical novel, “Forever Amber.” Herwig originally was ticketed to be one of the two game officials

and was listed as such on the program. He couldn’t resist playing.

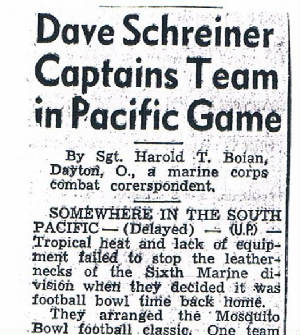

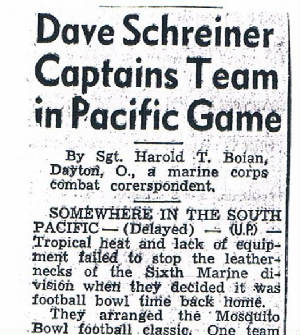

Sgt. Harold T. Boian, a Marine Corps combat

correspondent who later became advertising director for the Denver Post,

wrote a dispatch that was distributed by United Press and ran in many newspapers. Because of wartime secrecy, his story began:

“SOMEWHERE IN THE SOUTH PACIFIC – (Delayed) – (U.P.) – Tropical heat and the lack of equipment

failed to stop the leathernecks of the Sixth Marine division when they decided it was football time back home. They arranged

the Mosquito Bowl football classic.”

Boian listed many of the well-known players in the game. He didn’t

mention Hank Bauer, who spelled Spicer at quarterback, a blocking position in the single wing. Bauer came to the Marines from

East St. Louis (Ill.) High School and would go on to fame as a major-league baseball player, and as a manager.

Survivors don’t remember it being called the “Mosquito Bowl” at the time, and that name wasn’t

used on the program.

Because the game was a tie, all wagers were “pushes.”

Bergman

and the Sixth Division continued training, then left Guadalcanal for Okinawa, in the Ryukyu Islands, about 400 miles south

of Japan.

“I remember that just as we were getting ready to load on our landing craft,

one P-38 (fighter plane) flew over us and I felt like I could reach up and touch it,” Bergman said. “I’ve

never forgotten that.”

Part of a multiservice command operating as a Tenth Army expeditionary

force, the Marines went ashore on the western beaches of Okinawa on Easter, April 1, 1945. The landings were unopposed. The

Japanese forces would make their stands elsewhere.

The 29th Marines first moved up to the northern

end of the island, roughly 65 miles long.

“The only men we lost were from mines and booby traps in caves,”

Bergman said. “We lost our machine gun officer and mortar officer going in one of the caves. But then we came back to

the lower third, and that’s where all the trouble was.”

In the battle for Sugar Loaf Hill, Murphy

and Mears both were hit on May 15.

The Tenth Army’s official Okinawa combat history, published three

years later, said Murphy first ordered “an assault with fixed bayonets” against Japanese forces.

“The Marines reached the top and immediately became involved in a grenade battle with the enemy,” the

combat historians wrote. “Their supply of 350 grenades was soon exhausted.

“Lieutenant

Murphy asked his company commander, Capt. Howard L. Mabie, for permission to withdraw, but Captain Mabie ordered him to hold

the hill at all costs. By now the whole forward slope of Sugar Loaf was alive with gray eddies of smoke from mortar blasts,

and Murphy ordered a withdrawal on his own initiative. Covering the men as they pulled back down the slope, Murphy was killed

by a fragment when he paused to help a wounded Marine.”

A Marine correspondent wrote of Murphy’s

death at the time. That story was carried in many U.S. newspapers in May. It had Murphy making multiple trips to help carry

the wounded to an aid station before he was hit as he rested. It added: “Irish George staggered to his feet, aimed over

the hill and emptied his pistol in the direction of the enemy. Then he fell dead.”

Said

Bergman, “One of the men in his platoon told me he pulled out his pistol and unloaded it.”

In

the battle, 49 of the 60 men in Murphy’s platoon were killed or wounded.

Also on May

15, Mears’ platoon was approaching Sugar Loaf when he felt a flash of pain.

“They

said it was a machine gun, and it was one bullet through my thigh,” Mears said.

Mears was

evacuated to an airfield that night, then flown to Guam the next day, where he heard of Murphy’s death.

“Oh, that one was really bad,” he said. “He was just such a terrific guy. That was a real low blow.”

Mears paused, then added, “But there were so many of them …”

Suddenly,

Bergman was the only tentmate remaining in the battle.

“Then all the outfits got hit

pretty hard,” Bergman said. “Our company went up with others on the 18th and 19th (of May), took the hill, and

stayed there. . . By that last night on Sugar Loaf, I was

the executive officer. I organized a couple of guys to carry ammunition and stuff to different companies up there that night.

We took guys down to the first-aid tent, not so many of the wounded, but several who cracked up from the stress of the whole

deal.”

In the Bronze Star citation, Maj. Gen. Lemuel C. Shepherd Jr. said the

Coloradan “organized carrying parties and supervised the distribution and delivery (of supplies) to all three companies

throughout the night. When time permitted, 1st Lieut. Bergman visited the troops on the line, exposing himself to enemy fire,

speaking to many, reassuring and encouraging them during the enemy’s intense counterattacks.”

U.S.

forces held the hill.

Spicer, the former Colorado player in the 4th Regiment, was wounded

twice on Okinawa. He suffered a shrapnel wound in the arm, but was back in the battle at the end.

“We

were coming north after cleaning up the bottom of the island,” he said. “I jumped over a ditch and found a bunch

of Japanese soldiers lying there. I guess somebody threw a grenade at me. That’s how I lost my eye.”

Spicer said that so matter-of-factly. “That’s how I lost my eye.”

By

July 2, when the campaign was declared over, 15 players in the Football Classic had died on Okinawa.

“It

was just part of the game plan,” Bergman said, shrugging and summoning a sports analogy for war, reversing the usual

practice. “We knew it was going to happen, and it did happen.”

After the island was secure, Bergman visited

Murphy’s grave at the Sixth Marine Division Cemetery.

“It was real tough,” Bergman

recalled softly. He struggled to say something else, then settled for repeating: “It was real tough.”

On that visit, he took a picture of Murphy’s white cross and grave. He still has a tiny print.

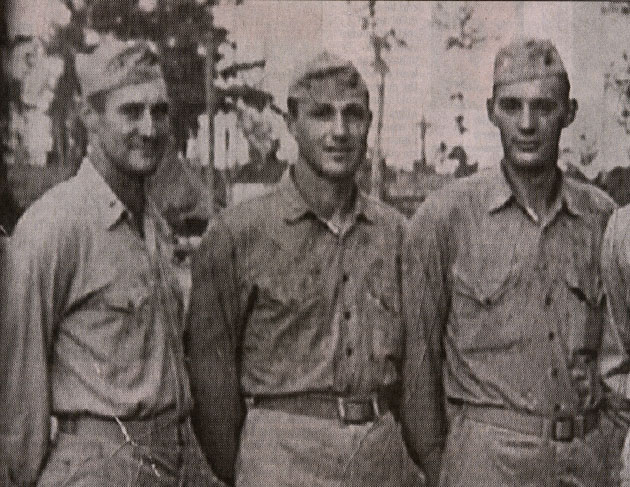

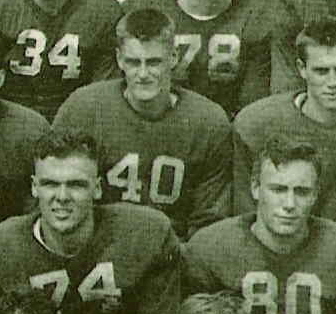

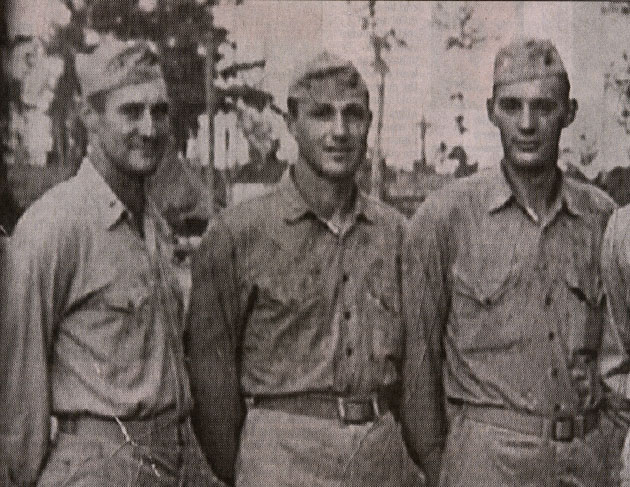

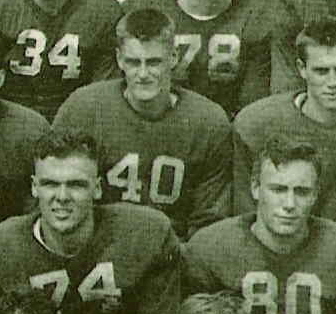

Left: Wisconsin teammates Dave Schreiner and Bob Baumann

as Marines in the Pacific

Theater. Baumann sent this to his

girl/fiancee, Arlene Bahr, with his handwritten note on

the back:

"Junior (Dave) and I putting on a show." They

died 15 days apart in the late stages of the Battle of

Okinawa.

Right:

Baumann (74) and Schreiner (80) in the 1942

Wisconsin team picture. That's Crazylegs Hirsch (40)

behind them.

Like Murphy, the two team captains in the game, Schreiner and

Behan, both died in battle. So did Schreiner's Wisconsin teammate, former tackle Bob Baumann, who served in the same company

as Schreiner.

RELATED: The death of Dave Schreiner

RELATED: The death of Bob Baumann

Behan, born in Crystal Lake, Illinois, also was called both Charlie and Chuck, and he had played end at Northern

Illinois State Teachers College and as a Detroit Lions rookie in 1942 before going into the Marines.

On Okinawa on the the morning of May 18, shrapnel struck Behan in the mouth. Behan's "runner,"

Bill Hulek, wondered if the severely bleeding lieutenant would head back to the aid station.

Behan insisted on staying on

the front lines.

"He kept changing cotton in his mouth," Hulek told me from his home in Castleton, N.Y.

Behan

had a last charge to make.

"We went up Sugar Loaf and got up there all right," Hulek told me.

Behan tossed grenades at a Japanese machine gun nest. Next, Hulek said, "Lieutenant Behan kneeled there with a little

carbine. That jammed, so he took my rifle and started shooting again."

Behan was hit by machine gun fire.

"The bullets came right

out of his back," Hulek said, "and you could see his jacket raised - plink, plink, plink."

Behan posthumously was awarded

the Navy Cross.

In addition to George Murphy, Dave Schreiner, Bob Baumann and Chuck Behan, the other Football

Classic players killed in action were:

– All-American halfback Tony Butkovich,

formerly of Illinois and Purdue..

-- John Henry "Red" Anderson, who had played high school

football in South Dakota.

–Bob Fowler, who attended Michigan.

–Lehigh

tackle John Hebrank.

–Southern Methodist tackle Hubbard Hinde.

–Marquette

halfback Rusty Johnston.

–Wake Forest and Duke halfback Johnny Perry.

–Amherst end Jim Quinn.

–Cornell tackle Ed Van Order.

--

James John Brennan, who had played high school football in Yonkers, N.Y.

-- Don Lee Jones, who had played high

school ball in Alabama.

They were “only” 15 among 2,938 Marines killed or missing in action

on Okinawa. U.S. Army dead and missing numbered 4,675.

Many of the survivors, including Bergman,

were ticketed to serve in an invasion of Japan. Bergman was given a “G-2” summary of the Sixth Marine Division’s

strategy on Okinawa. In the letter on the first page from Maj. Gen. Shepherd, dated Aug. 1, 1945, the Sixth Division’s

commanding officer declared: “I believe that the lessons learned at so dear a price on (Okinawa) should be published

and distributed for the benefit of combat units who will land again on Japanese soil.”

New

President Harry S. Truman approved the use of atomic bombs against Japan, and they were dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki

in early August.

“We were real happy it was going to end the war,” Bergman

said. “Before that, we knew we were going to go to the mainland.”

Instead, the

invasion of Japan was unnecessary after the September surrender, and Bergman’s unit drew occupation duty in China.

Spicer returned to Boulder, lettered three more seasons for the Buffaloes at guard and was the team captain in 1948.

Incredibly, he did it with one eye. After a long career in the banking business, he retired in 1989.

After

the war, Dave Mears returned to Massachusetts and became a CPA. When I spoke with him in 2004, he was 83 and still was cutting

firewood and annually using a season ski pass in New Hampshire.

The daughter

George Murphy never met, Mary Steele, was invited to speak at the Notre Dame Class of 1943's 50th reunion. Murphy posthumously

was honored with the Father Willliam Corby Award, saluting "Honor, Loyalty, and Notre Dame.'" (Mary passed away

in 2000.)

In 1946, Bus Bergman returned to Fort Collins and earned his master’s

degree. He went into coaching at Fort Lewis College in Durango, then moved to Mesa College in Grand Junction in 1950. He coached

the Mesa football and baseball teams, and the baseball team three times was the runner-up in the national junior college tournament

– an event Bergman helped Grand Junction land as the annual host. He retired from coaching in 1974, and from the faculty

in 1980. He was inducted into the Colorado Sports Hall of Fame in 1995.

Bergman told me he often thought about his

Marine buddies.

About those who survived the war. And about those who didn’t.

“They

say certain guys are heroes because they did this and that,” Bergman told me. “I say the heroes are those guys

who never came back. I’ve thought about that a lot. I think about the sixty or seventy extra years I got on them. I

know I was lucky.”

Bergman for years didn’t volunteer much

information about his combat experiences, even to his children—Judy Black of Washington, Walter Jr. of Grand Junction,

and Jane Norton of Englewood, who served as Colorado’s lieutenant governor from 2002 to 2008 and was a Republican candidate

for senator in 2010. During my visit with Bus, his wife, Elinor, also a Denver native, at times was compelled to point out

things Bus neglected to mention. Little things, such as the citation that accompanied his Bronze Star.

On March 25, 2010, Judy Black called me from Grand Junction and left a message, saying Bus was

struggling with congestive heart failure and the family had gathered to say its goodbyes to him. When I called her back, we

talked, and then she handed Bus the phone. I told Bus he was one of my favorites and how proud I was to know him and to have

told his story. I will always treasure his response.

He died three days

later.

Bob Spicer died in April 2006. My Denver Post obit.

Dave Mears died in November 2017.

Postscript

In 2021, I heard from Bob Baumann's

niece, Patti Bauman Margaron, and her children, Matt Margaron and Hana St. Gean. Patti is the daughter of Bob's younger brother,

Frank Bauman, who had played at Illinois and also was a Marine. I had been unable to reach Bob's family when researching Third

Down and a War to Go, both originally and then in the second wave for the paperback after communicating with Bob's college

girlfriend, Arlene Chandler. Different spellings of the last name, plus the current family name of Margaron, complicated

the matter. Bob went by Baumann in all things at Wisconsin -- including programs, roster and newspaper

coverage. He still was listed as Baumann in the Mosquito Bowl program above, but was Bauman in Marine records. The rest of

his family used Bauman. For the sake of consistency, I called him Baumann throughout my book and in the other pieces I've

done about him.

As

it turned out, the Margaron family had a treasure trove of Bob's belongings and letters and also other material, including

his Bronze Star medal and citation and the 1942 Wisconsin-Great Lake game ball. I have added other information passed along

by the family.

I asked the Wisconsin Historical Society Press if it could put out a new paperback or Kindle edition with the additional

Bob Baumann information and updates for all the Badgers and others I had interviewed. I understood when the WHS said it wasn't

possible. The WHS did a terrific job with and showed faith in the project. It also already had allowed me to do a lot of rewriting

and updating for the 2007 paperback edition, including with information from Arlene Chandler.

If I ever have a chance, though, I'd love to do another updated edition. The

screenplay adaptation, written in 2010, is back out there, to

I did put author Buzz Bissinger in touch with the Margaron family. Buzz contacted me, letting me know he was doing

a book on the Mosquito Bowl, focusing on those who played in the game and soon died on Okinawa. Of course, that included ex-Badgers

Dave Schreiner and Bob Baumann. Buzz had seen Third Down and a War to Go. Most of the former Marines and others I

interviewed about Schreiner and Baumann, and for my separate stories on the Mosquito Bowl, had passed away.

Out of professional courtesy and respect,

I agreed to give Buzz access to my notes and other material, including interview tapes. Later, with permission from the Margaron

family after the contacted me, I gave Buzz their contact information.

Our books were -- and are -- different.

The Mosquito Bowl, the game itself, is part of my Third Down and a War to Go narrative about one great college football

team. .

The Mosquito Bowl is Buzz's focal point -- plus his title.

His extensively and impresssively researched book came out in 2022.

Buzz was able to confirm that 15 of the Marines who played in the Mosquito Bowl and were listed in the program died

on Okinawa. The total previously was believed to be 12. I have corrected that here.

From Bissinger's The Mosquito Bowl: